Student Blog: Broadway According to Kurt Vonnegut

Analyzing Musicals With Vonnegut’s Shapes of Stories Theory

In 2004, acclaimed author Kurt Vonnegut stood before a lecture hall of students at Case Western Reserve University and explained his master's thesis-one which was unanimously rejected by the faculty of the University of Chicago in 1947. Several successful novels and twenty-five years of rumination later (on Vonnegut and the faculty's parts, respectively), he was awarded a degree.

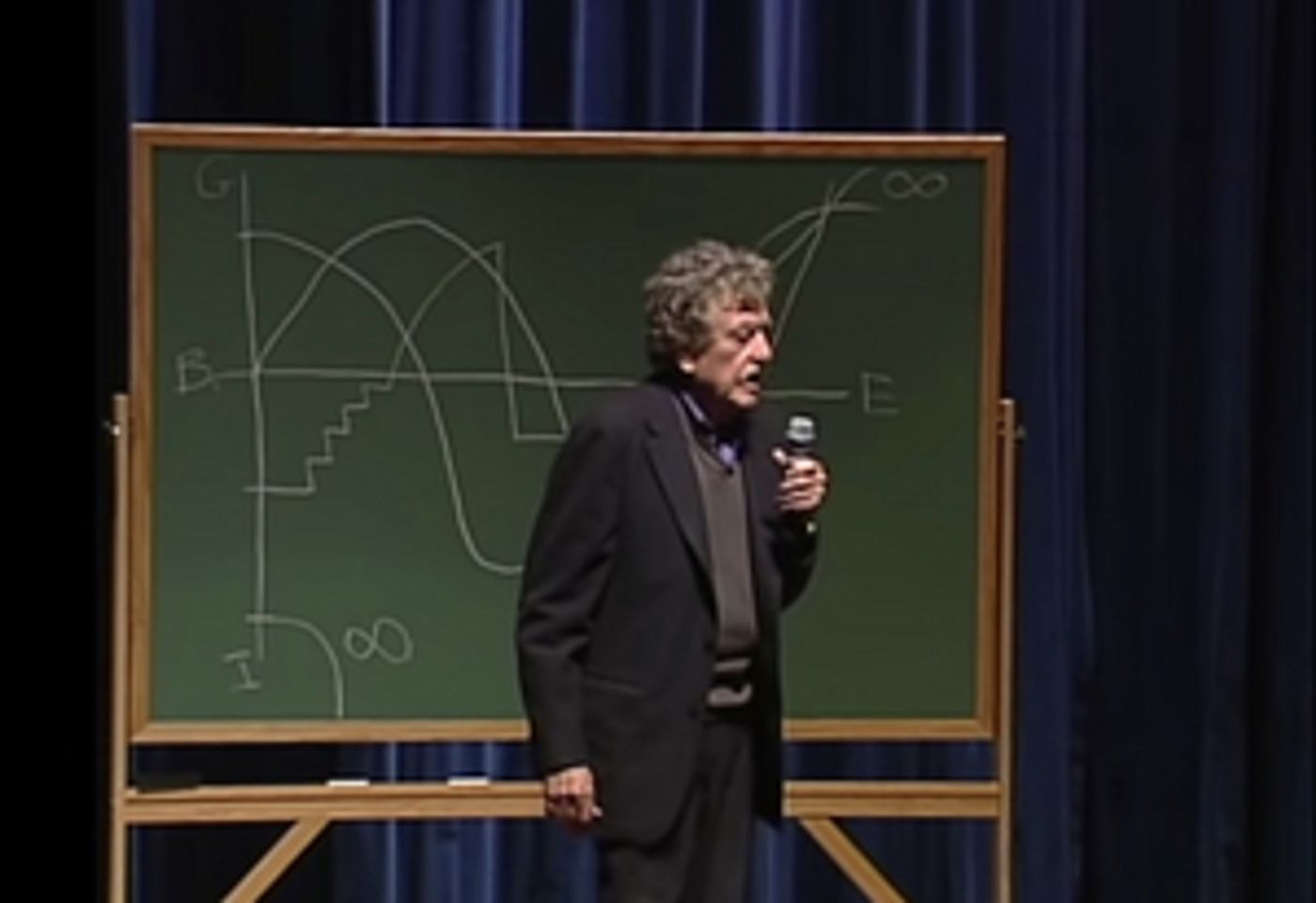

In his thesis, Vonnegut proposed that every story ever told followed a graphable shape-another iteration of the old adage "there are only five stories in the world" with a more mathematical bend. The stories are graphed on two axes: the vertical "good fortune-ill fortune" axis and the horizontal "beginning-end" axis. As Vonnegut draws stories for the Case Western students in the now-infamous lecture, it becomes clear that he's onto something. Perhaps stories aren't as unique as we think they are-and perhaps that isn't a bad thing. Let's unpack Vonnegut's shapes of stories and how we can better understand Broadway musicals through them.

- "Man in Hole"

Vonnegut puts it best: "Somebody gets into trouble and gets out of it again." As simple as this story shape may be-it starts and ends in the good fortune section of the graph, dipping down slightly into ill fortune during the middle-it's effective. As Vonnegut observes, this story is in every book and on every television channel. Some classic Broadway examples of this story include Chicago, Hamilton, Dear Evan Hansen, and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. The protagonist finds themself in trouble and spends the majority of the story trying to get out of the hole (more often than not, digging a deeper hole in the process) before eventually finding an escape route and ending the story on a relatively positive note. Done well, this story will always be timeless and compelling.

2. "Boy Meets Girl"

"I call it "boy meets girl," but it needn't be about a boy or a girl," says Vonnegut, before launching into his analysis. In essence, the boy meets girl story shape is the classic Broadway musical. Things start relatively well and keep getting better until the protagonist meets a challenge and slowly slips down into ill fortune around the halfway mark of the story. In the end, fortune turns for the protagonist once more and they are able to end their story in good fortune. As keen Broadway fans have observed, most Broadway musicals have an upbeat, inspiring, borderline-cheerful first act and a second act that tears the first hour of the show to shreds. Shows like Into the Woods, RENT, The Music Man, and Falsettos demonstrate this concept beautifully: increasing fortune and entertainment during the first act followed by a sharp dip during the second. These are effective because they blend the flash and style of Broadway with the storytelling that makes live theatre so compelling-another story shape that isn't leaving the stage anytime soon.

3. "Cinderella"

Unsurprisingly, all of the Broadway iterations of Cinderella fall into this category. In this story shape, the protagonist starts low. Very low. However, through a turn of fate, their luck incrementally rises into the good fortune sector. When the clock strikes midnight, though, the graph plummets back into ill fortune-nearly back to where it started. As for the ending, in Vonnegut's words, "the shoe fits and she becomes off-scale happy." The graph veers off into infinite good fortune. Shows that fit this mold are the typical family/Disney shows: The Sound of Music, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King, for starters. The protagonists start low, as outcasts and misfits, catch a glimpse of what happiness could look like, face intense trials, and eventually achieve ultimate good fortune.

4. "Kafka"

Planted squarely in the ill fortune sector of the graph, Vonnegut explains, "There's this rather unattractive, not particularly nice-looking, not very personable young man who has a really lousy job and disagreeable relatives. And, uh, so, it's time for him to go to work again...and he has turned into a cockroach." The Kafka narrative, according to Vonnegut, starts low and ends with infinite bad fortune. These are the shows that leave you thinking; the shows that affect you for hours to come. It's shows like Cabaret, Spring Awakening, and Sweeney Todd that fall into this category. Now, just because they follow the Kafka shape does not mean they are bad-or even that they are unpleasant. It simply means that these stories, while they have their funny and lighthearted moments, are meant to provoke a different kind of response from the audience. The ending of Cabaret, with its defiant dissonance, is a very different kind of ending than, say, Anything Goes. The audience isn't meant to tap their toes and leave the theater with a smile on their faces. They're meant to ponder-and ponder, they will.

Videos