Interview: Adam Spreadbury-Maher Talks COMING CLEAN at Trafalgar Studios

Adam Spreadbury-Maher - artistic director of the King's Head Theatre and director of theatre and opera - is transferring his critically acclaimed production of Kevin Elyot's Coming Clean to Trafalgar Studios.

He talks about his career, his approach to direction, and how momentous the play is ahead of its run in January.

Did you go to the theatre a lot as a child?

I did go to theatre a lot a kid - we'd go out to see musicals and plays. I grew up in Cambridge, Australia, which was quite a well-resourced cultural city. I also lived in Sweden, in Gothenburg, when I was 16. I did an exchange year there, so I was able to go to the opera house and to the theatre.

I also travelled around Europe, and before going to university I took a gap year in London as well, so I had a kind of European exposure to theatre, and opera, and musicals, and plays. I trained as an opera singer and went to a conservatoire in Canberra.

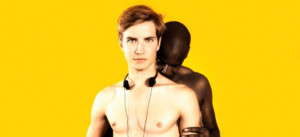

Lee Knight, Elliot Hadley

Where do you see London's theatre standing in regard to Europe?

The main difference to me is that London is, broadly speaking, more interested in the audience understanding everything that's going on, whereas in Europe that's not the primary factor of the theatre-makers.

You were the first to champion unionised pay in unfunded theatres - do you feel we've progressed from 2011?

Oh, yeah! There's hundreds and hundreds of companies and venues that now use the pay agreement.

Do you approach directing opera differently from straight plays?

You know, that's a fantastic question because I do approach them differently, but I also approach them exactly the same in terms of I want the story to be there for the audience.

But making opera is very different from making non-musical theatre. Even the way I make opera is quite different to the way you might find opera made somewhere else. It's a more theatrical form of opera, the drama, the dramatic, the characters, and the storytelling has equal importance to the music.

Usually in opera you only think about all that stuff at the last minute and it's nowhere as important as the music. For me, the form of opera that I make, I want everybody to understand what's going on all the time. Regardless of whether they've been to an opera before or not. It's really important to me.

Do you prefer directing either of the two?

I don't. For me there's no difference. To build the resources, that's slightly different, that's all. You're working with singers who've been to conservatoires versus actors who might have been to drama schools or not. I think I'd get bored if I only did one.

The King's Head is moving more and more into musicals as well, and as a theatre-maker and as an artist, you mustn't stay the same, you must be continually looking and searching and challenging.

I get bored very easily. As an innovator, I'm really interested in looking around the next corner and seeing what's there. That's why I love working in theatre - projects don't last forever, I really like that. But something I give a lot of concentration to is form, I guess. I'm really interested in the future of theatre, especially in studio spaces. It's nice to have a type of long-term trajectory and being OK with moving from project to project.

Is there anything you want to direct but still haven't had the chance to?

Wagner and Shakespeare. I'm not ready yet. And that's a compliment to their work. I probably say a lot of things to make myself feel better about why I'm not doing it at the moment. But I think it will come. With opera, I really like working with the Andrew Lloyd Webbers of the day, if you see what I mean. With plays, I haven't really engaged with anything that was written before World War II.

I think that's got a lot to do with my training in that I was trained by people who were part of the Royal Court in the Sixties, so everything I was given as a young, plastic, impressionable theatre-maker was that tradition. As an artistic director for the past 10 years running venues in London, all my work has either been about either revising work post-war or new work. I think there's room for me to look at it in my future.

What do you think is the greatest accomplishment?

You stumped me with this one. I'm going to give you two answers. At the King's Head I'm really proud that, as a venue, we aren't just about putting on shows and we have a true social and ethical conscience. That kind of began in 2011 with the first pub theatre to have a union agreement.

Since then, we've done a lot of work around looking at how, if there's going to be real change in our industry, it has to happen at its roots. I'm not shaking that responsibility around equality, gender, and pay. So, there's that stuff.

From an artistic perspective, it's really tough. I love all my projects. There's a part of me in everything; there's a very deep, personal part of me in everything that I make. To just look at the last few years, starting with Trainspotting, that's still performing in the UK and Off-Broadway. We did a beautiful La Bohème that transferred to the West End last year and got nominated for an Olivier Award this year.

When you make something in a pub theatre in Islington that's up against the Royal Opera House, it's really something. I'm proud of Coming Clean too. It was potentially going to be lost in history if we hadn't revived it and I'm really glad that we're repositioning it within the British canon.

in Coming Clean

Speaking of Coming Clean, how would you describe it?

It's about a couple who have been living together for five years, 15 years after the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality. Things are settling in a bit but people still get beaten up. Their relationship looks heteronormative from the outside because they're living together, but they still have sex outside the relationship. It seems to be working OK, but then a cleaner arrives and one of them falls in love with him. That's where things come crumbling down.

The play looks at codependency and monogamy; those things have never been more present in an information-overload, attention-span-suffering Instagram world. Codependency and sex addiction are so wrapped in our society and we're just not talking about them. And it's very funny too.

Are you changing anything from your original production?

We've got a new actor playing Greg [half of the main couple]. Since I did Coming Clean initially, I've done a few projects and so have all the actors; we've matured as artists. We're in rehearsals and we're making some changes, but it's more about how we're representing the work in terms of diving into the text a bit deeper.

Why do you think it's important to restage it specifically now?

The play's about change and about how we evolve as people; how we get older and communication is an important part of that. The UK is going through a really huge amount of change at the moment and we're at risk of fracturing as a society. There's a pretty global, serious state-of-the-nation aspect to it.

Also, not just from a homosexual point of view, but from anyone in a relationship point of view, it's all about the idea of talking about codependency, consumerism, and the fact that we're doing what we think Instagram is telling us to do. And are we losing our sense of humour in all that? Or our individual us-ness that makes us who we are, our values? I think that's why the play's so pertinent right now.

What would you like the audience to take from it?

I want them to have a really fun time, because it's really funny. I think it's important to be your you, because there's no point in being someone that you're not.

I love the way that Shakespeare says through Hamlet that we hold a mirror up to our audience and that theatre is a form of therapy and we identify with what's going on on stage. If you can do that whilst entertaining someone, I think that's a really great measure of success.

Coming Clean runs at Trafalgar Studios from 9 January to 2 February, 2019

Comments

Videos