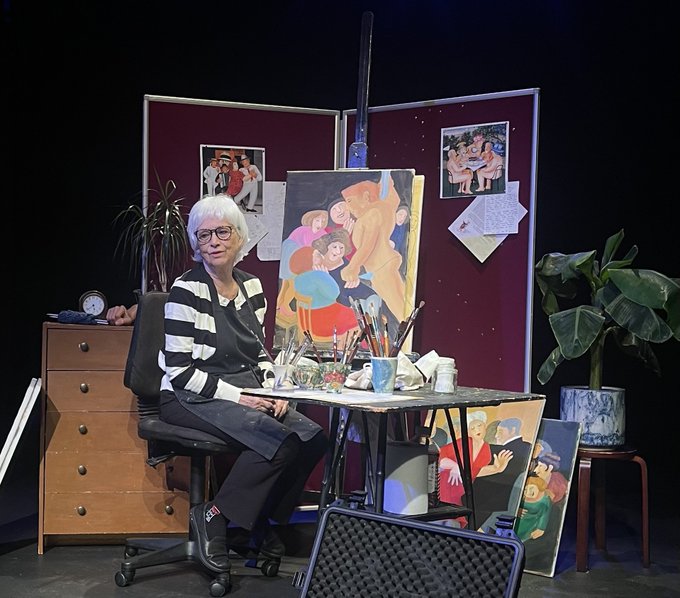

Review: BERYL COOK: A PRIVATE VIEW, Finborough Theatre

Kara Wilson offers an affectionate profile of a much-loved artist

In the days when a branch of Athena adorned (if that’s the right word) every high street, Beryl Cook’s work was everywhere. Her bulky women - nobody used the phrase ‘body positive’ then - were in clip frames on living room walls, on greetings cards and served as a more palatable postcard, if saucy was too spicy. Ironically, the only place you didn’t see Cook’s art was in galleries - most of them anyway.

In the days when a branch of Athena adorned (if that’s the right word) every high street, Beryl Cook’s work was everywhere. Her bulky women - nobody used the phrase ‘body positive’ then - were in clip frames on living room walls, on greetings cards and served as a more palatable postcard, if saucy was too spicy. Ironically, the only place you didn’t see Cook’s art was in galleries - most of them anyway.

Her work fitted into a very British tradition of the playful transgression found in pantos, a smirking (not leering) Benny Hill and in Carry-Ons, with buxom Babs and matronesque Hattie running rings round lascivious Sid and camp Kenny. Of course, humour underpinned the work, but so too warmth, a shared understanding that the ridiculousness of life could not always be smoothed out, that sometimes it just has to be embraced.

Kara Wilson understands this fundamental truth about Cook and about a Britain swiftly now receding in the rear view mirror, which she radiates to the audience. For some it will provoke a Ready Brek Kids warm glow of nostalgia and, for others, an insight into a very different kind of feminism to that of today. Anthropological entertainment at the Finborough!

The framing device is an interview late in life recorded on camera in the early-noughties, when Cook, always private to the point of reclusive, had retreated to her Plymouth home with a few nights out in the more rough and ready pubs her main means of gathering material and socialising. As she paints a typically eye-catching picture of middle-aged women leering at a male stripper (not Magic Mike at the Hippodrome, but Ivor Dickie at The Dolphin), we hear of her life. It’s one in which she and her husband, John, travelled to the beat of their own drum, moving around England, spending time in Rhodesia, eventually settling in the South West. In post-war England, such lives were possible, opportunities continually opening for those with some resources ro call upon, a postive attitude and not much to tie them down.

In her mid-30s, she found her vocation as a painter and, drawing on inspiration from Stanley Spencer and Edward Burra, she just did it for pleasure - as autodidacts do. She was surprised that they sold and even more surprised when one of her paintings appeared on the front cover of the Sunday Times magazine, which let loose a tsunami of interest in her work. Hence Athena, and much else too.

With skill, Wilson (as Cook) recounts this barely believable life with a twinkle in her eye, as she gets her own way with her husband, revels in viewing the regular street brawls in town on a Friday night and displays her postmenopausal, but vital, women so under-represented in art and in life, even today. There are no great insights about The Human Condition, no alternative treatise offered to analyse the History Of Art and, aside from some sweet revenge on an obstreperous neighbour, no scores settled. Like a PG Wodehouse novel, it’s light and frivolous, but it’s also a component in the essential task of maintaining perspective on life - it is, after all, later than you think.

As is the case when viewing the paintings, you leave the show happier than when you arrived. And that’s not a bad place to be.

Beryl Cook: A Private View is at the Finborough Theatre until 26 October

Photo Credits: Finborough Theatre

Reader Reviews

Videos