Review: OTSL Stages a Shocking Story in AN AMERICAN SOLDIER

This work has music by Huang Ruo with libretto by David Henry Hwang (of M. Butterfly fame). It is a commissioned expansion of a one-act opera done four years ago in Washington, D.C.

The story is a shocking tale of racial abuse in the military, taken from the headlines of 2011. Danny Chen, born and raised in New York's Chinatown, decided to join the army after high school graduation. He encountered racial abuse ranging from mere teasing to truly vicious verbal attacks. But when he was posted to Afghanistan the abuse became horrendous indeed, to the level of physical assault--even torture. Danny was found dead from a gunshot wound, his death apparently suicide. Several soldiers, including Danny's hateful sergeant, received courts martial, but only light sentences were given out. (The vile sergeant spent thirty days in jail.)

Because of this incident President Obama ordered a ban on all military hazing.

The opera relies heavily on court records. It consists of two acts, with eleven scenes. We jump back and forth in time and space--from the military courtroom to Chinatown, to army training bases, to Kandahar. This gives a rather choppy feeling to the action, and shows that librettist Hwang's Hollywood experience seems to have overpowered his sense of what works on a live stage.

The dialogue (there is never what one might call a lyric) is mundane--even banal--and it's filled with cliché. Occasionally there are violations of lessons learned in Song-writing 101, such as placing a word with an ugly vowel (like "worse" or "girl") on an extended stressed note. (Yes, "'round yon vir-rr-gin" was a mistake.)

The music, on the other hand, is rather amazing. It's not to all tastes, but I found it fascinating. There are, as one might expect, oriental elements that appear occasionally--a phrase or two in the pentatonic scale, say, some parallel fifths. But there are other strange sounds that I'm sure have never before been heard from an orchestra--eerie, haunting, other-worldly, threatening. The opening moment features a soft base drum and a digeridoo; later, whirly-tubes sing mysteriously. There is much strident dissonance, as befits the violent actions and emotions on stage. For the most part the singers are left to themselves while the orchestra busily machinates beneath them.

The role of Danny is sung by tenor Andrew Stenson, who sang the role in the one-act version four years ago. His is a beautifully clear, pure, powerful voice--smooth across the entire large range the role requires. And he is a wonderfully committed actor.

Mezzo Mika Shigematsu does excellent work as Danny's mother, fully embracing the heartbreak of this mourning woman who will not believe that her son killed himself.

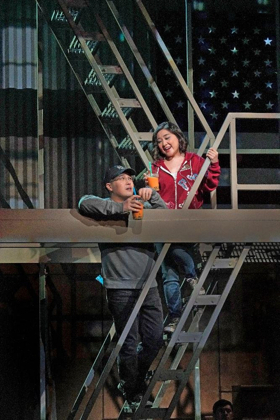

Danny's high-school friend Josephine is not a character in the real-life story, but was added to the opera to gain another female voice in the mostly-male cast. Good choice! Kathleen Kim brings bright life to her scenes, freshening the whole production.

The almost-love duet between Danny in Afghanistan and Josephine in Chinatown is the most beautiful scene among many rather disturbing ones. A lovely touch is the presence of two moons in their two, so terribly separated skies.

Bass Nathan Stark sings the military judge--a rather thankless role consisting of calling one witness after another. But he has another chance to shine: he leads the "E Pluribus Unum" number--the "finale" if you will--and he does it richly and beautifully.

The villain of the piece, Sgt. Marcum, is sung by bass-baritone Wayne Tigges. He does it with power and commitment, but I do hope his mother washes his mouth out with soap after each performance. Poor Mr. Tigges, in his abuse of his platoon, is burdened with the most vile and offensive language I've ever heard in an opera.

Herein lies the key to the failings of this work. The librettist does everything he can to make Sgt. Marcum utterly, marrow-deep evil. He's not even a psychopath--he's a cartoon of one. As such he is incapable of driving dramatic action. In a tragedy the protagonist drives the action--to his own destruction. In melodrama the villain drives the action. (Much classical opera is indeed melodrama.) But An American Soldier--certainly no tragedy--fails even as melodrama, because the bad guy has no motivation; he's just not interesting--he's simply bad. Dramatically speaking poor Danny might as well have been killed by a bolt of lightning.

And now that finale. After the trial and the painfully inadequate sentence the stage fills with a military chorus. The judge, in officer's uniform, leads the group in almost a hymn to the nation's motto--E Pluribus Unum. That's a terrific motto. Last week in Philadelphia, at the Museum of the Revolution, I was almost moved to tears watching a group of school-children drinking in the discussion and the many illustrations of that motto. But in this opera the E Pluribus Unum number, though musically quite beautiful, is filled with such shallow, clichéd flag-waving patriotism that it's hard to take seriously. It closes with a long, long list of every conceivable minority that has ever been denied sufficient respect--ending, of course, with "LGBT"--all now lovingly embraced in that glorious motto. All in all it is more than a little maudlin.

In the final moment Danny's mother, holding his memorial flag, reprises a lullaby which she sang at the top of the show. It's an obvious, but nevertheless effective device.

So, An American Soldier at Opera Theatre St. Louis has beautiful singing and strange exciting music, but it has a cardboard libretto. Danny is simply too perfect--a sweet young man filled with a patriotic urge to prove he's an American by fighting for his country. His mother, likewise, is total virtue and maternal love. Sgt. Marcus is simply a completely evil monster. I'm sorry, all that may make a good news story, but it's just not drama. The story, as presented, does nothing to make the audience more tolerant of minorities; it simply makes us hate those bad guys who did such bad things to Danny. In America we do love to hate, don't we?

Scene designer Andrew Boyce does fine work, rising to the challenges of the rather hop-scotch sequence of scenes. Together with some excellent lighting (by Christopher Akerlind) and wonderful projections (by Greg Emetaz) it presents a shifting, nightmarish environment. The complexity distracts a bit: a towering fire-escape unit trundles on and off, a great fence flies in and out, the turntable turns, the witness stand shifts position (for no apparent reason). But overall it's quite effective.

Stage director Matthew Ozawa manages this complexity with dexterity. James Robinson, who is OTSL's artistic director, served as co-stage director and dramaturg for the production.

The music is so strange, and totally unfamiliar. Who can say whether conductor Michael Christie handled it right? How can one tell if he captured the nuances of the score? All I can say is that Maestro Christie takes a score which is surely very difficult and delivers an evening of exciting, fascinating, and sometimes quite beautiful music.

An American Soldier continues at Opera Theatre St. Louis through June 23.

(Photos by Ken Howard)

Reader Reviews

Videos