Review: RICHARD III, Royal Shakespeare Theatre

Arthur Hughes is compelling as Shakespeare's villainous usurper

The lexicon of the famous opening speech is brutal ("deformed, unfinish'd" - and plenty more) as indeed is the plan Richard announces to clear his path to the Throne. But, usually - if surely soon to become exceptionally - it's spoken by an actor in prosthetics, a man formed and finished.

The lexicon of the famous opening speech is brutal ("deformed, unfinish'd" - and plenty more) as indeed is the plan Richard announces to clear his path to the Throne. But, usually - if surely soon to become exceptionally - it's spoken by an actor in prosthetics, a man formed and finished.

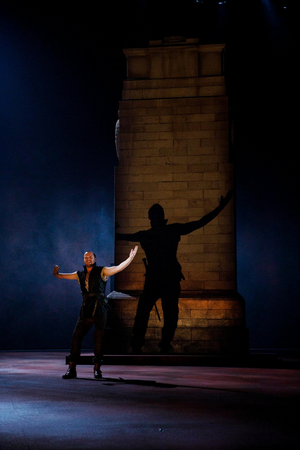

Arthur Hughes, differently-limbed and a magnetic presence, is who he is: no hours in make-up for him, no detailed work with a movement director to get it just right, no inauthentic pity claimed. One feels that those opening words shouldn't be so affecting - the able treating those differently abled as victims first and foremost doesn't sit right either these days - but it's hard to shake the impact of that scene no matter how conspiratorial and conniving Richard becomes. It's a confession with the ring of truth from a man who speaks only for his advantage henceforth.

Gregory Doran is back to direct the final instalment of the RSC's History cycle that began with Richard II in 2012, when, need I remind you, the world was a very different place indeed. This production follows on April's Henry VI: Rebellion and Wars of the Roses (reviewed here) with many of the company (including Hughes) back to play the same roles. We get a lot less noise and gore this time round, with much of the systematic assassination campaign taking place off stage, but it's no less shocking for it.

Three elements emerge most strongly from this Richard - like all great art, it speaks across time and space with different messages from different actors at different times.

For all his considerable slithery charm and that residual sympathy still running strong deep into the three hours plus running time, Hughes' Richard is brimming with misogynistic fervour. Time and again, women are denigrated, blamed, cast aside until, just once, he is left dumbfounded, his infamously successful wooing of Lady Anne (Rosie Sheehy) reversed spectacularly by his sister-in-law, Queen Elizabeth (Kirsty Bushell, superb throughout).

Like much of Shakespeare, Richard III is no thriller, no mysterious whodunnit. We know what's going to happen and, even if we didn't, the characters insist on telling us anyway - no spoiler alerts in Elizabethan times! The pleasure comes (as ever) from the language and the slow unpeeling of psychological states, more revealing of weaknesses than strengths maybe, but all the more fascinating for that ruthless insight the playwright brings to bear on his creations.

Thirdly, and most frighteningly, the cost of complacency in addressing bad statecraft is shown in uncompromising detail. In the face of Richard's ruthless ascent, some are cowards, some are flatterers and some are fools. Only the women are clear-eyed in seeing him for what he is - and they are, of course, ignored. Spectacular ghostly dreams haunt Richard, his victims revenging themselves from beyond the grave and he's too smart not to know that the game is up.

Tudor propaganda it may be - a handsome and benevolent Earl of Richmond, soon to be Henry Tudor, seventh of that name to rule England and Shakey's queen's grandfather - sails in from France to unite the Houses of Lancaster and York. He calms a disquieted country using technology to appeal directly to its people, and humbly honours all its war dead how monarchs have done every Remembrance Sunday for 101 years.

Perhaps a tad wordy (the interval, after 110 minutes gave a welcome chance to stretch the legs and rest the ears) but also a worthy conclusion and timely warning to a country increasingly divided and sorely in need of the statecraft that should never have let Richard, a chancer with an amoral willingness to dissemble, anywhere near the highest office in the land.

Richard III is at The Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford Upon Avon until 8 October

Photo Credit: Ellie Kurttz

Reader Reviews

Videos