Review: AWAKENINGS at Opera Theatre Of Saint Louis

World premier of new American opera at OTSL

"And what is so rare as a day in June?" Well, I'd say a soft evening in June--outside, on the lawn on the grounds of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, enjoying one's picnic and wine. It was most lovely. We had all come to see the world premiere of Awakenings. This is a work by composer Tobias Picker and librettist Aryeh Lev Stollman, and it's based on the book by Oliver Sacks.

OTSL is a world-class opera "destination", and it is renowned for its productions of new American operas as well as classics. Opera Theatre Saint Louis commissioned Awakenings for its 2020 season, but that production was delayed due to the pandemic. Now it arrives in the beautiful theater in the Loretto-Hilton Center.

Oliver Sacks was a neurologist--an Oxford alumnus who spent his career in America. He was a man with enormous empathy and a deep curiosity into the mysteries of the human brain, of which he was a keen observer. His brilliant essays help us understand these mysteries. He was a central figure in the world's growing acceptance of "neuro-diversity"--the concept that neurological anomalies are differences, not necessarily defects. Sacks died in 2015 at the age of eighty-two.

Dr. Sacks' 1973 book, Awakenings, describes his experience with twenty patients at a Bronx hospital who had survived the 1916 pandemic of encephalitis lethargica. They had been more-or-less asleep for decades. Sacks read of a new drug, L-dopa, and thought it might help such patients. He obtained permission to experiment with L-dopa on these twenty people. At first it seemed a remarkable success. Many of these patients, who had been nearly comatose, revived. They spoke, they walked, they even danced! But shortly strange side-effects appeared, and the patients ultimately relapsed into their old conditions of "sleep".

Dr. Sacks' book has been adapted into a movie, a ballet (by composer Picker), and a one-act play (by Harold Pinter). His study of the blind Molly Sweeny became a play by Brian Friel.

Many stars were clearly aligned to enable the birth of this new opera. Tobias Picker, who suffers from Tourette's syndrome, was a patient and friend of Dr. Sacks. Librettist Aryeh Stollman was also friends with Sacks. Stollman is a neuro-radiologist and is Picker's husband. So the creators have a deep understanding of this story.

But it's not quite a story.

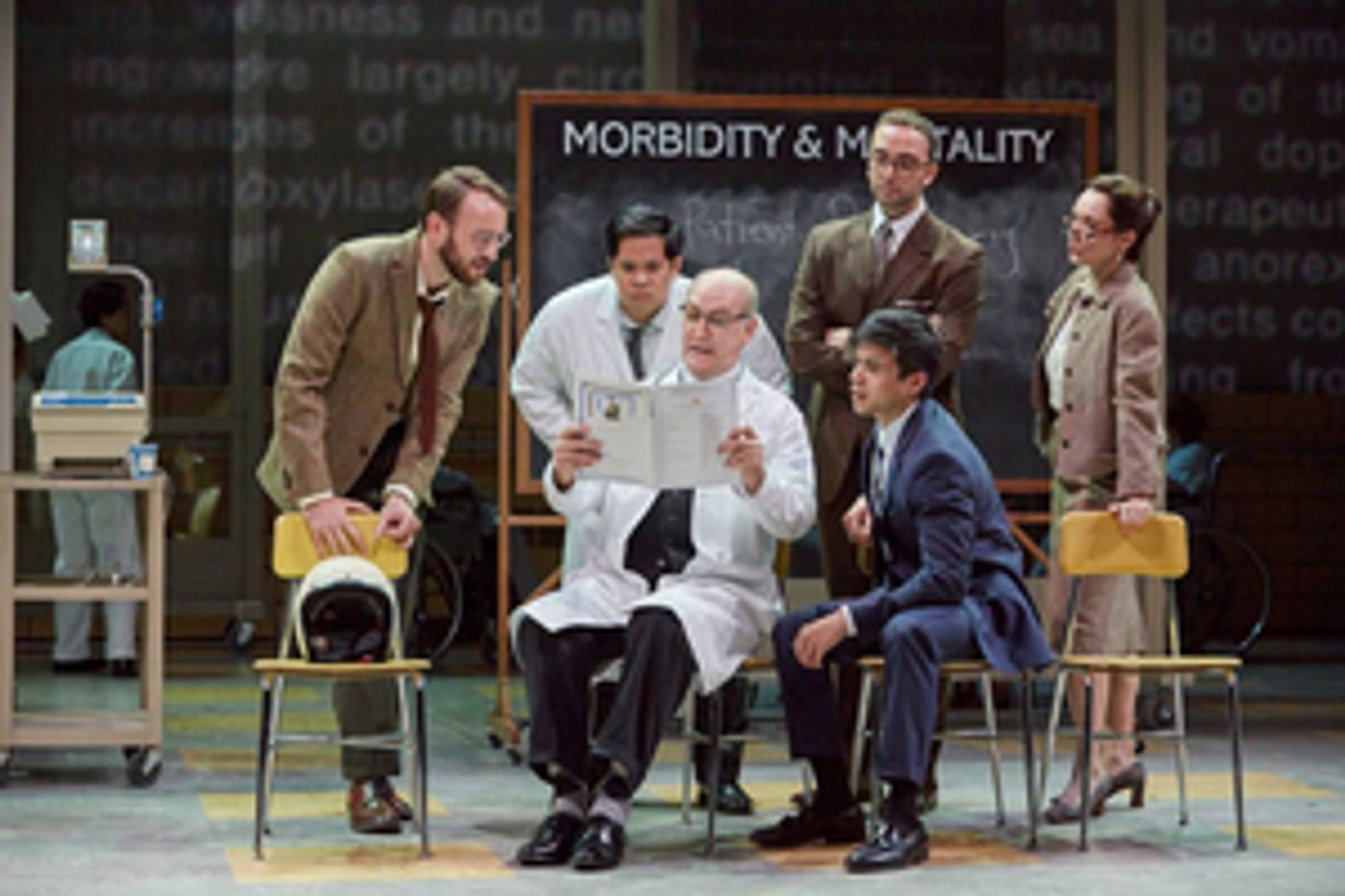

We enter to see a starkly simple stage. It's in a hospital. Six great glass panels on wheels provide partitions, and are moved nimbly as necessary to give patients' rooms, the day room, a botanical garden, etc. Nurses tend patients in wheel chairs. In the rear we have a couple of institutional radiators. Above and behind is a great projection screen, which will display the world outside: trees, the sky, a climatron. Images sometimes move strangely as befits the confusion in the minds of these afflicted people.

Much of the production team is exactly the same as for Emmeline, the Tobias Picker opera presented here four years ago:

Director James Robinson

Set design Alan Moyer

Costumes James Schuette

Lighting Christopher Ackerlind

Video projection Greg Emetaz

They work superbly together.

Librettist Stollman wisely chooses to focus on only three of the twenty patients--Rose, Miriam, and Leonard--who will adjust quite differently to their revival.

Dr. Sacks is sung by baritone Jarrett Porter, who conveys the doctor's deep empathy--even his love--for his patients. Porter has a fine rich voice, but at times, at the bottom of his range, his lyrics struggle with a slightly over-loud and busy orchestra. I found myself relying on the supertitles.

The Medical Director, Dr. Sack's boss and nemesis, is Dr. Podsnap. (How Dickensian!) This role is marvelously sung by bass-baritone David Pittsinger. He emanates power and authority.

Marc Molomot plays a patient, Leonard, who was snatched out of life at ten and now is middle-aged. His aging mother comes every day to read to him. Molomot has a lovely smooth, clear tenor voice-and we can understand every word. Leonard awakes to new and disturbing adolescent desires which seem most awkward--even embarrassing--in this middle-aged (and, we find, gay) man. Molomot handles these urges bravely.

Another patient, Miriam, is sung by soprano Adrienne Danrich. She gives a moving performance as Miriam meets her lost daughter and grand-daughter, who'd been told that she was dead. Miriam yields to self-pity, becoming maudlin as she wails about "all those lost years", but Ms. Danrich sings it all beautifully. Her duet with Rose--"What is time to us who choose to live inside our dreams?"--is simply gorgeous!

To me, the most engaging character is Rose, sung by Susannah Phillips. Ms. Phillips wrung our hearts as Birdie in Regina four years ago, and she win's us again as the sweetly optimistic Rose. Of all these patients it is Rose who most clearly calls out our emotions. She's always almost dancing as she dreams of her long-ago love. Rose is given some of the most listenable songs, and her warm and fluid voice makes them memorable musical moments.

Andres Acosta brings a stunningly lovely tenor voice to the role of Rodriguez, a male nurse. His duet with Leonard is another high-point of the evening.

Katherine Goeldner's very lovely voice and fine dramatic skills enrich the role of Iris, Leonard's mother.

Excellent chorus work is done throughout, from the soft opening, where they evoke the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty, to some rousing, even chaotic scenes, and to the closing, which brings us back to the gentle fairy tale. Kudos to Chorus Master Kevin J. Miller.

Music is varied, strong and interesting, though there is little real melody. Often there is a throbbing intensity down low in the orchestra as the voices float above it. Much seems atonal, and very much seems like recitative--little repetition, nary a rhyme. A lilting waltz or two are very welcome when they come. Conductor Robert Kalb leads members of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in a fine, dynamic performance.

But is Awakenings really a story--a dramatic story?

Overall it seems more like a case-history than a drama. The librettist wisely limits our main focus to three patients; he wisely allows them to interact with other patients (something which is absent from Dr. Sacks' book). Yet, still and all, none of these patients do anything at all that effects their fate. Things happen to them. They sleep, they wake, they rejoice, they fear, they sink back into their sleep. There is suffering along the way, but they make no dramatic choice. We never ask ourselves what these patients are going to do.

But is Awakenings really about the patients? Or is it about Dr. Sacks, the beloved friend of the creators? He made a choice, and his conscience ached when that choice went wrong. But Picker and Stollman are not content with that. They add a sad little romantic triangle: Leonard is infatuated with Mr. Rodriguez, the nurse. Rodriguez is infatuated with Dr. Sacks. And Sacks . . . ? Not in the market yet. It's almost Chekhovian: everybody's in love with the wrong person.

Of course none of this is in the book. Now Oliver Sacks was a famously shy, gay man. He certainly never wanted to be a famously gay, shy man. His reticence about making his erotic predilection public lasted until he mentioned that predilection in an autobiography a month before his death. Would he have been comfortable seeing that reticence made the very public central theme of an opera drawn from his book about suffering patients? And would he have made the tragic sleep of those patients a metaphor for his reticence? Perhaps not.

The romantic thing seemed very "pasted on" to me.

But Awakenings is given a very fine production at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis. Strange, exciting, often beautiful music, and wonderful voices. It plays through June 24.

For information visit Opera-STL.org

(Photos by Eric Woolsey)

Reader Reviews

Videos