Cindy Marcolina

Italian export. Member of the Critics' Circle (Drama). Also a script reader and huge supporter of new work. Twitter: @Cindy_Marcolina

MOST POPULAR ARTICLES

April 25, 2025

The grieving family of a prominent Shakespearean actor gathers at the location where he was due to perform before his sudden demise. The late Henry Elder, however, wasn’t willing to let anything get between him and the celebrations for his career-defining one-man show. Hamlet at the Elsinore Shakespeare Festival (a yearly event that really takes place in the Danish town of Helsingør - aka Elsinore in English) has to go on with or without him. Locked in a hotel room in the middle of the night, the Elders rehearse.

April 23, 2025

All great plays have a moral dilemma buried at the centre. Loyalty, truth, justice, et cetera. The greatest playwrights narrow down these big juicy themes and shape them into a story, making the personal universal and challenging the audience by turning their views against them – it’s a difficult balance to establish. The core of How To Fight Lonelinesshas so much potential. Neil LaBute builds this project around a collection of major arguments, hardly making his characters acknowledge the empirical decisions they face directly. People talk about nothing, saying everything, for over two hours. Assisted suicide, spirituality, lawfulness are the lining of How To Fight Loneliness. Unfortunately, the final product is a redundant show, meaty in its subject but largely exasperating and uninspiring.

April 17, 2025

Victoria Smurfit and Callum Scott Howells are the tragic mother-son duo in an exciting, tense, suspenseful adaptation. Owen shifts the script and makes this classic all about domestic abuse and the power of upper-class disdain. Rachel O’Riordan’s production is a masterclass in distilling tension and concentrating it without frills or games. It’s an emotionally challenging experience, pure theatre.

April 16, 2025

A recently bereaved young man spars with his hyper-critical dead mother and Death himself in an attempt to accept his grief and move on. One too many vignettes à la Scooby Doo chase and not enough personal reckoning have this black comedy twist and turn but never truly fulfil its potential.

April 5, 2025

Following The Audiovisual Media Services Regulation 2014, several acts were banned from explicit content filmed in the United Kingdom. This was done under the radar in a legislative change that resulted in a face-sitting protest in Westminster. The “face-sitters” protested that this bill was, in essence, sexual censorship, an interference in the private lives of an entire nation (the regulations were reviewed in 2019 after a review of obscenity laws). Naomi Westerman takes the incident and makes it the climax of her play. Jaz and Maya fall in love when Jaz joins Maya’s regular dogging group.

April 4, 2025

Sometimes you’re unlucky enough to sit in a room and wonder why plays exist. Jab is an unfortunate example of this. Anne and Don have been married for nearly three decades and they despise each other. She would normally brush his sexist remarks and complacency under the rug, mostly ignoring him during the day as a busy NHS worker, but the nation’s entering the first lockdown. Isolating together, they’re forced to look at their issues.

March 27, 2025

Azuka Oforka’s powerful debut play transports us to the Llanrumney sugar estate in Saint Mary Parish, Jamaica, in 1765, where Elizabeth Morgan (Nia Roberts) lays the law as an unwed modern entrepreneur who’s facing the failure of her crops. All of a sudden, the threat to their survival exacerbates their battle of self-preservation and heart-wrenching compromise. Coming straight from a starry sell-out run at the Sherman Theatre in Cardiff, The Women of Llanrumney is a layered exploration of tyranny and endurance directed by Patricia Logue.

March 18, 2025

Vampires have always had that sexy je ne sais quoi. Whether they have ever been this sexy and this funny at the same time is a different question. Gordon Greenberg and Steve Rosen give Bram Stoker a run for his money with their sensational adaptation of the most famous of blood-suckers. Dracula, A Comedy of Terrors instantly went viral on TikTok when it ran Off-Broadway, ranking up over seven million views for a single snippet of their trailer. This is the lovechild of Mel Brooks and Monty Python, a side-splitting, rib-tickling, neck-biting, hysterically racy show. Charlie Stemp, Dianne Pilkington, Safeena Ladha, and Sebastien Torkia join James Daly, who reprises his role to introduce a pansexual count who’s been alive too long to care about social niceties. You’ll be screaming in laughter.

March 14, 2025

We live in a time where Trump has been accusing the Democratic Party of Communism since his first campaign. He even went as far as describing last year’s election as “a choice between communism and freedom.” But the United States have been on the fear-mongering route for much longer than Trump’s shenanigans began and the transfer of this Untapped Award-winning production is exceptionally timely. Writer and Director Nikhil Vyas introduces us to a real-life event that’s as baffling as this play is striking.

March 11, 2025

Each Thursday night, the most unlikely of groups meet to play Dungeons and Dragons. A struggling teenager, an overworked trainee solicitor, and an unemployed twenty-something become a Dungeon Master, a Wizard, and a Warrior Princess. Instead of fighting the system that lets them down head on, they work together to defeat the Nightmare King. Protected by their spells and weapons, everything seems fine for a few hours. Reality intertwines with their fantasy to unfold a story imbued with grief, where growing up and letting go lie at the end of a gruesome battle with oneself.

March 6, 2025

The production checks off each convention you might think belongs to non-Jamie Lloyd contemporary theatre one after the other. Swanky set? Tick. Random handheld microphone that’s used once? Tick. Eccentric spin on a classic protagonist? Tick. One excellent visual display that re-establishes a recurring allegory? Tick. A strong female character we forget about halfway through? Tick. Live feeds and projections? Tick. That one actor who incorporates BSL in their practice? Tick. Sudden meta-break for no reason at all? Tick. It’s exhausting. It becomes a masterclass in how not to build a new take on Macbeth.

March 1, 2025

Marnie never chose to be a mum. She loves her 4-year-old and would die for him, but he’s not what she expected him to be. When she’s filmed calling him a see-you-next-Tuesday on a plane back from Dubai, the video immediately goes viral. With her lowest moment immortalised for everybody in the world to see and judge, Marnie explores the ambivalence of motherhood. Written and performed by Anna Morris, Son of a Bitch exposes the casualties of virality, unpicking societal expectations to ask an open question: why do we have children?

February 28, 2025

Transferring from a successful run in Bath a few years ago, Oliver Cotton wants to marry politics and art to work his way up to the encounter between an ageing Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederick II of Prussia. The marketing makes it out to be an explosive meeting between church and state, between a god-fearing, scripture-quoting composer and an atheist, belligerent, ruthless monarch. That’s not exactly how it goes and the theatricality of the event is rather underwhelming. Trevor Nunn directs Brian Cox in a lengthy and inconsistent script that swiftly turns into a vehicle for anecdotal politics and bite-size philosophy. Too long into the action, we discover that the catalyst is Bach’s indomitable rage. He found out that a blind young girl was brutally raped by the military and he chooses to hold the king accountable.

February 23, 2025

What do Shakespeare and James Cameron have in common? Before Rupert Goold took hold of the Bard’s tragic masterpiece, the answer would have been ‘nothing’. The soon-to-be artistic director of the Old Vic returns to the Royal Shakespeare Company after 14 years to offer a blockbuster Hamlet. Elsinore becomes a royal battleship and everything happens in less than one night in April 1912. Goold makes some daring choices, placing a lot of faith in his public and letting them interpret and assume certain twists in his vision.

February 22, 2025

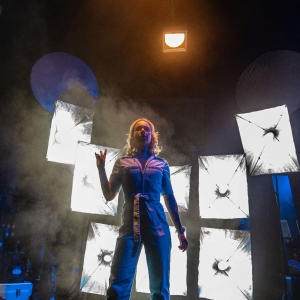

Entertainment is rotten business. Never mind all the allegations against big (normally male) names that regularly appear on our screens, superstardom is a road paved with dubious morals and forced subduedness. From Demi Lovato to Miley Cyrus, from One Direction to Boyzone, regardless of your gender, the industry will chew you up and spit you out.

February 18, 2025

A nation in need, an unsuitable king, banishments, murders, attempted coups. Richard II has it all and so does Jonathan Bailey. He might be dancing through Hollywood and hanging out with the biggest celebs, but he proves that he’s still one of us with this triumphant return to the stage.

February 14, 2025

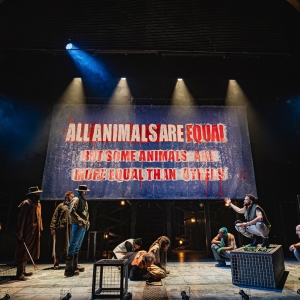

Amy Leach directs Tatty Hennessy’s adaptation of Orwell’s shockingly relevant novella, exploring greed and corruption in a sophisticated production that integrates British Sign Language. It’s essential viewing in the current political climate.

February 13, 2025

The Prozorov sisters are desperate for entertainment. Plagued by their dreary provincial life, they yearn for the lights and excitement of Moscow, but have to make do with the visiting soldiers. When their only brother marries, their sister-in-law isn’t exactly what they dreamed of. Her lacking sense of fashion and initial insecurity builds up to a sharp bossiness upon becoming Mrs Prozorov, leaving Olga, Masha, and Irina at the mercy of the new lady of the house. If you had to choose one work that represented what Chekhov brings to the table, it would be this.

February 7, 2025

The road to the perfect commemorative photograph is anything but smooth with their two unruly personalities. Written by historian playwright John Ransom-Phillips and directed by Bronagh Lagan, Mrs President lives suspended between the lenses of history and fiction.

February 7, 2025

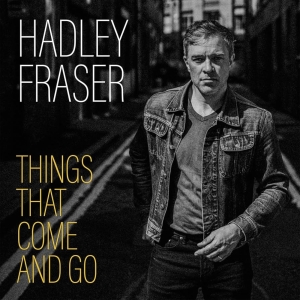

It’s a meticulously organised ten-track album. The songs are famous, but not so excessively that the line-up comes off as a redundant rehashing of standards or a vanity project. The piece has a consistent cohesion to it - sonically but also narratively, with the numbers living inside a bubble of melancholy that cracks your heart open and then lodges into the fracture to heal it.

Videos