Interview: Robert Kelley Looks Back on His Amazing 50-Year Run at the Helm of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

2019 Regional Tony Award for TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

(Photo by Shevett Studios)

It is time for Robert Kelley to take a richly-deserved curtain call. June 30th will be his last day as Artistic Director of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley after a mind-blowing 50 years in that role. It is not hyperbole to state there isn't another individual who has had a more profound influence on the Bay Area theatre landscape. Kelley founded TheatreWorks as a scrappy, community theater company in April, 1970 and guided its transformation over the years into a Tony-winning powerhouse and nationally-recognized incubator of new works.

50 years is a long time! Think about it. When Kelley started his job in April 1970, the Beatles were still together and "Let It Be" was their current #1 hit, Nixon was just 15 months into his fateful presidency, and the term "Silicon Valley" had yet to been coined. It was definitely a different time. And yet - through all these years TheatreWorks has remained true to its original ideals of collaboration, innovation and diversity.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Kelley earlier this spring to discuss his half-century history with TheatreWorks. Even after 50 years, he exudes the wonder and enthusiasm of a theater neophyte and eagerly looks forward to the future, even as his tenure ends in a decidedly different fashion than he had imagined, due to the Covid pandemic. He also remains singularly self-effacing and appears most comfortable when lauding the essential contributions of his colleagues.

It should be noted that while diversity and inclusion were discussed at some length, our conversation took place prior to the recent murders of several African Americans and the international coalescence around the Black Lives Matter movement so those events were not addressed. To learn more about TheatreWorks' commitment to racial justice, please visit their website. As announced back in November, Tim Bond will take over as Artistic Director on July 1st and would seem to be an ideal fit for that role at this specific moment in time. As has so often been the case, TheatreWorks is perhaps a bit ahead of the curve. Kelly and Bond have also had the luxury of collaborating closely for the past several months to ensure an optimal transition.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What did you honestly think you were signing on for when you started TheatreWorks back in 1970? What were your hopes for it at that point?

Well, it was [supposed to be for just] one production. It wasn't create a theater company. It was create a new work of theater, and hopefully something that was musical. We began in April and started assembling a group of young performers, writers, composers and tech people with the goal of writing a new musical that essentially would be about us and our community. Believe it or not, now that we see ten new musicals written every day, there weren't in 1970, and especially not in the suburbs of what was not yet the Silicon Valley.

Who was your intended audience?

Well, we hoped that we'd find people who were of similar age and background who would come. I was just kind of out of college. I'd taught school for a year back East, and I was in the area working as an actor with a degree in English Creative Writing out of Stanford. Writing was a big part of what I wanted to do, but this opportunity came along, which was really intended to be just a summer project. We didn't have dreams of the future. It was a big enough dream to see if we could get a show written and rehearsed and built in a six-month period. I mean, we thought probably relatives of the people involved would want to come, and beyond that we hoped we might activate the community because that play, it was called Popcorn, was about a very divided community. Of course, Palo Alto was our point of origin, and so we set our play in Scraggly Tree, California. And it was really about the divide between the young culture under 30 and the adult culture over 30, trying to find common ground and a way to come together despite all kinds of antagonism.

The material we were working with and developing was exactly on that moment of time. Our show started out with a film of almost like a news reel of the era and of a student demonstration that got out of hand and the police showed up and people were being arrested. About five days before we opened in July, there was a big student demonstration in downtown Palo Alto, something like 400 kids, and at least two or three hundred of them were arrested, even as we were in our final dress rehearsals for a play about exactly that. We hit the news, we were kind of the movie of the week and our show became a big hit. It brought in a lot of people from the community and got a lot of talk going about the issues of our play. It was entertaining, it was funny, but it was also about things that were very important to all of us. It was a very diverse cast and that was exceptional at that time in a largely white suburb, in a community that had not yet become the amazingly diverse Silicon Valley.

The arc of TheatreWorks over 50 years has been basically the exact arc of the Silicon Valley as it has changed. I feel like one of the reasons we've been able to succeed is that the values of TheatreWorks reflected the values of the emerging Valley - of innovation, of creating new things, and of fierce commitment to diversity. OK, the tech companies aren't making musicals, but they are accessing art in a whole lot of different ways, without perhaps realizing it. We've fortunately been able to grow quite a bit into a medium-sized regional rep with a lot of support from individuals here in the Valley.

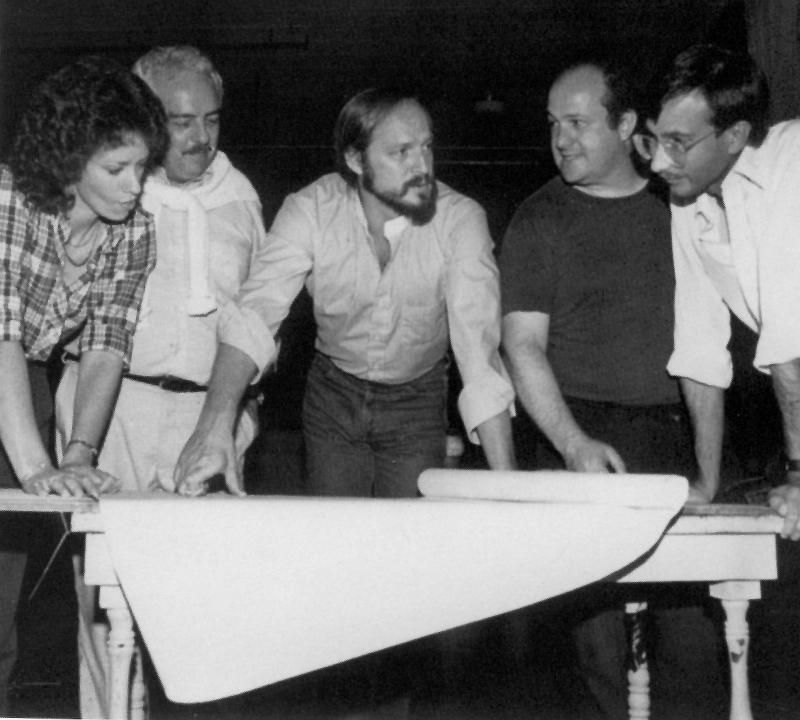

(Photo courtesy of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley)

Founding artistic directors often don't last all that long in the role, presumably because the skills needed to create an organization are not necessarily the same ones needed to sustain it. What qualities or abilities do you think you had that made you the right person to grow the organization over the long run?

Well, I think I am extremely committed to the process. I'm both a believer in, and an understander of, what collaboration really means, the idea that theater is an artform created by a large number of people. It didn't take me long to realize that each person brings something to the process that they're good at, that they do better than anyone else on the team, and if they weren't there, you wouldn't have as wonderful a work of art. I think I communicate that belief very well to all the people I've ever worked with. The idea of giving your all to something is infectious, it is one of the aspects of theater that bring people to it as artists, as folks who want to work in collaboration with others to make something new. And that I think has been a real important part of TheatreWorks. You really can talk to just about anybody who's worked here and you'll hear that they felt valued because they were essential, and everybody knew that they were essential, whatever their role was.

When you're working together with a common purpose like that, before you know it, you start realizing that it's a family, or at least it's functioning like a family. Granted it's a family that lasts til the end of the run of a show, but then there's another one just ahead. Sitting in an empty theater after the whole show finished and the sets came down I found exceptionally inspiring - that we begin again.

Let's face it, 50 years is a long time to hold down any job, even a great one.

I've heard that! [laughs]

What's kept you engaged and excited to come to work every day for all those years?

I think one of the aspects of theater that makes it especially exciting is, in our case, at least every six or eight weeks we're beginning something new. It resembles in some ways something else we might have done, but it is a whole new product. If we were a tech company we'd be rolling out a new product every two months or even sooner than that, and the team that creates it is all new. There's also lots of people who come back not just as artists but on our staff and it becomes this extended family where every week there's somebody from the distant past who's there to remind you that you're part of an ongoing, amazingly large family that still today remains committed to making art.

I have really never experienced any desire not to keep making theater and not to keep making it here in this immensely supportive environment. I'm retiring really only because I want to make sure the company is in great hands as it moves forward into the next half-century, realizing that I'm not going to be available for the next 50+ years. [laughs] But there's also strength in renewal and Tim Bond, our new Artistic Director, is - you could scour the entire landscape of American theater, which we did, and find this is the person who is best suited to take the reins here at TheatreWorks. So I am very, very excited about this transition and of course I'm not going anywhere. I'm healthy and I'm looking forward to continuing to support the company in any way possible. I think we'll be launching a new era, but it will be an era built on those same basic principles that we established on our very first show, of innovation and the intersection of music and drama in a way that had meaning in terms of our community and in terms of our lives as human beings. Of course, our commitment to diversity is very, very strong in terms of our programming, our casting and all of that, but I expect Tim will continue in supporting all the values that TheatreWorks has embraced from the beginning.

I've had the pleasure of interviewing several TheatreWorks folks over the past year. Francis Jue was especially grateful to you for giving him opportunities as an Asian-American actor that others might not have. He said you saw something in him that he himself just did not see. That's quite a testimonial! At TheatreWorks, you were doing, for lack of a better term, non-traditional casting long before it became common practice elsewhere. Was that a conscious decision on your part at the time?

Well, the company had certainly been known for diversity in its first decade, but we were also struggling to establish our identity, to grow and mature as an arts organization. By the time that we got to the 1980's, our commitment to diversity crystallized in a stronger way. A wonderful African-American actor and director named Anthony Jay Haney became our Associate Artistic Director. Together, he and I really set our minds to expanding our commitment to performers of all races, to ethnicities that might be underrepresented. We did, as a result, become a leader in what was then called non-traditional casting, but also in culturally diverse programming, in terms of what we were putting on in our season. In many ways it did distinguish the company from where everybody else was at that point in the American theater.

But I think as Francis pointed out, that was not common, certainly in the world of Broadway and most theaters, and we proudly set forth on sort of a regimen that created this amazingly diverse community onstage. I don't want to say it was a natural outpouring of the culture of the Silicon Valley that was forming around us, but in fact it did reflect exactly what was happening. People from all over the world and from all races and ethnicities were populating our region and bringing in amazing skills. That's how Francis wound up playing Mozart and Peter Pan and a whole lot of other things. And Tony, too, wound up playing a lot of different roles, as have a lot of other actors of color at TheatreWorks.

We were also able to do Pacific Overtures which no one had thought you could possibly produce in the Bay Area. We actually wound up doing it twice. I think we're the only regional that's ever done it twice, and that was the same kind of adventure. That was not non-traditional casting, other than that there was the idea that assembling a large Asian cast for a huge project like that simply did not happen in the Bay Area.

I remember seeing "Pacific Overtures" at TheatreWorks and it just blew me away.

Great!

So how did you pull that off?

Well, Francis was the lead in our first production of it and he was the choreographer for our second production. You know, you get a couple of key people and back it with a fierce commitment to making it happen and off you go. I mean, it wasn't that you weren't seeing productions that had Asians. Flower Drum Song and those kind of shows occasionally would get done, but this one was extraordinarily different from the traditional kind of large Asian pieces. And we found people from all over the Bay Area. It's interesting, but in those days you really didn't have actors traveling from one end of the Bay Area to the other to be in shows. It was pretty rare.

I certainly talk to a lot of actors now who seem to work all over the Bay Area.

They do! But it was not all that common. It became common at TheatreWorks because we were doing shows that people wanted to be in, and also shows that were open to musical theater actors and dramatic actors who were woefully under-utilized in the Bay Area. Their opportunities were very limited. As Francis said, these were opportunities he wouldn't have gotten anywhere else. And that's actually, sad to say, at least at the time, true. We were doing shows like Pacific Overtures that had close to 30 people, all Asian American or from various countries of origin - and they came from absolutely all over the Bay Area. We did a show called Go Down Garvey, a world premiere musical about Marcus Garvey that actually opened the Mountain View Center for Performing Arts. That had a cast of 33, I think 31 of them were African American, and some traveled an hour and a half, two hours to get there to make this happen. And that was just unheard of, a show like that in a suburban theater in California. On the other hand, both of those became huge, runaway sellout hits.

I don't know how to ask this in a way that doesn't force you to give some sort of uncomfortably self-congratulatory response, but I feel like a few decades ago the common wisdom was you couldn't do shows like that because you couldn't cast them, you couldn't find enough qualified actors. You obviously didn't buy into that.

Well, it was definitely the perception. In our case, each time we made a decision to put one of these shows on the season, say the first time doing a show with a very large cast from a specific culture or race, the question was "How are we going to do this?" and then we went out and did it. You just put the energy in. Part of it was the inclusiveness of the company at its core, of having key people who could access those communities in ways that, if it'd just been me, I probably wouldn't have known where to start. But there were people who did know where to start, who stepped up. As I said, in every part of a production, someone is the right person to be brilliant at doing something. You put it all together and you have something brilliant onstage.

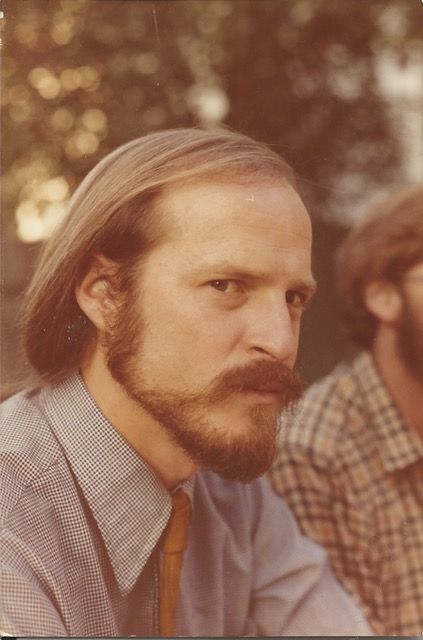

(Photo by David Allen)

I also wanted to talk about your approach as a director. When I spoke with [director] Leslie Martinson last summer, I asked her what she'd learned from working with you so closely over the years. She said "He's a very visual director. For Kelley, what it looks like is what it means." Would you agree with that observation?

I would agree with that 100%, and it's what I've always believed. When I first started directing, I bought a large book of paintings by Renaissance masters. Part of it was I was suddenly directing big groups of people, and I had no idea how to do that. I just sat and stared at these paintings for hours trying to find out how they did it. And I think that's really when the impression was made that how it looks is in fact what it says. I mean, part of it is that a painting doesn't talk [laughs], but it says a lot. That's really where I got started with this idea.

I think I sometimes drive our actors a little crazy with trying to get the look of something just right. I let them understand they're in charge of getting the meaning of it in their hearts and souls, that I will guide them, but I need to rely on them being brilliant in that part of the process. But I will make sure that what people are seeing is supporting what they're saying and thinking, and it really is true. The few times I've taught a class in directing or making new works, I get a couple of people together, have them stand face to face and say "Imagine this is Romeo and Juliet." If they're this far apart, they aren't Romeo and Juliet. And put 'em too close together, they still aren't Romeo and Juliet. There's a place that we as human beings recognize that says "that's love."

Did you have a thing for Renaissance art in particular? Why did you pick up that book?

Um, that's a long time ago! [laughs] I thought it was cool. I had really taken an interest in Hieronymus Bosch way back then, but I was always interested in Renaissance art. I came out of high school as a history buff. I just have always been fascinated by the process of history, in the way it repeats itself, in sometimes brilliant and other times horrifying ways, and I think that has certainly colored our choices. Our choices are made collaboratively here at TheatreWorks in terms of what we put on stage, but I'm a big part of it, and that has been sort of the fascination with history and art that's led us to a lot of shows.

I mean Pacific Overtures is a historical musical or Ragtime certainly is a great example. There's so many and they take all kinds of forms. Sunday in the Park with George is sort of historical, but mostly it's Sondheim's play about making art, so there you go. There's been a lot of artists whose work has been represented on our stage over the years. If you had to sit down and analyze the 400+ shows we've done - I don't know the actual number, 430 or something - that's certainly been a trend.

You've had countless successes over the last 50 years, but I assume you've had some disappointments along the way, too. As a director looking back on all the shows you've directed, are there any that stand out for you where you feel like you didn't quite get it right?

[Pauses] Well, here's an experience that all directors have, not necessarily on every show, but on many shows. It's three months after you opened and suddenly you pull over to the side of the freeway and you go "How could I have done that?" or "How did I miss that? I can't believe it. Where's the time machine? Take me back. I can fix it now!" Rather than give you a specific example, let me tell ya, I pulled over to the side of the road many, many times.

And you know, there've been plays I thought would soar in the public's eye, that I thought we made beautiful productions of, but that didn't ring, didn't register at all. Those always set you back, especially in my case because I was raised here in this area and have lived here all my life. You feel like "Wait a minute. I thought that I knew our community as well as you possibly could." When a show doesn't captivate or doesn't electrify our audience, I take it personally. I feel like I missed some part of the culture. That's happened a few times.

But you learn from that, right?

Oh yeah! [laughs] We used to do at least one Shakespeare a year because we had an outdoor theater for 17 years. We kind of had the same situation that Cal Shakes had where we were in an outdoor theater in a neighborhood in the summertime and did Shakespeare productions, a lot of them. Eventually it became too much for a few neighbors and we had to close. We've still done Shakespeare occasionally, but there are wonderful offerings in the Bay Area that are certainly holding down the fort for Shakespeare lovers. Years later, we put on a show that had a lot of Shakespearean references in it and we realized once it got up and running that our audience, in the absence of doing Shakespeare on a regular basis, just didn't follow all of the references. So it's not a 100% cohesive audience that we're all playing to. There are differences, and in some cases, ones you didn't anticipate. I'm sure you've seen the many different theater companies in the Bay Area, that the audiences are not identical by any means. I think you can attribute that to the combination of communities being served by the theaters, but also by the choices of the artistic director or the artistic team.

And as an artistic director you want to give your audience something they're going to enjoy and get something out of, but you also want throw in some things that maybe weren't expecting, right?

I think that's the nature of art, that you are representing the world. I think you have an obligation to address issues that are relevant to your community. I love alliteration unfortunately, and I sometimes dwell on both the potential and the prejudices of our community. We certainly have a reasonable amount of both, and that exploration has always been part of TheatreWorks. I mean, from our very first show we have looked at the issues of our times. Some of them are the small, interactive issues of human connection, and some of them are the large, complex political issues of any given era, but they've always been presented here in the light of a belief in human potential. I guess we're still stuck with a phrase we started in the 70's here which is "a celebration of the human spirit."

Once you actually step down as Artistic Director, what are you most looking forward to letting go of?

Well, I'm both looking forward to and imagining with trepidation not coming into the office every day. It is just going to be very different. In some ways it'll certainly be liberating, but in other ways I don't really know how I'm gonna feel when every day isn't like a Thanksgiving dinner with a very, very large family. I guess I'm looking forward to what that portends, but also kind of worried about a part of my life that will change dramatically. I always used to, when I'd get really tired at times, go home and look in the mirror and say "What part of 'full-time' didn't you understand?" [laughs] And that has seen me through a few difficult times. But, yeah, I think that'll be a big change.

When we worked out the upcoming season, Tim [Bond] very graciously asked me to direct Sense and Sensibility, the Paul Gordon musical. It's kind of the third part of a trilogy of Jane Austen musicals and I was very proud that Tim had confidence in me and was eager to have something that I was working on in the season. And now, as it's turned out with this Covid crisis - I warned you about alliteration, didn't I? - that with the postponement of Ragtime I'll wind up doing two shows next season. That's much beyond what I'd expected to do, but I am absolutely thrilled.

Is there anything new you're looking forward to taking on once you have some time to yourself?

Well, I have done a little teaching at various places over the years and I think I'm going to start looking around to see if anybody might be interested in another old white guy with a lot of experience to share. [laughs] I did a class at Stanford a couple of years ago in how to make a new musical, and I found it tremendously rewarding and just plain fun and exciting.

And there's always been a part of me that liked working with young performers. It's difficult to work with kids at a professional level these days because it's so very, very expensive to do, but fortunately we've hung in there and managed to do shows that have kids in them. Actually last year there were two shows that fit that bill, Fun Home and Tuck Everlasting. I just love the experience of young artists not only discovering their own potential but recognizing the potential of a career in the theater, and also recognizing the immense amount of talent it takes as they work with pros not just from around this region but from all around the country and from Broadway. I've found that a thrill, and in some ways it's reproduced when you get a chance to work with young, college-aged students who are excited about theater in every bit the same way we were on that first day of April, 1970. When I'm with a group of students like that, I really can't help but remember the process we launched then and have continued ever since.

(Photo courtesy of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley)

Videos