Review: THE YEARS, Almeida Theatre

Nobel prize winner, Annie Ernaux's, semi-autobiographical book is brought to the stage

If you’re anything like me, it’s something to which we have become familiar. You turn your phone on in the morning and there’s a notification saying “Six years ago”. You click on the tab and a photograph is scooped out by the all-seeing eye of Google and there’s yourself or family or friends, familiar yet different. A rush of emotions can flood forward or, maybe, just a shrug of indifference, very occasionally, a pang of pain. What is inescapable is the thought that the photo isn’t just in the phone, it’s also in your soul.

If you’re anything like me, it’s something to which we have become familiar. You turn your phone on in the morning and there’s a notification saying “Six years ago”. You click on the tab and a photograph is scooped out by the all-seeing eye of Google and there’s yourself or family or friends, familiar yet different. A rush of emotions can flood forward or, maybe, just a shrug of indifference, very occasionally, a pang of pain. What is inescapable is the thought that the photo isn’t just in the phone, it’s also in your soul.

The Years' structure plugs into the Proustian rush that old photographs provoke with their momentary elbowing aside of the present in favour of the past. Each of many scenes starts with a recreation of a photo, a snap really, as a toddler becomes a teenager, a girl becomes a woman, a young, struggling writer becomes, well, an old, struggling writer.

The production has been through its own versions of Google’s algorithms - directed by Eline Arbo, adapted as De jaren by Eline Arbo in Amsterdam, made into an English version by Stephanie Bain, based on Les Années by Annie Ernaux - we are informed, somewhat breathlessly, in the programme. The description does leave out the prefix “Nobel Prize winner…” before naming Annie Ernaux, but the writer received that accolade in 2022. Despite all of that filtering, what remains is very French indeed - for better or worse.

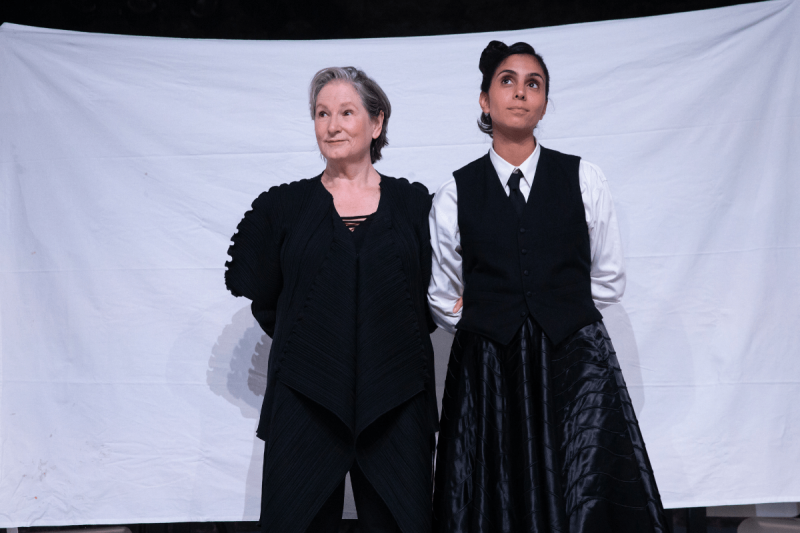

Five actors recount one woman’s story - largely, though not entirely, Ernaux’s herself - telling us much that is personal and much that is universal, and much that is somewhere in-between - female and French. The cast also double for lovers, friends and family, as time passes and a small life expands and then contracts, the way they do.

Harmony Rose-Bremner is the toddler growing up in post-war austerity (she also sings beautifully, Thijs van Vuure’s music a crucial element of the narrative). She hands over to Anjli Mohindra, who plays the teenager who discovers sex and boys in that order. They get most of the laughs with some fine comic exaggerations that seem implausible - until you remember your own kids growing up.

Laughs are far from our minds as Romola Garai portrays the 20-something woman, pitched into the radical movements of the 60s, particularly the emancipation of women and the end of the Algerian war. She is harrowing in her re-enactment of a backstreet abortion, which strongly reminded me of Audrey Diwan’s dazzling and distressing 2021 film Happening, also based on an Earnaux novel. Obviously, this scene will be received differently by each individual in the house and is already attracting some notoriety - a rare case when a trigger warning is not just advisable, but necessary.

Gina McKee covers the divorcee years, the sons, once a burden, now missed, the lover who means too much because he’s always going to walk out sooner or later and the growing stack of journals, full of notes, still refusing to metamorphise into a book. Deborah Findlay gets the elderly years, not without their compensations, but with the sense of an ending always in mind.

The rigidity of the timeline makes everything easy to follow - I think we’ve all had enough of fractured storytelling over the last 20 years or so of cinema. That said, it does lend a somewhat facile element to the narrative, each photo (each ‘year’) introduced with a rehash of the political, cultural and social events underway. Maybe that’s necessary, as this is a Frenchwoman’s history in France, so the rise of Le Pen senior and the declining role of the Catholic church needs teasing out. But it’s a The Rock 'n' Roll Years approach to history lending an unwelcome superficiality to a play that has high culture aspirations ('The Beatles!'). Surely the soundtrack, acting and dialogue would have been enough?

What will certainly divide audiences is how they react to what I might term the “Juliette Binoche” issue. Maybe it’s a peculiarly English reaction (maybe peculiarly an Englishman’s reaction) but so many Binoche films are well made, beautifully acted and attract awards - yet leave many cold. It’s always a middle class life, one insulated from poverty by money and education, one blessed with friends and family and achievement, but also presented as unfulfilled, paralysed by ennui and hobbled by unsatisfactory men. If you heard the Dead Kennedys’ seminal Holiday in Cambodia at an impressionable age, there’s no way that you can avoid a bristling at the self-regard with which we are invited to collaborate.

For those willing to gloss over such thoughts (or simply not accept them as valid) the woman’s story that is all women’s story will shine through across a moving and thought-provoking two hours. And there’s no rule (not outside totalitarian regimes anyway) that says all culture needs to appeal to all audiences or, ipso facto, all reviewers.

The Years at the Almeida Theatre until 31 August

Photo Credits: Ali Wright

Reader Reviews

Videos