Review: RAVENSCOURT, Hampstead Theatre

A striking debut from ex-psychotherapist Georgina Burns, rich with emotional intelligence, clinical precision, and formidable performances.

![]() Mental health services in the U.K. are chronically under-funded. In 2021, 13% of local spend was allocated to them, but the convoluted and astonishingly long process to actively get help means that those who need it often don't even attempt to receive the correct treatment. Research shows that north of four million Londoners struggle with their mental health. It's in this universe - our universe - that Georgina Burns sets Ravenscourt.

Mental health services in the U.K. are chronically under-funded. In 2021, 13% of local spend was allocated to them, but the convoluted and astonishingly long process to actively get help means that those who need it often don't even attempt to receive the correct treatment. Research shows that north of four million Londoners struggle with their mental health. It's in this universe - our universe - that Georgina Burns sets Ravenscourt.

A psychotherapist by trade, her ascent to playwriting started with an unsolicited script sent to Hampstead. While it remained unproduced, the literary manager who suggested Burns to apply for the Theatre's INSPIRE scheme led by Roy Williams. Thus, Ravenscourt was born out of a deep understanding of the subject and a natural penchant for storytelling.

Burns' text is populated by PTSD, postnatal depression, anxiety, and irresistible black humour. Lydia has just moved from private practice to the NHS and has been assigned to the Ravenscourt centre, Denise and Arthur's sinking ship. Burns focuses on Lydia's first case: Daniel is a 33-year-old whose family life is as complicated as his mind is.

He is what they describe as a "revolving door patient", someone who's been in and out of their assistance for years. Arthur and Denise have lost all faith that he will one day come out of it, Lydia believes she can help him. But Daniel's thoughts are more destabilising than he lets on.

Debbie Duru designs a set that looks like a cross-sectioned slice of a building. The talking therapy room owns the space, with its two uncomfortable chairs, drab polyester curtains, stock canvas on the wall, and metal tissue holder. Two corridors book-end it, the staff's offices and where all their exchanges happen. Director Tessa Walker assembles an outrageously talented cast.

Lizzy Watts' Lydia is an appeasing, clever young woman who's slightly patronising at the start. Mostly cool and collected, armed with her emotional support water bottle, she gets on the defensive easily when questioned about her mother. Andrea Hall and Jon Foster are the elder members of the team. She meets his comically lighthearted but always profound ways with clockwork timing as they discuss their patients' mental health issues as a matter of fact.

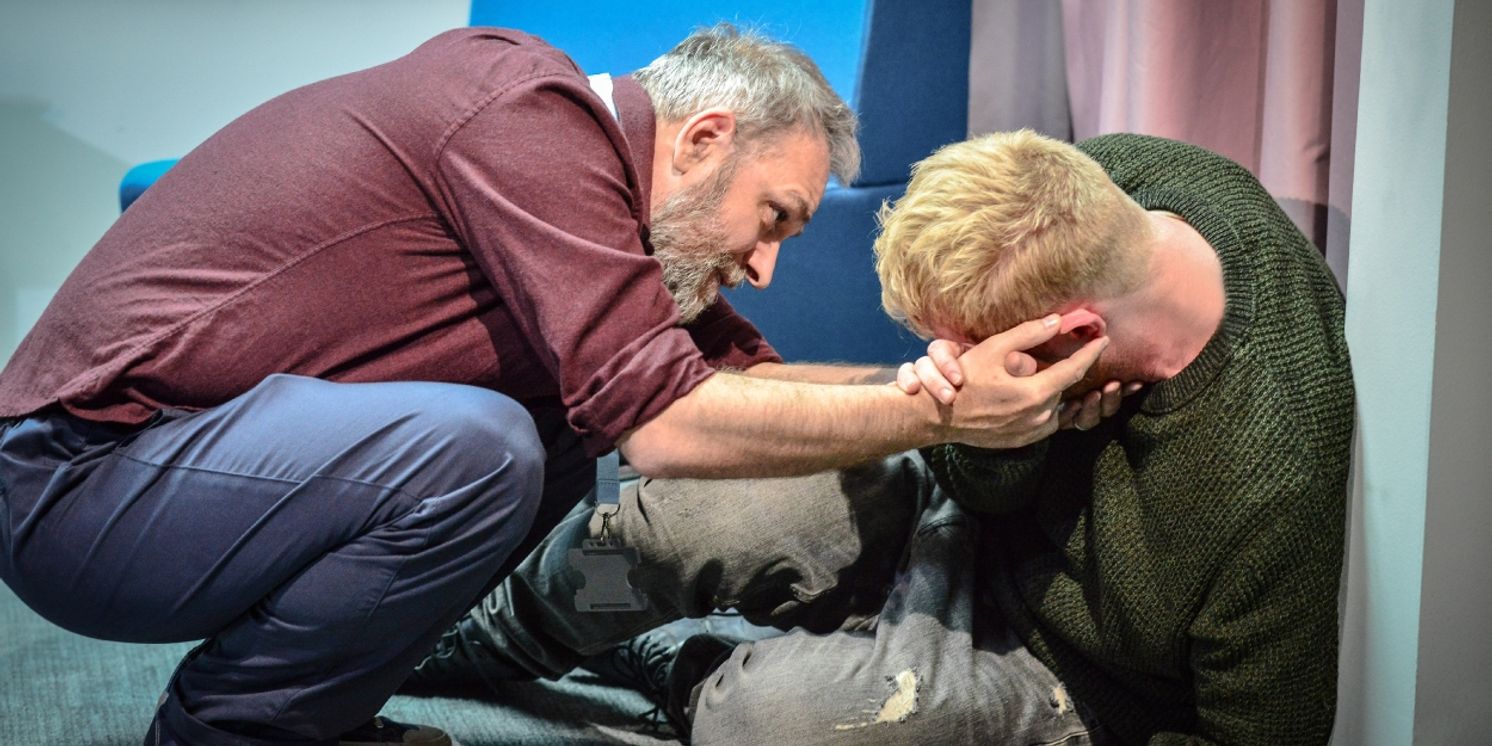

This is the strength of the script. Burns' intent isn't to shock, it's to explain. Arthur and Denise's banter protects them from the personal effects of the horrific context they're in. They don't joke about their nameless patients as a way of disrespecting or vilifying them, their sense of humour simply counteracts the darkness and lightens the play. This duplicity is exquisitely evident with Foster and his own exchanges with Josef Davies' Daniel, whom he shares a particularly jarring, honest scene with midway through.

Davies' formidable performance as a severely depressed man who's been let down by the system over and over again is at the core of the production. He plays Daniel as brilliantly short-tempered, intense and frazzled below the surface of his disillusionment and feelings of dehumanisation. He is a time-bomb that goes off with glaring vulnerability.

Walker's direction is attentive to the details, using subtly expressive body language to establish relationships and cementing the characters' role in each other's space. Scene changes are built on a smooth and unobtrusive choreography that maintains the visual cohesion of the show, making Rebecca Wield (who joins the project as a placement from Central School of Speech and Drama MA program) one to watch.

Narratively, the story isn't anything revolutionary, but Burns' approach is rich with emotional intelligence and clinical precision. She takes on a crumbling, unfeeling practice ruled by waiting lists and scorecards, exploring how destructive the lack of support (financial, yes, but also psychological) can be for those for whom support is a profession. It's a striking, timely debut.

Ravenscourt runs at Hampstead Theatre until 29 October.

Reader Reviews

Videos