Review: THE KITE RUNNER Presented By Broadway In Chicago

The dramatic adaptation of a bestselling novel runs through June 23.

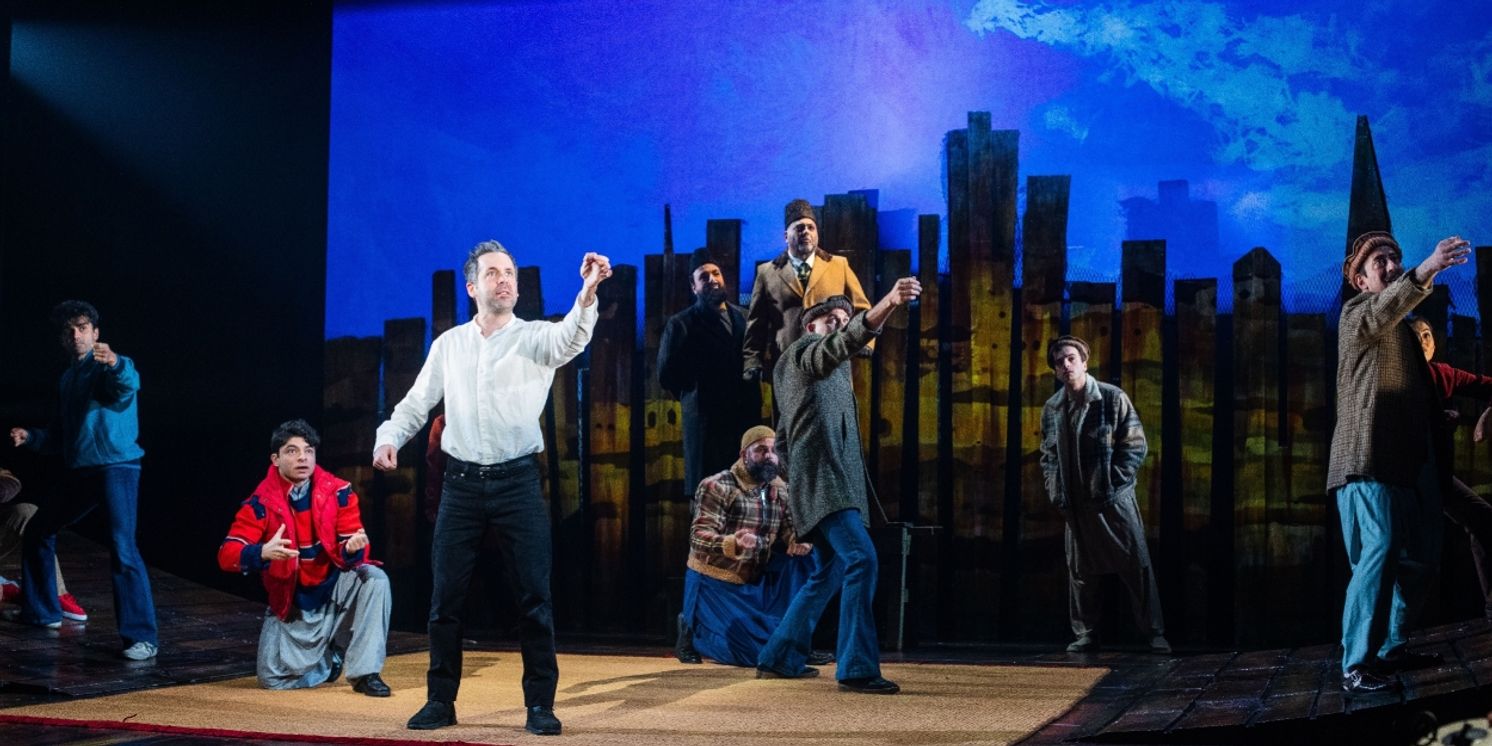

When Khaled Hosseini’s novel THE KITE RUNNER was published in paperback in 2004, it became an unexpected cultural phenomenon, soon selling well over a million copies and becoming the literary darling of book clubs across the United States. My high school required it as summer reading one year, and I’m sure many other teenagers of the 2000s had the same experience. Hosseini’s story of friendship and sacrifice was so powerfully affecting for readers that it was soon adapted for the stage by playwright Matthew Spangler in 2007. The dramatization has had a long road since then, receiving productions across the country in cities such as San Jose and Louisville, a West End premiere in 2016, and a Broadway run in 2022. Now producers are giving the play an even wider audience in the form of a national tour that has just landed at Chicago’s CIBC Theatre, running until June 23. Longtime fans of the novel may be enthralled at seeing the characters and events of THE KITE RUNNER brought to life before their eyes, largely through moving performances and clever stagecraft. But this dramatization feels unsatisfying, an adaptation that ultimately fails to convince audiences that it is necessary much less an improvement on the original.

Much like Hosseini’s novel, Spangler’s dramatic adaptation of KITE RUNNER tells the story of Amir (Ramzi Khalaf) and Hassan (Shahzeb Zahid Hussain), two best friends from different ethnic groups growing up in Afghanistan during the 1970s. Amir’s father Baba (Haythem Noor) is a wealthy merchant, and the two live in an expansive mansion while Hassan and his servant father Ali (Hassan Nazari-Robati) live in a “mud shack” further from the house. After a horrific act of violence against Hassan, an act that Amir fails to prevent, the two boys grow apart until the Soviet invasion of 1979 and the subsequent rise of the Taliban force Amir and Baba to seek safety in America. Amir spends the next few decades searching for ways to atone for his betrayal, even if it means sacrificing his life.

When adapting any literary work for the stage, the creative team must ask what their iteration can accomplish on the stage that could not be achieved on the page. In this regard, Spangler’s script and Giles Croft’s direction succeed on several counts. This dramatized version of KITE RUNNER gives audiences a much more concrete sense of Afghan culture and how it connects a community forced from their homeland. One of the second act’s more moving tableaus comes during a nikah, the Islamic marriage ceremony that unites Amir and his fellow refugee Soraya (excellently played with sweetness and strength by Awesta Zarif). In fact, one of the benefits of adapting this story for the stage is that it creates a greater sense of intimacy between the characters and the audience, bringing them into a time and place that risks feeling fantastical within the limits of the novel. Standout scenes include when Hassan lies to Baba about a stolen watch as a means of protecting Amir, and Amir’s hesitant courtship of Soraya.

Additionally, Croft’s staging makes use of a traditional Afghan tabla artist, a musician who creates music and sound effects using instruments native to Afghanistan and its surrounding regions. This production is lucky to have the virtuosic Salar Nader as its tabla artist, whose concentration and musical intensity always match the mood of the scenes he’s underscoring.

Within these scenes, Khalaf plays Amir as both an adult and a teenager, and he does so with careful nuance, never resorting to caricature as a child or melodrama as an adult. Spangler’s script makes Amir out to be more of a coward than the novel does, but Khalaf’s playfulness and sensitivity make the character refreshingly sympathetic. Amir’s actions are often inexcusable (at one point, he openly mocks Hassan’s illiteracy). So it’s a credit to Khalaf’s talent that his complex portrayal of a boy in unthinkable circumstances directly asks audiences, “Well, what would you have done?”

In a clever dramaturgical choice, Hussain not only plays Hassan but Hassan’s son Sohrab as well when Amir returns to Afghanistan a generation later. Like Khalaf, Hussain embodies the innocence and confidence of youth, with an added layer of fearlessness that has viewers rooting for Hassan even if he isn’t meant to be the hero of the script. Unfortunately, Sohrab isn’t quite as fleshed out, a fault that lies more in Spangler’s adaptation than Hussain’s performance. Hassan’s son, even in the novel, serves largely as a plot device whose existence is necessary for Amir’s ultimate redemption. But that doesn’t make Hussain’s performance any less moving when he desperately grasps for Amir as though his life depends on it—because it does.

Other notable performances include those of Noor, whose Baba has both the ferocity and protectiveness of a towering bear; Wiley Naman Strasser as the gleefully sadistic bully Assef; and Jonathan Shaboo as Rahim Khan, the dignified business partner of Baba.

But for all the talents of its cast and often inventive direction, this dramatized KITE RUNNER stands on shaky ground as an adaptation of a beloved novel that has sold millions of copies and been translated into scores of languages. Much of the play's action is narrated to audiences by Amir, but Spangler’s script frequently forgets the cardinal rule of “show, don’t tell,” sometimes attempting to do both simultaneously. This happens most egregiously when Hassan is tortured by Assef and his friends. The physicality of the scene is handled with delicacy and care, even as it conveys the boys’ horror and shame. But then Amir interjects to tell the audience the specifics of what had merely been suggested through Croft’s direction. At best, it feels as though the playwright doesn’t trust his viewers to trust their own eyes. At worst, it risks sensationalizing trauma.

And while smaller scenes between central characters feel palpably intimate, the grand historical sweep of the narrative feels virtually nonexistent. The invasion of the Soviets barely registers, relegated to the beginning of the second act and over within minutes. And one never gets a full sense of the horrors the Taliban has visited on their countrymen. Readers of the novel will vividly remember the soccer stadium scene, but that moment is only vaguely referenced by Assef. Obviously, there are limits to what can be shown onstage, and no one can walk into this production expecting something on the scale of LES MISÈRABLES. But this understanding only underscores how much this production, one perhaps begging to be done in a storefront or blackbox theater, gets swallowed up within the cavernous proscenium of the CIBC.

Nearly twenty years after its initial publication, THE KITE RUNNER and Spangler’s adaptation feel naively hopeful, barely more than a parable about the dubious triumph of good over evil. In what other kind of story can the Taliban be defeated without violence or bloodshed? Where else can an old friend have almost mystical knowledge that sends our hero on the path to redemption? But now, as the United States grapples with the many ways it has failed the people of Afghanistan, American audiences need more thoughtful, more realistic confrontations with this history and its reverberating consequences.

Reader Reviews

Videos