BWW Blog: The Problem with the Ingenue

What does it mean to actors and audiences when teenage female characters are automatically ingenues? And how can that trope be reimagined?

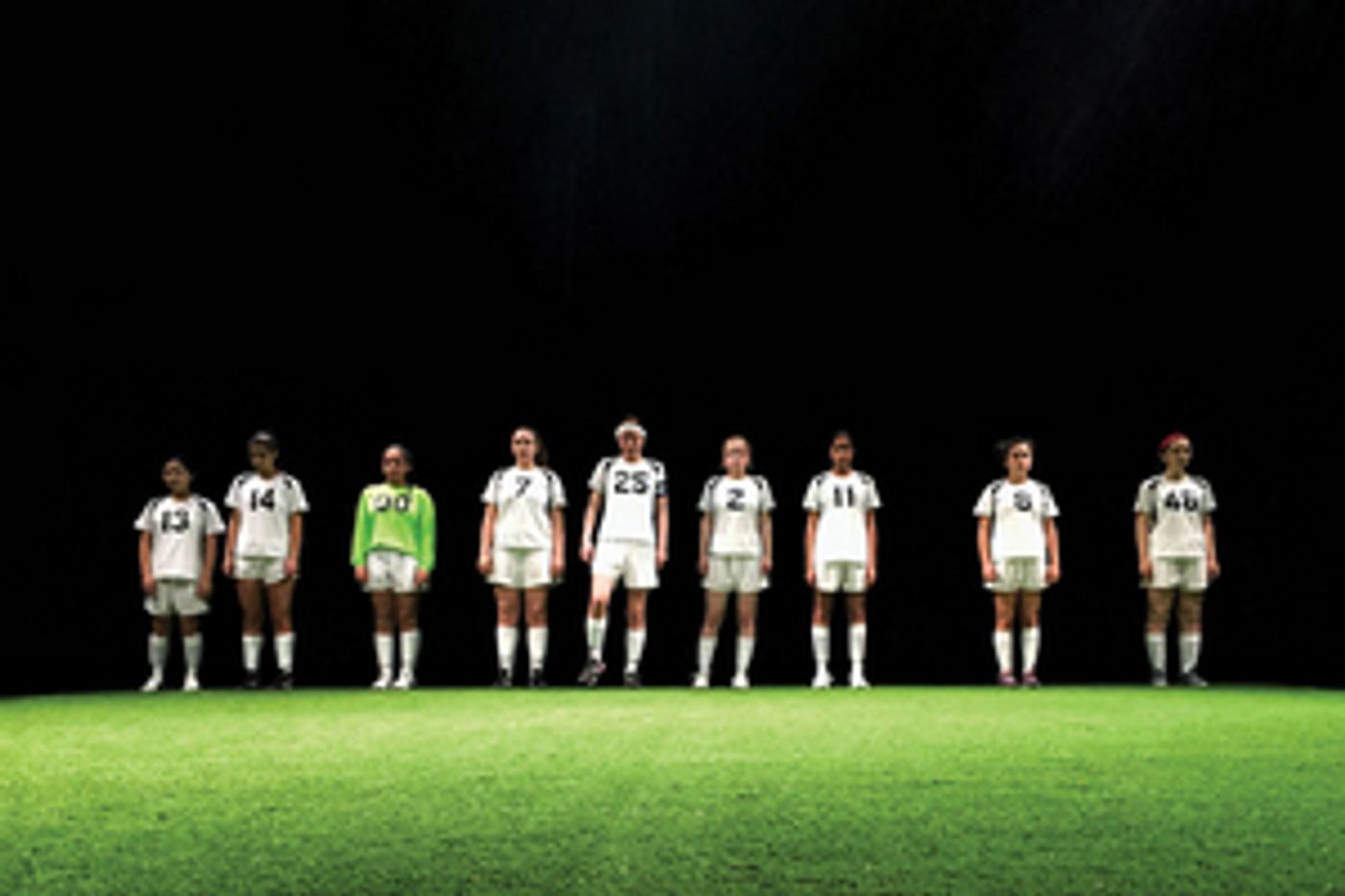

The Wolves (seen here in

Northwestern University's production)

transform the trope of the ingenue.

As I long for live theatre's return and sustain myself with memories of my favorite live theatre experiences, I keep coming back to Sarah DeLappe's The Wolves. The first time I saw the play, which follows a soccer team of 16- and 17-year-old girls, I was entranced. Breathless, on the edge of my seat, I knew I had discovered one of my new favorite pieces of theatre. The play followed me into my freshman year of college, when Northwestern produced it and I studied and wrote about the piece for a class. The more time I spent with the play, the more I came to realize just what made it so special to me: the teenage female characters of The Wolves were like almost none that I had ever encountered in the theatre.

When we see a teenage girl onstage, she is almost always an ingenue. In fact, the definition of the "type" almost stipulates it: according to The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, the ingenue is a character type appropriate for a youthful actress who portrays the female juvenile lead or the young heroine, and she must possess qualities of innocence and simplicity. The theatrical canon is rife with these characters: Juliet of Romeo and Juliet, Laura of The Glass Menagerie, Laurey of Oklahoma or Maria of West Side Story, to name a few. Though many beloved characters fall into this type, its prescriptive definition presents a problem: it stipulates that if a significant character is a teenage girl (e.g. if she is a female juvenile lead), then she is an ingenue. And if she is an ingenue, she is innocent, naïve, in love, and simple. Most theatrical writers have followed this prescription with hardly a question (and, historically, musical theatre has been especially guilty of this). While exceptions exist, they are not the rule. This logic, which ignores the fact that of course not all teenage girls match this description, fails to accurately represent the demographic and thus leaves a consistent suggestion that all girls fit (or ought to fit) this mold.

Such consistent depictions of teenage girlhood have consequences. As young women go through their formative years, they watch narratives constantly suggest that if a girl is thin, sweet, and patient enough, her turn will come for the fairy tale. This essentially unwavering ingenue story impacts expectations and sense of self, doing less than nothing to battle issues of alienation and depression so familiar to this very age group. And of course, the stereotypical representation of teenage girls as airhead idiots or sexual objects (something playwright DeLappe frequently discusses) does little to encourage the rest of the world to take teenage girls seriously - something clearly necessary in the age of #metoo when the vulnerability of teenage girls is being brought to public attention.

The pervasiveness of this archetype also shapes the experience of actors, whose "type" drives their pursuit of work. We are trained to identify our "type" (based on their age, appearance, personality, and vocal quality), to audition for roles that fit this type, and to dress, and perhaps even alter our appearance, to present most fully as this type. While older adult performers may have more options when choosing a type reflective of themselves, young (or young-looking) actresses auditioning at the professional level will generally be considered, simply by merit of their age and gender, for ingenue roles. Thus (with some variation depending on the context) this narrow type will prescribe everything from their manicured physical appearance to the types of songs and monologues they bring into auditions (which might be less than reflective of who these actresses really are).

As a young-looking college-age actress, when I audition outside of school I audition primarily to play teenagers, and probably will well into my twenties - so the teenage ingenue role is one with which I am painfully familiar. It's why I am so excited whenever I find the rare age-appropriate monologue that deviates into something more grounded, intelligent, or complex. It is why, especially as a young teenager in musical theatre, teachers coaching me to find my type crossed out most of my dream roles as far too old: the female characters that resonated with me, that had that groundedness, intelligence, complexity, and agency, were hardly ever the young women. It's why the title character of Anne of Green Gables was always so important to me, and why playing her a few years ago was so special: this intelligent, strong, grounded young female character could not be summed up in a few words, and never had I encountered a role (especially an age-appropriate one) that felt so true to me. And it's why encountering the young women of The Wolves was so thrilling: the play presents an entire cast of such real, complicated humans for young women to play. The playwright herself has said, "I wanted to see a portrait of teenage girls as human beings - as complicated, nuanced, very idiosyncratic people who weren't just girlfriends or sex objects or manic pixie dream girls but who were athletes and daughters and students and scholars and people who were trying actively to figure out who they were in this changing world around them. " DeLappe brilliantly paints this portrait with the universally compelling piece of theatre that is The Wolves. In doing so, she proves that questioning the trope of the ingenue and reimagining teen girls onstage is both very possible and very worth it.

I've become used to going into auditions and callbacks careful to look like the pretty ingenue: with the dress and heels, the carefully styled hair and the made-up face. Thus, to go into callbacks for The Wolves with a community of women all dressed appropriately for the show they are auditioning for with hair pulled practically out of the way, minimal makeup, sneakers, and real functional athletic wear (not even the feminine leotard and leggings one might wear to a standard dance/movement call) felt revolutionary: we were all there simply to be seen as our own full human selves. The Wolves transforms the playgoer's experience as well. It can do for a new generation of young female theatregoers what the Anne of Green Gables books did for me: validating the intelligence, strength, complexity, quirks and humanity of girls who have felt unseen by the typical depictions of themselves they've seen onstage. Its reimagining of the teen female character can deny the impulse to dismiss all teen girls as the same, instead telling the world that this is what teenage girls are really like - that they are remarkable individuals whom anyone can empathize with and be amazed and moved by.

This extended moment without normal theatre provides an opportunity to step back and look at our beloved art form from a distance, and to imagine how, as we work towards its return, we can rebuild it as something better than it was before. Perhaps this will involve a more critical look at the theatre's obsession with "types", like the ingenue, and the impact of these traditions. Our loving reminiscences on our most meaningful theatrical experiences can inspire us to ask: what were those moments that showed me not just what the theatre is, but what it can be? And how can those moments inspire further positive transformations of the art form?

Videos