Review: A GRIM AND POWERFUL 'GLORY DENIED' at Union Avenue Opera

A soldier gone to a far off war, absent for years. His wife in anguish, not knowing whether she's a widow. It's a story far older than The Odyssey.

Union Avenue Opera has opened a stunningly powerful production of Tom Cipullo's chamber opera Glory Denied. It's a St. Louis premiere. Mr. Cipullo, who wrote both music and libretto, adapted the work from the book by journalist Tom Philpott. And it's all true, right out of the headlines. But it delves far deeper than the headlines. Jim Thompson was gone not quite so long as the hero of The Odyssey, but he was having far less fun than Odysseus.

This is a dark, disquieting work, but you should not miss it. It is so masterfully done.

In December, 1963, Army Captain Thompson left his pregnant wife Alyce and little daughters for a six-months tour of duty in Viet Nam. Three months later he was shot down in an observation plane. His back was broken and he was captured by the Viet Cong. Alyce was delivered of a son on the day her husband was captured.

Captain Thompson was held prisoner, tortured, brutally interrogated, malnourished for almost nine years. When the Peace Accords were signed in 1973 he was released and repatriated. He had been held captive for longer than any soldier in American history.

But the country had changed. How it had changed! And his family, troubled before, now crumbled.

My expectations were not great for this piece. I recently saw an opera about awful things that happened to an American soldier and found it maudlin and opportunistic. My expectations were further lowered when I was told that this libretto consisted purely of quotes from interviews and letters and government documents. (What handcuffs to put on a librettist!) But Tom Cipullo amazed me. Only when the same person creates both music and libretto could such powerful dramatic use be made of such prosaic documentation.

The story is told with only two characters, but with four singers: Young Jim and Older Jim, Young Alyce and Older Alyce. Act 1 shows us Jim in his captivity. Dramatically it's a mosaic: tiny flashes of plot, tiny flashes of emotion--of hope, of despair, of normalcy and of horror, of love and of bitterness. Young and Old characters share lines or overlap. We leap instantly from present to past to future. It's almost pointillistic. And it works! The juxtaposition of all these emotionally contrasting fragments devastates our hearts. What it evokes is not pity (which is such a distancing emotion) but empathy.

Director Scott Schoonover's orchestra of nine supports the emotions, though it's music is often barely related to the vocal line. It varies from brutal dissonance in the prison camp to the sweetly lyrical domesticity of home.

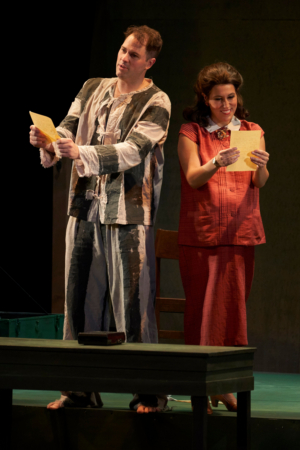

Te nor David Walton as young Jim shines with commitment, and Katrina Brazas makes young Alyce the idealized young wife of his dreams. Fine work by both.

nor David Walton as young Jim shines with commitment, and Katrina Brazas makes young Alyce the idealized young wife of his dreams. Fine work by both.

The years pass.

Now, after so long, Alyce has given up hope and persuades herself that Jim is dead. A family friend becomes a companion, then a suitor. Alyce is not Penelope but a young mother with small children, and by the time her long-lost husband returns she is living with this other man--who has become a father to her childen.

Jim and Alyce attempt a reconciliation but too much damage has been done. Damage to this marriage and damage to the soul of America.

Peter Kendall Clark, as Old Jim, triumphs in one Vesuvius of rage at all the social changes that have happened--and at his faithless wife; it's fierce and complex and much more demanding than any Gilbert and Sullivan patter song. Gina Galati, a favorite of our opera world, sings Old Alyce and is particularly moving when she sings "He went through hell . . . but so did I!" and in her painful "After you hear me" aria in which she offers to leave Jim if he wants her to.

This damaged man commits to surviving in his damaged world "one day at a time"--with the same grit which allowed him to survive captivity. But in the end that admirable tactic is not so successful against the horrors of modern America as it was against those of his jungle prison.

Stage Director Dean Anthony brings crystal clarity out of what is often a potentially confusing vocal pastiche. He leads these singer/actors into deeply engaging performances. The endless shower of government and Army letters of support are well-intentioned but useless bureaucratese--and become almost harrassment. Act two shows the stage slowly filling with pages of such wasted paper. One delicate heart-rending touch comes when each of the four actors reads a letter Alyce had written to Jim early in his Viet Nam tour; enclosed is a small golden paper star that one little daughter had made for her Daddy; it flutters gently to the floor.

The one directorial flaw, I think, was the introduction of a slide-show towards the end; we see photos of the real people, the war, the prison camps. This is unnecessary and indeed distracting. The characters and the suffering in this performance are wonderfully real to us without these photos.

Roger Speidel's set is simplicity itself--a table, a few chairs, some foot-lockers for props and costumes. In the background are great dark slabs like ghosts of the Viet Nam Memorial in Washington. Teresa Doggett's costumes are correctly military and period.

Glory Denied, at the Union Avenue Opera, is a kind of tragedy. We stand in awe at Jim's ability to endure, but he is not without flaws. We cannot even condemn the faithless wife, whose outward anger is more deeply directed at herself. There are no villains--not the war, not the Viet Cong, not the Army--only the Fates which set these events in motion.

It's a beautiful show and it continues through August 24.

(Photos by Dan Donovan and John Lamb)

Reader Reviews

Videos