Review: Learning and Losing at Love with HADESTOWN at Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts

In the name of true love, our warrior of words ventured into the underworld without a weapon in sight.

The most popular of tragedies often come with a warning, almost as if to tell the audience, "Step right up, come this way for heartbreak." The opening lines of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet pretty much serves as a spoiler alert for the story that will unfold. 1948's Letter from an Unknown Woman begins with a man receiving a letter whose opening lines are "By the time you read this letter, I may be dead." Likewise, 2001's Moulin Rouge! sees Christian already having lived through the events the audience has yet to see, only now finally putting pen to paper for our benefit. Hadestown, based on the millennias-old tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, prefaces the action with lyrics that tell us "it's a sad song, it's a tragedy... but we're gonna sing it anyway!"

This daring start helps bring the world of Hadestown to life by depicting how a celebration of life and a contemplation on death must always come hand in hand. The song remains the same, but its delivery changes based on the storyteller. Anaïs Mitchell's iteration of "Orpheus and Eurydice" sets the Greek tragedy amidst a parallel, steampunk version of mankind. As we come across a dingy café, we meet Hermes (Nathan Lee Graham), our emcee for the evening and somewhat neutral moderator to the goings-on of the world. He introduces the cast of characters ("Road to Hell") with particular focus on young Eurydice (Hannah Whitley) and humble busboy Orpheus (Chibueze Ihuoma). Their youthful infatuation ("Come Home With Me" / "All I've Ever Known") is countered by the faded love between Hades (Matthew Patrick Quinn) and Persephone (Lindsey Hailes). As Persephone leaves Hadestown for the world above, spring returns and the people celebrate ("Livin' It Up on Top"). However, she is still promised to him, and returns for long and harsh winters.

When winter comes, all the joy and celebration dissipates, with Eurydice wondering how she and Orpheus will get by. He is optimistic, having worked on a masterpiece he believes will entice Persephone to return to the world and bring back spring. This "Epic" gets revisited twice more throughout the musical, as he repeatedly refines it to perfection. But Orpheus' preoccupation with his music leaves Eurydice feeling forgotten. She gets enticed by Hades' empty promises of the wonders of Hadestown ("Way Down Hadestown"), eventually agreeing to sign her life to him ("Hey, Little Songbird" / "When the Chips are Down"). Although she calls out to Orpheus that she is leaving, he does not hear her - once more, he's too focused on his music to notice the world around him. Hermes tells Orpheus that she's gone to Hadestown, but gives him instructions how to get there freely if he wants to rescue her ("Wait For Me"). As Eurydice enters Hadestown, she sees it is nothing like the prosperity Hades promised, but she is trapped there ("Why We Build the Wall").

Unlike the traditional figures in Greek mythology, Orpheus is a hero, but not a warrior. He's an artist, but not a celebrity. He's a man, just a man, and one whose entire literary journey is focused on the love of a woman. Compared to Perseus or Achilles or Jason, Orpheus's tale almost always depicts how love drives him. Love of a woman, love of his art, love of the world. His armaments are not a sword or spear, but wit and word, as he weaponizes his songs to get what he needs. Throughout his journey into the underworld, Orpheus charms all those who may oppose them, appealing to their emotions and granting him favor. In the name of true love, our warrior of words ventured into the underworld without a weapon in sight. This optimistic, and perhaps naïve, approach to the archetypal Hero of a story truly makes Orpheus a fascinating figure, in both the original mythology and in Hadestown.

What draws the audience most to Orpheus, at least the Hadestown rendition, was how like most artists, he suffers a bit from Imposter Syndrome every now and then. The epic song he keeps tinkering around with always seems just short of being good enough for him. His neverending quest to get it right becomes a recurring theme in the musical. Eurydice leaves him for it, Hermes ridicules him, even Hades doubts it will be effective. Yet this eternal conflict of a talented artist has been portrayed wonderfully in both the book and the songs of Hadestown. The musical is a bit more on-the-nose about its message on climate change, with a bit of "eat the rich" thrown in. But I feel that the struggle of Orpheus, an optimistic and childlike dreamer, should not be overlooked. His own self-doubt at his greatness makes him a humble and admirable figure, but this very doubt will always play a part in his story.

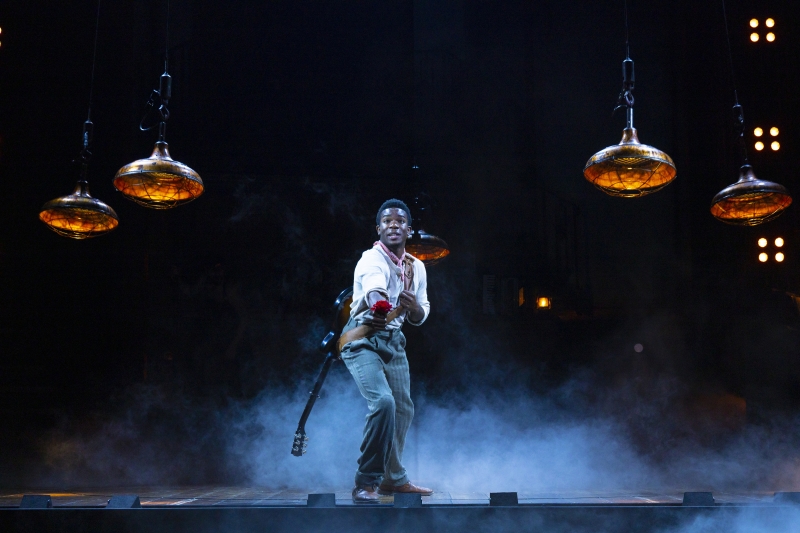

This is a character who, as everyone describes, has been gifted with the talent of music and song. They expect masterpieces every time he opens his mouth. Every song carries that extra weight of, "If it's from Orpheus, it must be good." To live up to that legacy would be daunting for anyone, but within the world of Hadestown, Orpheus handles it like a pro. We can credit much of this to portrayer Chibueze Ihuomo, who imbibes within Orpheus the gentle qualities that make him so beloved. His smooth, higher-register cadence also makes us believe that such a voice is both natural and God-given. The ease through which he emotes that seven-note "Epic" melody makes the composition feel like it truly must be the most beautiful music in the world.

Never mind that that melody has been heard before. For me, it's eerily reminiscent of both the opening notes to "The Bold and the Beautiful" and the plot-reliant music box of Tuck Everlasting. But my familiarity with the tune - even if it likely was not intended by the Hadestown team - helped paint a broader picture of Hadestown in its ethos of "we're gonna sing it anyway." Folks familiar with the story of Orpheus and Eurydice will already know how it ends. We know about the fateful turning point, about the outcome of his journey. And yet we relish every retelling of this tale, be it a Stravinsky ballet, a post-war arthouse French film, or an MTV-inspired Baz Luhrmann pop opera. Likewise, if Orpheus's seven-note "La, la-la-la, la-la, laaa" is reminiscent, it better drives the point home: the song remains the same. It's just a matter of enjoying who's singing it next.

The touring production of Hadestown resumed in 2021 after more pandemic restrictions were lifted. As it makes its way to Orlando, Florida during an unseasonably warm winter week, I honestly wished Persephone had already gone to visit Hades. This time last year, I was already comfortably wearing my red winter coat and driving gloves. Instead, I made do with putting on a light sweater over my polo as I walked over to Dr. Phillips Center.

My younger brother had seen the show in New York, so he filled me in on a couple of changes that the tour accommodates for based on the venue. For one thing, the entranceway to Hadestown is not the menacing garage-like doorway in the center of the café. On Broadway, a tiny lift is used to bring the characters below the stage. Having not seen the effect, I can't judge it, but a downward motion would certainly better sell the notion of heading into the underworld. Likewise, the entire set itself is smaller than the one currently in residence at the Walter Kerr Theatre. Even when expanded with those patterns of lights behind once Orpheus reaches Hadestown, there's still a crowded intimacy to that stage. The coziness is a better sell, as we're focused squarely on five major characters, the ever-present commentary from the Fates, and the five-person ensemble that represents The Rest of The World.

As mentioned earlier, Chibueze Ihuomo plays Orpheus, and does so with a gusto and innocence that made him an immediate favorite. Suffice it to say, on my drive home, I was slightly disappointed that the original Broadway cast recording doesn't have as much umph as Ihuomo's vocals. I've got nothing against Reeve Carney's recording (been a fan of his since The Tempest), but Ihuomo's vocals feel more at home for the character of Orpheus. Carney's voice has always been more "indie rock" for me than Broadway belter; Hadestown does have some beltable songs, but Orpheus's tracks often require a sweetness that Ihuomo conveys better.

Playing opposite of Ihuomo is Hanna Whitley as Eurydice. Whereas Orpheus is always portrayed as the innocent dreamer, Eurydice seems more grounded to the reality of her world. She's a tortured soul that is trying to survive any way she can. Whitley takes this characterization to the next level, offering a torn and regretful take on Eurydice. It's almost as if she's presciently aware every action she takes may be the wrong one, but that her soul is destined to repeat it again and again for the sake of Orpheus's story. There's a palpable sense of pain in Whitley's eyes every time she feels lost on that stage, every time she realizes her folly in following Hades.

Matthew Patrick Quinn's Hades could easily be a cookie-cutter charismatic leader. In lesser hands, Hades may very well have a large mustache that he'd twirl every so often in glee that Eurydice is doomed. But Quinn's approach offers, again, the hopefulness that a show like Hadestown gives to its audiences. At one point in the second reprise of "Epic," Quinn stands facing the audience while Ihuomo strums his guitar to sing The Masterpiece. At once, you can sense a great weight lifted from his shoulders when he hears "La, la-la-la..." Although the stage blocking is meant to dwarf Ihuomo behind Quinn, there was just a sudden shift to Quinn that signalled how he'd been turned.

For every Hades, there must be a Persephone, and Lindsey Hailes took on the role with a lot of what the late Kay Thompson would coin bazazz. Hailes' Persephone is larger than life, celebrating her homecoming to the world above as if it were the beginning of a beautiful block party. Yet, even when the role requires a more heavy, somber approach, Hailes knows to pull back and let the words of her own turmoil sink in. Hailes also can command the audience with just the tip of her finger, as she brought the thunderous, standing-ovation applause to a standstill at curtain call for one last song.

Of course, the life of any party in Hadestown is not in the two couples, but in the mischief and menace of Hermes. Nathan Lee Graham portrays the character with a playfully sadistic glee. His version of Hermes takes no sides in the narrative, but that won't stop him from enjoying it unfold on the sidelines. Watching Graham strut around throughout the story, one could sense he'd just as soon watch the world burn and opt to toast some marshmallows rather than put out the fire. Graham's sense of ownership across the stage made him a crowd favorite, similar to other "observatory" roles in theatre, like the Emcee of Cabaret or even Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Although one would expect the three Fates to have a larger role, Hadestown surprisingly gives them little to do beyond address the audience directly. Dominique Kempf, Belén Moyano, and Nyla Watson portray the three women, and their roles are a bit thankless beyond the songs that spell out their own criticisms of the story. I do understand their purpose in the story, but wish they were better written beyond the bridge between the two worlds.

Likewise, the ensemble players - Tyla Collier, Ian Coulter Buford, Courtney Lauster, J. Antonio Rodriguez, and Sean Watkinson - do double duty as both the citizens of the world and the indentured workers of Hadestown. Yet they're generally dispensable as characters. I did appreciate the fluidity among them when it came to dance partners, occasionally we may see Lauster and Collier in a two-step together, at one point Buford and Rodriguez wrapped arms as if they were old boyfriends. That sense of mixing and matching among the five provided a variability to their homogenized workers, all trapped as identity-stripped units of labor that must try to regain their individuality.

Of course, it's not the workers' fault that their characterization is little more than set dressing. We've spent the greater portion of Hadestown on a quest to rescue Eurydice. She becomes the focal point of our emotional journey with Orpheus. Rescuing her versus rescuing all of Hadestown is merely the identifiable victim effect of compassion fade; we're not made to care about the countless individuals lost to the town, just the one we've already come to know and love. But, sometimes, saving just one person is all we can endure and give of ourselves. Perhaps it's because Hadestown focuses on rescuing just one person that it's endured and found an audience. We can all empathize with that longing to bring back someone from our life that was gone too soon. Seeing the valiant effort of Orpheus to do so is just a way to forgive ourselves for not having that chance.

That likely wasn't the intent of the original Orpheus myth, but we're far enough removed from the original artist's intent that Anaïs Mitchell's rendition of "Orpheus and Eurydice" can live a healthy life without anyone decrying sacrilege to the text. As every generation may have their Hamlet, so, too, can we have our Orpheus. Hadestown reinvigorates the mythology by offering a contemporary criticism amidst the timelessness. The story has evolved and survived over time because of its message about love beyond death. For a modern audience, a simple story about love may not always be enough. Weaved into the tapestry of Orpheus's journey is also the effects of Persephone's shifting weather patterns because of her back-and-forth journeys into the underworld. Climate change was clearly not an issue in the B.C.E. days, yet the industrialization and progress of mankind has been a double-edged sword. The prosperity and ease with which we live our lives have long-term effects on the world that we can't always fathom. And, like Hadestown, we build and build and build toward a greater tomorrow that may never come.

Yet, our eyes are always on that horizon, looking forward to plant the seed of a tree we'll never climb, harvesting produce for a feast we'll never eat. As Orpheus reminds his friends in a toast, we are of two worlds: that which we dream about, and that which we live in. This optimism and hope serves as excellent counterpoint to the suffering of those working in Hadestown, because it points to a future that is more inevitable than the reality's cynicism may expect. End-of-days preparation and the death of civilization has been popular fodder for fiction. But the hope for a better tomorrow always outweighs these dark-times-ahead predictions, simply because it's a future better worth looking forward to. Hadestown knows this as it purposefully gives us a tragedy - one in which we know the ending - but also one in which we return to time and again with that hopefulness that perhaps, one day, it may change.

HADESTOWN plays at Dr. Phillips Center December 13 through 18. Tickets can be acquired online or at the box office, pending availability.