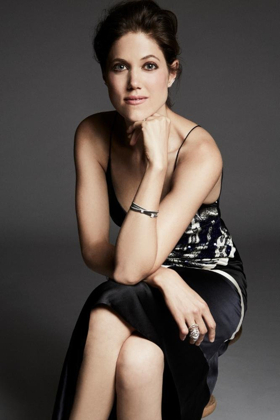

Interview: Charity Wakefield Talks EMILIA at Shakespeare's Globe

Charity Wakefield, currently appearing in Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's all-female Emilia, is the first woman to play William Shakespeare on the Globe stage.

Who is Emilia?

Emilia Bassano, our heroine, was a poet, a contemporary of Shakespeare's, born of Italian descent (her father was in a court band that Henry VIII brought in from Venice as part of his Renaissance "grab"). He was married to an English woman and we think Emilia was born in London.

Emilia was notable for being the long-term mistress of Henry Carey (Lord Chamberlain to Elizabeth I), but she had many lovers. She visited a mystic called Simon Forman, whose detailed notes on London society have been published and provide a source for some of the particulars of her life.

She's most notable for her work - she was a poet, one of the very few women to be published at that time - so she would undoubtedly have known Shakespeare, being so familiar to Henry Carey with his sponsoring of Shakespeare's work. Our play supposes that she is The Dark Lady of Shakespeare's sonnets - a character who appears again and again throughout the sonnets, with varying degrees of lust, possession, detachment and anger directed towards her.

It's also interesting that Emilia is the most commonly used name in Shakespeare's canon. Our play assumes that they did have a relationship and, if that is the case, how might Emilia have affected Shakespeare's writing and how might living in the shadow of so successful a man have affected a woman trying to write and get published at a time when it was nigh on impossible for a woman to do so.

What research did you do on Shakespeare's relationships with women?

I'm fairly familiar with the era, but what was most important to me was to find the real person underneath the known figure. It's been (and continues to be) quite an interesting process of discovery.

One has to use one's imagination, but given the facts that we know, he can't have been a great family man. It's known that his wife and children were pretty illiterate - he didn't bring them into his life in London and he wouldn't have had time to visit them in Stratford.

He probably had many more lovers than Emilia Bassano. Given his work, he must have been out all hours and drank with the last ones left in the tavern. He must have spoken to people from all walks of life and got into the nitty-gritty of their lives in order to write as he did.

I also began to wonder: why the need to write? Why the need to write so eloquently? Why the need to throw yourself into these characters? That began a process of me considering whether the actual person, William, was particularly good at socialising or speaking, whether he felt comfortable in his own skin, whether he would behave differently in public compared to at home.

Did he really hold the beliefs he espoused in his works, or did he bend the truth to be provocative? When you look at modern day characters in very high positions, they're not necessarily as wonderful as they sound in print.

But the character is there to support Emilia's story. The fun of playing at the Globe is that, although everyone knows the character - obviously - which could make it daunting, the audiences are so incredibly friendly and supportive. They've really connected to the play on a much deeper and more visceral level than we could possibly have imagined. The play unleashes something in the people watching - an emotional, hearty, humorous response.

Morgan has structured it very cleverly, managing to make a story about someone who passed away 400 years ago, whom not many people know about, feel very contemporary.

What unique elements are brought to the play by staging it at the Globe?

It was written for that space, commissioned a year ago by Michelle Terry [Artistic Director of the Globe], who has always been fascinated by Emilia Bassano. Morgan really responded to that commission. She's given us the freedom in parts of the play to really use the audience, to speak to them - nor all the time though!

She's created an Elizabethan space, but in a Brechtian way: she starts the play with Clare Perkins stepping on stage and inhabiting the role of Emilia. She says, "I'm Emilia. We are Emilia" to the other two women who'll be playing her at different stages in her life. She also introduces us as muses or actors.

By doing that, she allows the audience to go, "Yes, this is acting, these are storytellers." In terms of an all-female cast working on that stage, where in the distant past it's been completely all-male and predominantly male in the near past, she does a great job structurally there too.

We start with mostly women and, as the women learn to dance, the men are introduced as a big pack. So we arrive (in male costume) in a comic way that the audience can just grab and enjoy, so there's no pressure on any one individual's performance. We all, apart from the women cast as Emilia, play many, many different roles and we all enjoy that process. It's always clear what's happening.

I'm one of the lucky ones who gets to contact the audience directly - I'm playing William Shakespeare and he just would have done! He would have used every trick in the book, and they love that about the character.

Nicole Charles, the director, has allowed us such freedom with bringing in our own ideas and ad libs - we can take opportunities to send things up to the gods - in the way that all Shakespeare's plays do. We're confident with it and the audience enjoy it - and we certainly do.

It's my first time in the main space. I did Othello there with Globe Education 13 or 14 years ago and this play references that one of course - and Othello is in this [Globe] season right now. If anyone comes to more than one show, they'll feel the interconnectedness of the pieces.

Is the specific concept of "The Muse" addressed in the play?

It is - and I would say it is addressed visually and in the text. In one of the scenes, we are "in" the Globe (very meta!) and Shakespeare and Emilia discuss whether she is a muse or not, and Shakespeare, in our play, maintains that she is not a muse. She is a lover, a sparring partner, who challenged him - he used her as an inspiration.

The interesting thing is to explore whether those "muse" relationships are reciprocal, whether they are agreed. What is taken from a muse? And what is received? It makes me think of all manner of artwork - I think of Egon Schiele and the people he may have abused, but the quality of the art is so extraordinary that it seems to surpass that. But what sacrifices were made - and how young those women and boys were, who may have been harmed by that experience.

There's a scene in our play where Shakespeare and Emilia come together after a tragic circumstance that I found really hard to play. I found it difficult to believe that he might be provoking her to speak when she needs his comfort and love, but he is the "war photographer" at that time, the person who can be detached from something horrible because their purpose is to record it.

Many great artists do that and we, as a society, are looking at whether it's worth it. You look at [Harvey] Weinstein, for example, whom I know has denied all the charges against him, but it seems clear to me that something must have happened for all of these people to say what they're saying. And yet he made these incredible films that were so poignant and full of observations about life and seemingly sympathetic to women and the cause of equality.

Though I wouldn't compare Shakespeare to Weinstein on any level really, other than to capture the moment when women - and not just women - who are victims of sexual abuse and manipulation are finding a vehicle for their own words and so gain ownership of their experiences through speaking out. The audience pick up on that with our play at this particular moment - it's a piece of its time.

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm talks about "unlearning" the orthodoxies of writing - did the cast have to do something similar?

This is the most democratic, most collaborative theatre experience I've ever had, including some quite wacky expression at drama school and soon after. That's quite frightening actually - we came to rehearsals with only five weeks before opening, with the play as a structure. The words are stuck to, mainly, but we cut bits (Morgan was with us in rehearsals) and added other stuff.

Under Michelle Terry, the Globe is experimenting quite substantially. We're not using completely the collaborative model she uses in her shows, but we've been encouraged to work out our own way of rehearsing a play. That has been frustrating at times, frightening at times, but ultimately incredibly liberating. I really believe that it has made us shine in our performances because we own it, we inhabit it, in a different way, having created it together, under Nicole's brilliant steering as director.

Even things like the dances and the music, we have made together. The music less so, because Bill Barclay wrote it and wove it into the play - but that has changed substantially through the previews.

To have had such an incredible reaction on the first night was so hearting, emotional and meaningful for us all.

Do you feel the ghost of Joan Littlewood standing in the wings?

Ha! Yes!

How has the industry changed as a result of #MeToo, and where is it going in the next two or three years?

Hmmm. I think more interesting stories will be given support. People now realise that there is a market for stories that don't continue to propagate the same old stereotypes, that white audiences want to see people of colour and that people of colour want their stories told. Also people who are disabled and who are not of society's "norm" respond to being represented by themselves. We will come so far so quickly once that really starts to happen. It feels like there's a big crack that's opened and it's just going to be filled in the next few years.

In terms of working practices, we need to keep the pressure on for things to change. This isn't the first time that women have protested. I work in America as well, so partly my experience and interests lie overseas too. What's happening in politics in the USA is actually causing people to realise that they have to rally to ask for what they want. We need to create systems within workplaces so that people can speak to each other about what may be happening.

I think people need to be held accountable, and part of that is just allowing people to even speak up about what's happened - that's the hardest thing. It's all about finding your voice, which is easy to do watching a film or telly or a play, but it's just so hard to do in your real life on a day-to-day level. So the more we can encourage people to be truthful with one another, the better.

Emilia is at Shakespeare's Globe until 1 September

Photo credit: Alberto Tandoi, Helen Murray

Comments

Videos