Interview: Francis Jue of THE LANGUAGE ARCHIVE at TheatreWorks Talks about His Unexpected Journey from Sondheim to TheatreWorks to Hwang & Tesori to 'Madam Secretary'

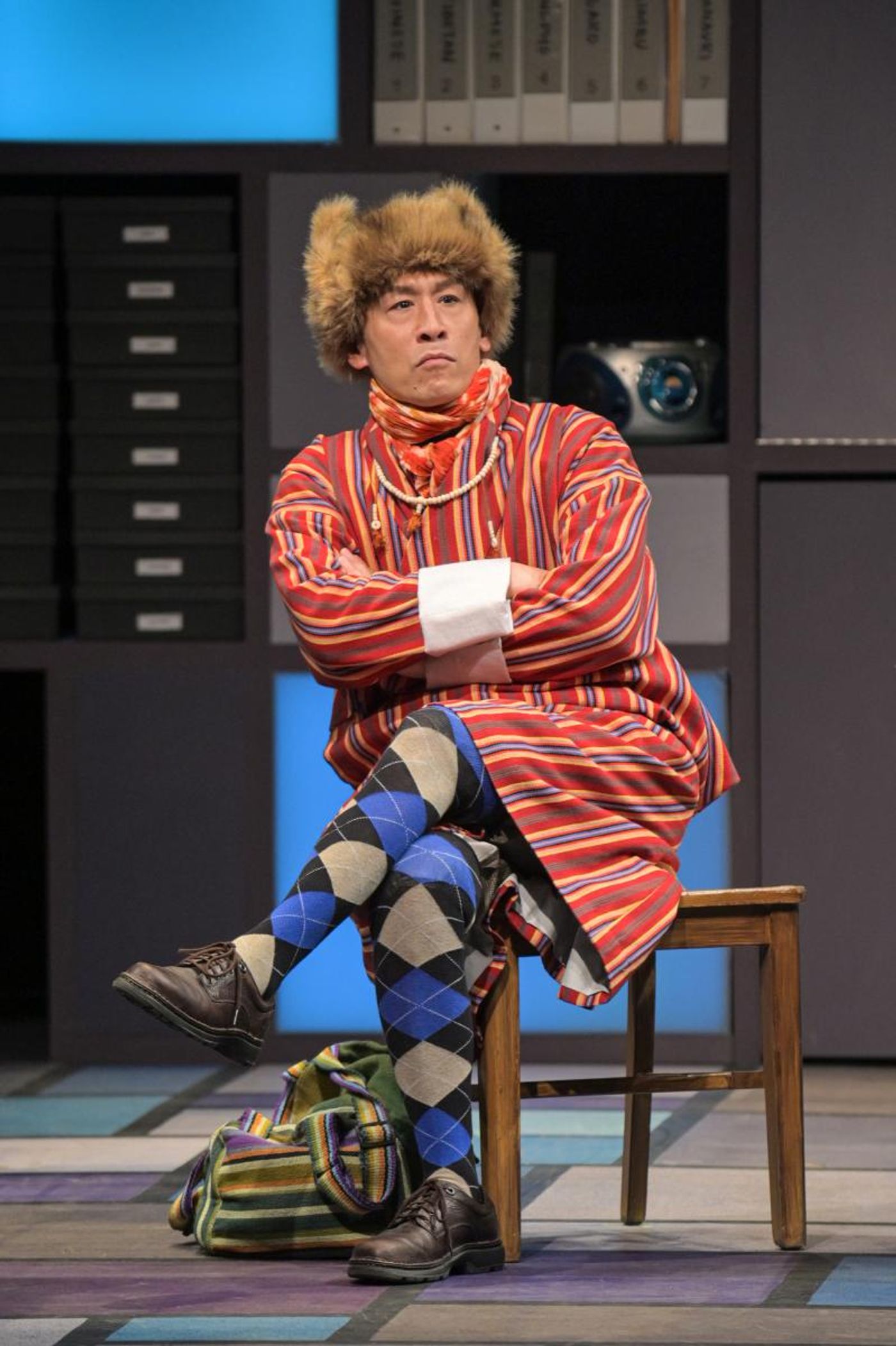

Photo by Alessandra Mello

Broadway and TV actor Francis Jue is currently starring in TheatreWorks' production of Julia Cho's "The Language Archive." Mr. Jue recently talked to BroadwayWorld about his lengthy and surprising career path, from his formative experiences with Stephen Sondheim and TheatreWorks to working with Tony winners David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori, and of course his continuing role on the CBS television series "Madam Secretary." His fascinating story serves as an inspiring example for anyone who doesn't see a clear path to success or struggles to find a place to fit in. The following conversation has been edited for length.

In this city of immigrants and refugees, you are that rare individual who is an actual San Francisco native. How is it for you to be back working in the Bay Area again?

I think I will always be a San Francisco boy at heart. I went away for college and I live in New York now. For nearly 30 years I've travelled for work, but I think I will always feel more at home - my blood pressure, I think, will always be a little lower - whenever I'm back here in the Bay Area. Most of family live here in California and so I love being back. And TheatreWorks itself is a real artistic home for me as well. One of my first professional opportunities was with TheatreWorks and they've continued over the last 30-some odd years to find opportunities for me and I've learned so much with them.

The publicity for "The Language Archive" alternately calls it a "quirky comic drama" and a "romantic parable" which is a little cryptic. As someone who is currently living inside the play, how would you describe it?

The brilliant Emily Kuroda and I play a married couple, the last known speakers of our language, and we discover through the play that there's a limit to the amount of time we have to say the right thing to one another. While working on "The Language Archive" I've really fallen in love with Julia Cho, the playwright, because she finds what is hilarious and what is incredibly moving about these characters - about our unique human potential for connection, for understanding, and at the same time, the limits on that understanding - the limits that we choose sometimes, the limits of our capacity for understanding or communication, and sometimes the limits imposed by life. I find the show incredibly funny - I haven't laughed this much in a long time - but it's also incredibly moving because we are human and we make mistakes and we sometimes aren't meant to be together. And Julia finds value in all different kinds of love, all different kinds of relationships, and I find that really beautiful. I feel like I get her language and I get her sense of humor and I feel like she invests a lot of herself in her plays. It's not just an intellectual exercise; it's a very human experience working on Julia's plays.

Emily Kuroda is, like you, an accomplished stage actor also widely known for her TV work (including playing Mrs. Kim on "Gilmore Girls"). Had your paths ever crossed before?

She and I worked on Mike Lew's "Tiger Style," an incredibly funny play, and she and I were a married couple in that as well, and she is just - I can't tell you how inspiring she is. She can do no wrong in my book. She has such a huge arsenal of experience and skill and I think she's one of the funniest actors I've ever worked with, and at the very same time she can break your heart. I never see her acting. It always feels incredibly genuine to me, even when she's playing wildly eccentric characters. I just feels authentic to me, and so I adore her.

You've maintained a thriving and varied career for some time now, which is a challenge for any actor, let alone an Asian-American one. And as you've matured, it seems to me that if anything the roles you're getting are increasingly complex and interesting. How have you managed that? How do you choose which roles you're going to pursue?

You know I think "manage" is the wrong word. When I was much younger, I never thought that I would do this for a living. I doubted whether I had the capacity to do well in this, and yet I knew this is where I belonged, from the moment I saw my very first live musical, a high school production of "The King & I." My family only went to go see it because my brother was playing the prince. We weren't really a theatergoing family, and yet I knew that that world was where I belonged. There was something spiritual about being able to collect strangers in a room and have a shared experience.

When I first started performing, there were many people who told me I had to choose whether I was going to be a musical theater performer or an actor. There were people who told me that I had to choose whether I wanted to work as an Asian-American actor or whether I wanted to work non-traditionally. At the time, that meant working exclusively on classical theater because people weren't doing a lot of non-traditional casting in other areas, and frankly there weren't a lot of people doing Asian-themed plays either. My very first professional gig was a [1984] revival of "Pacific Overtures" in New York. I was still in school and there I was surrounded by Asian-American actors making it in the business in one way or another, and yet I still couldn't believe that was a path for me. So, I went back to school after having done that production.

In 1988, I was working at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation when I auditioned for a TheatreWorks' production of "Pacific Overtures" and I was their first equity contract actually. And there I was, working with [Artistic Director] Robert Kelley, in this production full of people, some of whom wanted to pursue performing professionally and others who didn't. And yet he treated us all like professionals. Subsequent to that production, he cast me as Peter Pan. He had managed to develop an audience that had no qualms about seeing not only a man play Peter Pan, but an Asian-American performer. To him, treating me as a professional was not strange, was not a leap of faith. And I think it was because of his faith that I began to see that I could be a professional, that I had something to offer, that I had my own voice, my own esthetics, my own judgment. Over the course of 30-some odd years, he's cast me as Mozart in "Amadeus," he's cast me as a reporter from Kentucky in "Floyd Collins," he's cast me in a number of things that no one else was thinking of me for.

And in addition to that, in New York, I started working on new plays like "Yellow Face" with David Henry Hwang, like "Tiger Style" with Mike Lew, and like "King of the Yees" with Lauren Yee. Over time - and it's taken decades! - I think I have finally come to regard myself as a professional as well. I feel really lucky that people have continued to offer me opportunities in a wide variety of things and have challenged me to see what I have in common with all of these different projects. I think one of the things that has helped me throughout all of these years is the fact that I never really thought I could do it, and so I have maintained a student's attitude about all of this. I don't assume that I know better. I don't assume that I understand until I get in a room and I work with people. For me, that work has been my study, that work has been my real passion. And so I think it's that kind of collaboration that has recommended me to people.

In the 1984 Off-Broadway production of "Pacific Overtures" you got to perform "Someone in a Tree," which is considered by some to be the best song Stephen Sondheim has ever written. It's an incredibly complicated, haunting and thrilling 7-minute opus about memory and being a witness to history in the making. What are your own memories of that experience?

I remember ... First of all, I only got that show because I had gone to school with a musician who had already graduated from Yale and was playing audition piano for this revival, and they were having trouble finding someone to play the Boy in the Tree. He called me up and he said "Are you in good voice? Do you want to come to New York?" I had never taken the train to New York from New Haven before - this was my junior year in college, you know - so he picked me up from Grand Central and he ushered me to my audition and I sang a couple songs for them and I did a little soft shoe. We rehearsed in this teeny little children's classroom for pre-schoolers where, you know, the chairs were a few inches off the ground. So from the beginning I've considered working in this business as school.

I remember we performed that original revival in the children's gym, with the basketball hoop above the set, and 99 seats, and Sondheim came to see our final performance. He was so impressed he came backstage after the show and we were all in a circle, listening to him talk lovingly about our production. Then somebody tapped me on the shoulder and said there were people waiting for me. I didn't know anyone in New York at the time and I was like "Who?!" I didn't know this, but one of my brothers had flown my parents out to see the show and so, bawling, I pushed right past Stephen Sondheim to get to my parents. I just remember them being bowled over. They had warned me that if my grades slipped, they were going to cut me off, because I was commuting between school and doing the show at the same time.

After Steve saw the show, he recommended it to The Shuberts and to McCann & Nugent, who were big Broadway producers at the time, and they decided to mount the show commercially Off Broadway the following season and so I took a year off of school. And my parents said, "OK, well if you've got a job, we're not subsidizing you. This is what you've decided to do." At the time, I was making something like $250 a week and I had to join Actor's Equity and I was living in an apartment of my own for the very first time, I had my own room, and I thought I was rich - and yet I still didn't think I was going to do it for a living.

I remember Steve Sondheim telling me that he was having trouble figuring out a song that he was going to write for "Sunday in the Park with George." He knew that he wanted to write something for Bernadette [Peters] in Act 2, but he wasn't quite sure what it would be, and he told me that he was watching me sing "Someone in a Tree" and he suddenly had the idea for "Children and Art" and he started writing that song on a cocktail napkin at intermission. Now I can't take any credit at all, but I just thought that was one of the most beautiful things anyone has ever said to me. And, even so, I went back to school after that, I got my degree in English Lit, I never studied Theater or Acting in school and went back to San Francisco where I got a job at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, because another passion of mine was the AIDS crisis.

Years later, I got a call from Meg Simon, who is a major casting director in New York. She had seen that production of "Pacific Overtures" and said "I'm the casting director for 'M. Butterfly' on Broadway and one of these days BD [Wong] may leave and his understudy will take over the role so we'll need a new understudy. I am coming to San Francisco and I hope that you will audition." And I don't know how she found me, but I said "OK, I'll audition for you." and I thought it was just going to be good practice. I read for her and she gave me a handful of notes on my reading and said "I don't know when we're having callbacks because we don't know when BD will leave the show, but think about it." Months later, I got a call from her saying "At the end of the week, we're having callbacks here in New York, onstage at the Eugene O'Neill Theater. Can you be here?" And I was working with a non-profit and I couldn't afford to buy a ticket that week to go to New York so I said "Who's paying?" and she said "Can I put you on hold?" and in the time she put me on hold she got the producer to agree to pay for a plane flight, a night in a hotel, and a house seat to see the show the night before my audition. I didn't know what a big deal that was at the time or how ballsy it was to ask her for that!

So later that week I flew to New York, dropped my bag off with coat check at the theater, and watched the show with a notepad on my lap writing down all of the blocking while I was watching the show. I stayed up all night, didn't sleep a wink, practicing the blocking from the show. The next morning I got up and walked through the stage door and I thought "I'll never be on a Broadway stage again so I might as well just pray to the gods of Mary Martin and, you know, Carol Channing and just enjoy this." I did four scenes they had asked us to do, and after I was done, I went back into the wing to get ready to go to the airport, and the casting director, Meg, ran to thank me. She said "You remembered the notes I gave you and you made me look good so thank you very much." Not long after that, I got a call at work from the company manager saying you've got to get yourself to New York by such and such a date to start rehearsal. I had to quit my day job, I had to find a place to live in New York and I wound up asking the wardrobe supervisor from that "Pacific Overtures" I did back in 1984 because I remembered that she'd had a small second bedroom. I said "Can I stay there until I find a place to live?" and she said "Sure!" and I wound up living with her for something like the next 27 years.

So - that original production where I played the Boy in the Tree really changed my life. The perspectives that are described in that song ["Someone in a Tree"] about memory and about how we see these slices of our lives without knowing the larger implication of things is exactly what was happening with me at the same time that I played that part.

You played Bun Foo in the original Broadway cast of "Thoroughly Modern Millie" some years ago. I saw that production and still have fond memories of your performance. It seemed to me at the time you were making fun of, and thus effectively subverting, Chinese stereotypes. In more recent productions, however, the Chinese characters have been called out for perpetuating problematic tropes. Given that you originated the role of Bun Foo, what were your thoughts at the time, and have they changed at all over the years?

You know, even at the time, I had fears that people would not understand. I took great pride in the way that we were playing Mrs. Meers and Bun Foo and Ching Ho. We were presenting Asian stereotypes that were very common at the time, in the 1920's, but our characters were being allowed to comment on that and to show how wrong that was. We were also portraying characters who, like every other principal character in the musical, were coming to New York to make a new life - and we wound up being the heroes of the story. Ching Ho winds up saving the girl, the ingenue, and Bun Foo winds up ensnaring Mrs. Meers, capturing the villain, and acquiring a job to pay for his mother to come to America - so you know fulfilling the American dream.

So I still am very very proud of what we did, but I was very aware that there wasn't enough in the script - it was just literally what was on the page - to prevent people from doing different things with the show, and simply portraying stereotypes without commenting on them. I think that there probably have been productions of that show that are racist. There definitely are ways to do that show that are offensive. I do not believe that the production I did was offensive and I don't know that now, with our current sensibilities, is the right time to do that show. Because I think we still have a long way to go. I give Michael Mayer and Jeanine Tesori and Dick Scanlan a lot of credit, I give Harriet [Harris] and Ken [Leung] and I a lot of credit for seeing the humanity in these characters and portraying that. I think oftentimes people don't do that simply because these brothers are Chinese. They turn them into jokes instead of the human beings that they are.

I'm really grateful for that experience. It was one of the first times that I had originated a role, let alone originated a role in a big-ass Broadway musical, and I learned a great deal about collaboration and about theater and about comedy from that show. I also learned that as an artist, I can't control other people's experience. Yes, I'm a storyteller and therefore a guide to a story, but ultimately I don't control what other people see. I'm not living their lives as they're watching the show. Part of the point of live theater is that we're all going to have a collective experience, but we're also each having our own unique experience. I love "Thoroughly Modern Millie." I think it's a wonderful show, but I do think that it is possible to do a racist production of that show and so I can't blame people for protesting. But I also think it has potential to be a wonderful example of two Asian immigrant characters who wind up winning and being heroes, and a show where stereotypes are called out for what they are. I wish every production of that show did that.

Your role as the Chinese Foreign Minister on CBS' "Madam Secretary" has certainly raised your national profile. On that show, your character has a very complicated relationship with Tea Leoni's U.S. Secretary of State. There is a mutual respect, possibly an affection, for each other even as you advocate for the often-opposing interests of your two countries. How do you see the relationship between the 2 characters?

I'm really grateful to the folks at "Madam Secretary." There was no guarantee that it was going to be a recurring character when we first started to shoot. Five seasons later, I am grateful that over time the writers have provided this storyline, this developing relationship between these 2 people. I don't have as much experience on television as I do onstage, let alone having a long arc, and I get an episode at a time so I don't even know what's happened in the meantime oftentimes. What's wonderful is the development of this mutual respect and affection even through they're fighting for their countries' interests, which are often at odds. I think the show has illustrated that there isn't necessarily one objective truth. There are legitimate and also disastrous consequences to both systems of government, to both ways of looking at the world. And I love that it's not just "American Secretary of State good / Chinese Foreign Minister bad." They are both trying to make their countries better and make the world a better place as a result. They're both trying to survive not simply by destroying each other, but by improving their own countries as well. I think the show in a really smart way is a sort of wish fulfillment of how we would love to be able to regard one another, how we wish government could work and evolve. I love that it's a show that centers around a strong woman, who is complicated and has a family life, and has faults and limits of her own. And - I love working with Tea! She's just lovely and generous and smart and I'm so grateful to her.

You appeared in the Bay Area just last summer in David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori's musical fantasia "Soft Power" about US-China relations (which seems to be a current theme for you?!). You played the leading role of "DHH," clearly modelled on your actual playwright. What was it like to work on such an ambitious, multi-layered project? Do you know yet if you'll continue to be involved with the show as it develops elsewhere?

When I first was contacted by Leigh Silverman, the director, who I've worked with on a number of things including "Yellow Face," and "Wild Goose Dreams," and this was a couple of years ago, she said "I want you to attach yourself to a project. We're developing it in the course of the next year." And I said "What is it?" and she said "I don't know, but it's being written by David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori." And I was like "Oh, OK, and who am I playing?" and she says, "I don't know." So here is another example of me just going "OK, I don't understand, I don't know what I'm doing, but I'm going to trust these brilliant, brilliant people who have entrusted me over the course of many years."

And so I started working on this show that I really quite literally did not understand, and that they were trying to figure out, too. How do you write a play with a musical inside of it? How do you write a show that a large part of which was supposed to come from a Chinese perspective? How do you write a musical version of "The King & I" from a Chinese perspective? And how do you write a show where you incorporate David Henry Hwang into the play at a moment of crisis in the country, when you've got our highest ideals in a democratic presidential election that from our perspective doesn't go the way that you thought the wisdom of the masses would determine the outcome? How do you resolve the contradiction in living in a free society where you get stabbed in the neck because you're Asian, by a total stranger? I give David and Jeanine and Leigh and our choreographer Sam Pinkleton all the props for wrestling with this enormous jigsaw puzzle of a show and coming out with something incredibly beautiful and powerful and that speaks directly to the moment we're in. It's one of David's most personal pieces of work, and I couldn't be more scared or more flattered to be entrusted with portraying David in such a piece.

It was one of the most terrifying processes to go through because they were trying to figure this out, I was trying to figure this out what I was supposed to do in it, and ultimately by the end of the show, to stand on the edge of the stage and look at the audience and ask them whether there was anything still worth fighting for, or whether we were just going to give up was one of the most challenging things I've ever had to do. And I still get moved just thinking about the prospect of doing that show again and asking New York audiences, "Do you still believe that in spite of it all this is worth fighting for?" and I can't tell you how much I'm looking forward to doing the show again when we premiere at the Public this fall. Yes, the Public has announced the cast and the dates for the show and I can finally acknowledge that yes, it's happening.

As a working actor, what is the best part of your job?

I get asked by young actors sometimes how to make it in this business. What do they do, what is the key that will open that door? The only answer I have is for them to focus on themselves, to know themselves really, really well. And to know exactly why they're doing it. Why are you in this business? Is it to be a star? Is it to have a sitcom on TV? Is it to work on new plays? Is it to do classical work? Is it to be well known, to be a household name? Be really specific about what it is that motivates them, what inspires them.

And I have to go back to that first time I saw my very first live musical, that high school production of "The King & I." I remember really clearly the curtain opening during the overture and I remember really clearly believing that they were all Siamese, even though in my memory the only Asian actors in that production were the ones playing the king and his prince (that being my brother). And then I remember really clearly the actress playing Mrs. Anna crying as she read the letter from the king at the end of the show, and there were real tears coming down her face. I remember thinking that - and I was such a shy kid, I couldn't talk to people, I was very, very insecure, I hated myself, I really was a problem child, who really didn't have friends, didn't even really play well with my own brothers and sisters, I would get upset - and I remember thinking this is a world that I can live in. Because with a script, and with a dark room where people volunteer to come together, we can have a conversation, and we can communicate about things I don't even know how to articulate yet. It's that connection, that ephemeral connection and that honesty, no matter whether I'm in a musical and singing or whether I'm doing a comedy, whether I'm playing a ridiculous character or a heroic character, I'm looking for that honest expression of humanity that will be in dialog with the other people onstage, with the script itself, with the audience that comes to see the show. When that happens, that I think answers the need that I had as a little kid to live in a world where we actually can communicate with one another.

And that's one of the reasons why "The Language Archive" is so important to me, because it literally is about that need for communication. And I really, desperately wanted to be a part of Robert Kelley's 50th and final season as Artistic Director of TheatreWorks because I owe him so much. Being at TheatreWorks where I've grown up, where I've developed as an artist, where I learned to respect my own voice, to respect myself as an artist, means a great deal to me.

TheatreWorks' production of "The Language Archive" continues through Sunday, August 4th at the Lucie Stern Theatre, 1301 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto, CA. For information or to order tickets visit theatreworks.org or call (650) 463-1960.

Videos