Where Are All of the Female Theatre Critics?

Female playwrights sound off on critical interpretation of their work and the lack of powerful female critics.

In this, the second installment in our series on women playwrights, the playwrights speak about critical interpretation of their work and the lack of powerful female critics. Please read Part I here, which discusses the more general issues female playwrights face.

In 2002, Michele Lowe's THE SMELL OF THE KILL -- a comedy in which women debate whether to let their husbands die in a meat locker -- opened on Broadway. Critics, for the most part, were divided along gender lines. The majority of critics were men and they universally did not like it. The sole chief female critic at a New York daily, Linda Winer of Newsday, did, as did Roma Torre of NY1 and Pia Lindstrom of Fox TV. So, when women say the critical pool needs to be diversified, they speak from experience.

"On Broadway, women were calling out to the actors onstage, 'Don't let them out,'" Lowe told BroadwayWorld about her show, which closed after 40 performances on Broadway, but became tremendously successful regionally and internationally. "It was fantastic. Nobody had really put something up like this, where you didn't know what was going to happen to these men. The men didn't get it."

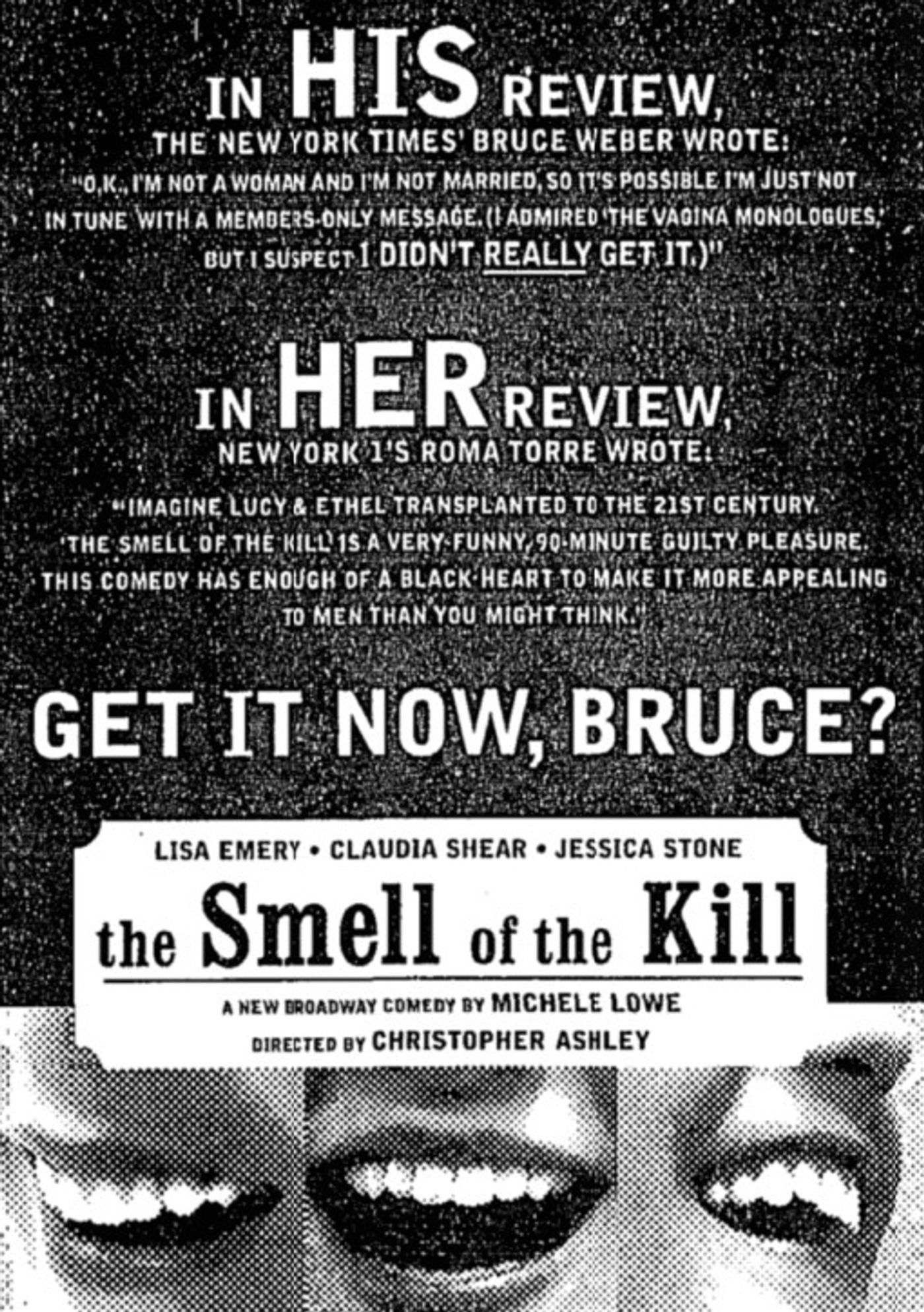

The split in critical interpretation would have escaped all but the most savvy consumers of theatrical reviews, but the production chose to highlight it in its ads. In a particularly scathing review, Bruce Weber, then The New York Times' second-string theater critic, called the show  "an 80-minute rimshot joke[.]" But then he said the part that is often the quiet part in reviews out loud; he wrote: "O.K., I'm not a woman and I'm not married, so it's possible I'm just not in tune with a members-only message. (I admired THE VAGINA MONOLOGUES, but I suspect I didn't really get it.)" The ad that ran days later in The New York Times led with the "O.K." line from Weber and directly below placed a quote from a positive review by Torre, with the kicker line (in all caps): "GET IT NOW, BRUCE?"

"an 80-minute rimshot joke[.]" But then he said the part that is often the quiet part in reviews out loud; he wrote: "O.K., I'm not a woman and I'm not married, so it's possible I'm just not in tune with a members-only message. (I admired THE VAGINA MONOLOGUES, but I suspect I didn't really get it.)" The ad that ran days later in The New York Times led with the "O.K." line from Weber and directly below placed a quote from a positive review by Torre, with the kicker line (in all caps): "GET IT NOW, BRUCE?"

Another ad for the show featured only female critics. Of course, female critics are not a monolith -- some, including Elysa Gardner of USA Today, did not like the play. But, overall, women critics liked it better. And there was something more subtle in the reviews, a point beyond the "yay" versus "nay" verdict.

"These male critics were vicious," Lowe, who has a new show premiering off-Broadway next season, stated. "The critic for The New York Times Westchester edition called me a 'man hater.' And he also said something about feeling sorry for my director that he had to work with me. It wasn't about the play. It went to me. That was really hard and awful."

Today, twenty years later, there is not a female head theater critic at any New York daily. The critics across the country are also predominantly white men.

Despite the fact that Ben Brantley chose one of her plays, A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY UNIT AT MEMORIAL SLOAN KETTERING CANCER CENTER OF NEW YORK CITY, as a New York Times "Critic's Pick," Halley Feiffer believes her work, and the work of other women, may be better received by a more diverse critical pool.

"We don't have the critical infrastructure set up to support plays that are by writers of marginalized groups, which includes women, and which might not appeal to the sensibility of the vast majority of major critics," Feiffer said.

This is not a new discussion. Women and people of color have been complaining for decades that the critical pool does not represent the population as a whole or the population of artists. Women in particular have questioned why, if the majority of Broadway audiences are women and the majority of ticket buyers are women (which both held true by a wide margin the last time The Broadway League released statistics), more of the tastemakers are not women.

For years, Winer, who left Newsday in 2017, was the only lead female critic in New York.

"Editors seemed comfortable having women be dance critics because that's men in tights and toe dancers and they didn't really care about it," Winer said. "Women could be off-Broadway critics, although seldom on staff, and that would be because it was mostly non-profit, and again culturally marginalized. It seemed to me if you were going to send someone to review an $8 million musical on Broadway, you needed to send a guy, because that was about money. I always wondered 'why.'"

The lack of female critics brings to light a few separate, but interrelated, issues. The first is whether works by women are treated differently simply because a woman wrote them. For example, if SMELL OF THE KILL was written by a man, that person would likely not have been called a "man hater." The second is whether the focus on women's issues or characters is viewed in a pejorative way by male critics. Some playwrights wondered if male critics could truly fairly review a piece of work not made to appeal specifically to them.

"Men have the whole society -- our society is built as a patriarchy -- and I do believe the higher up you are on whatever power ladder, the harder it is to see," Mfoniso Udofia, who said she does not read her own reviews, stated. "It's so difficult when the whole society is built around you and your gaze to understand that the reason why you might not like something is, it is not for you."

"That kind of power is like blindness and then from that point you can't really critique," Udofia added. "You're not listening anymore, because there's the assumption that it should be made for you and it should make sense to you."

Winer echoed this, noting it used to be that male critics were "shocked" when plays did not "talk to directly to them," but women were used to seeing male stories onstage and therefore were more likely to judge a property "with more empathy." She believes that still holds true to some extent.

In an unscientific review of over 200 recent reviews of major critics across the country, of works by both male and female playwrights, works by women appeared to indeed be treated differently. When plays are written by women, it appears that critics (particularly male critics) are more likely to speak about the playwright herself, her background, her activism, her familial relations. (Relatedly, features of female playwrights also mention their appearance more.)

Words used to describe the works themselves also feel gendered. Works by women are more likely to be called "cloying," "sentimental," "melodramatic," "cliched," "difficult," "emotional," "cute," "preachy," "overwrought," "bitter."

This past spring, Holly L. Derr, Head of Graduate Directing at the University of Memphis, examined, in an article on Ms. Magazine's online site, what she found to be gendered language in the review of Lauren Gunderson's The Catastrophist by Times chief theater critic Jesse Green. Derr criticized use of the following words: "Overwrought. Difficult. Coyly unstable. Unduly exotic. Cliched. Unseemly." (Green politely declined BroadwayWorld's offer to provide a response to this article or the broader question of sexism in his reviews.)

Reviews of plays by women are also more likely to discuss gender imbalance in the characters themselves. In other words, many reviews, including positive ones, will note the female characters in plays written by women are "more richly drawn" (to borrow one phrase) than the male characters. However, reviews of plays by men rarely note that the male characters are more fleshed out.

Gunderson, who has consistently been one of the most produced playwrights in America despite not having a New York hit, noted that some critics have heralded her plays. However, she also believes that numerous critics across the country have treated her work in a sexist manner.

"[It's] hilarious that in an artistic field all about evoking powerful responses and authentic emotion, so many male critics call it melodrama or dismiss it as overwrought," Gunderson stated.

This is also subject to counterargument. Perhaps, for example, plays written by women are more "sentimental" than plays written by men. That would follow stereotypical gender divides, the level of sentimentality in a work is highly subjective and the word is used to apply to works by male playwrights occasionally (Noah Haidle's BIRTHDAY CANDLES being one example). But there does seem to be something to these women's criticisms of criticism.

Feiffer -- who The New York Times' Alexis Soloski recently suggested might be a better librettist for THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA musical bec ause of her tendency toward "trenchant comic swings" -- explained that she does not believe she writes "the kind of women that men traditionally like to see [because] they have libidos, they use strong language, they have strong desires and they don't much care about men outside of getting sexual gratification from them."

ause of her tendency toward "trenchant comic swings" -- explained that she does not believe she writes "the kind of women that men traditionally like to see [because] they have libidos, they use strong language, they have strong desires and they don't much care about men outside of getting sexual gratification from them."

"I'm very open to, and eager to, receive legitimate critical response," Feiffer said. "But when the tenor of it seems to be for the most part: 'Why are these women so loud?' That reeks of misogyny and doesn't feel legitimate to me."

Unlike the majority of playwrights interviewed who said they did not read their own reviews, Feiffer has read them. "One critic called a play of mine 'catty,'" she said. "A play cannot be 'catty' from my understanding. I would be shocked if they called a play by Tom Stoppard 'catty.' I believe another critic called my play 'annoying.' I'm sure what they meant was something that felt completely legitimate, and probably is, but the language feels patronizing at best and sexist at worst."

Most women interviewed for this piece believe that a larger number of women in the critical pool helps. They recognize that not all women are going to like every work by a woman. In fact, many have had works poorly reviewed by women. They simply feel the more women, the greater chance their work will be judged fairly. (This is, again, similar to the arguments put forth by artists of color of both sexes.)

In 2017, when Lynn Nottage's SWEAT and Paula Vogel's INDECENT opened on Broadway, many women thought the negative New York Times reviews of the pieces felt gendered. Vogel and Nottage themselves blamed Brantley, Green and the patriarchy in tweets. Following this, a group of women playwrights conceived of the website, 3Views, under the umbrella of the Lillys, with the aim of offering reviews from a diverse set of voices.

The patriarchy flexing their muscles to prove their power. https://t.co/Zq5uzCxiUx

- Lynn Nottage (@Lynnbrooklyn) June 14, 2017

Tony-nominated playwright Sarah Ruhl, whose work has often been championed by Charles Isherwood and several other male critics, recognizes she "benefited a lot from reviews" early in her own career, but was still concerned about the critical landscape in 2017. "It was about the community," said Ruhl, who co-founded 3Views with Julia Jordan. "It felt particularly awful to the community of women playwrights that particular year. As a teacher at Yale School of Drama, seeing young playwrights come into the field in New York, particularly if they were playwrights of color, I worried they would feel unseen."

However, Ruhl, currently represented off-Broadway by BECKY NURSE OF SALEM at Lincoln Center, now feels more optimistic about critical culture.

While Green, a white male, is the chief theater critic for The New York Times, there is now a large roster of female theater critics there. Of the 16 new straight plays that have opened since the pandemic, Green has reviewed 10, but Maya Phillips has reviewed four, Soloski one and Laura Collins-Hughes one. If you include play revivals (and exclude the remountings of SLAVE PLAY and TAKE ME OUT), Green has reviewed 17 plays, Phillips seven, Soloski two and Collins-Hughes two. (Former New York Post head critic Elisabeth Vincentelli also reviews for the paper. Additionally, Nicole Herrington has been editor of the theater section since 2020, replacing a man in that role.) That is a far cry from twenty years ago when Anita Gates was the only regularly-appearing female theater critic at the paper of record, and she rarely reviewed Broadway. Helen Shaw is a critic at The New Yorker. Marilyn Stasio is still entrenched at Variety. There are various women reviewing for websites. The website DidHeLikeIt.com -- which was launched to feature the reviews of then Times chief critic Brantley with a "Ben-o-meter" -- is now DidTheyLikeIt.com and features a variety of critical voices. Last season, there were five female members out of the 22 voting members of the New York Drama Critics' Circle, whereas decades ago there were none or one. (One of those five women is a woman of color, one of only two people of color. Times critics are not generally permitted to be members.)

No playwright spoken to said that only women should be sent to review plays by women. And clearly men will not necessarily dislike a show by a woman. For example, Green's rave review of the off-Broadway production of Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu's PASS OVER, a play by a black woman about racial dynamics in America, was partially responsible for the show's transfer. He then raved about it again on the Great White Way. (While that show did not have female characters, he also lauded Broadway productions of Lynn Nottage's CLYDE'S and Morisseau's SKELETON CREW last season, which both did.) But there is something to making the pool more heterogeneous, even within one publication. For instance, let's say, a show seems to have women as its target audience, but a male Times critic initially reviews it negatively, that same show might also later be included in a "Critic's Notebook" written by a woman.

"I think The New York Times has made a real effort to diversify their pool," Ruhl said. "I can see them really thinking about who they send to particular shows. And I think there are a lot of organizations that are developing young voices of critics and really trying to nurture women and critics of color."

But some are less hopeful for various reasons. First, they question why The Times could not elevate a woman to co-chief theater critic, a title Green shared with Brantley for a few years before Brantley retired. Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott have been co-chief film critics at The Times for years.

"My production received an amazing review from Laura [Collins-Hughes] and I'm so grateful for it," one playwright, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said. "But I was hopeful for a transfer, and I was told it wasn't enough, because she wasn't a Green or a Brantley. There has to be a way to tell people other Times reviews are important."

Second, they worry that until there is a truly complete critical diversity, one or two women will have too much power. If, for example, one major female critic reviews a project geared toward women and does not like it, that will then an outsized impact on that property.

Third, some argued that increasing diversity numbers was not enough.

"A male critic versus a female critic, a white critic versus a critic of color, the outer optics are just optics," two-time Tony nominee Dominique Morisseau said. "The mentality is what I question. You can look like whatever. I know people say 'representation matters,' and it does, but it's not all that matters."

Morisseau noted we all uphold the patriarchy in our own way: "You take a black woman  critic, I'm a black woman. That does not mean that they cannot uphold, or even that I cannot uphold, tenets of white supremacy in my work. Because I'm black it doesn't mean I'm free of any residual baggage of being a part of a white supremacist patriarchal culture. I'm not free of that. No one person can be the solution. So, for me, I'm not interested in reviewers just changing optics. I'm interested in changing the whole system of operations."

critic, I'm a black woman. That does not mean that they cannot uphold, or even that I cannot uphold, tenets of white supremacy in my work. Because I'm black it doesn't mean I'm free of any residual baggage of being a part of a white supremacist patriarchal culture. I'm not free of that. No one person can be the solution. So, for me, I'm not interested in reviewers just changing optics. I'm interested in changing the whole system of operations."

Morisseau and others argued that the current critical structure operated to "oppress and depress," as one termed it, artists. (They especially worried about harsh criticisms at this point in time, with theater still not back to pre-pandemic normality.)

"The press and theater should be in conversation with each other and asking the public to weigh in," Morisseau said. "If it functions differently, it can invite people to the conversation. It could be: 'I had this experience of this show. What would you see if you came to see it? Come, weigh in and let's talk about it.' Not 'let me kill that show from ever seeing the light of day.'"

That is sort of the way 3Views functions. The site is not people writing overnight reviews -- each month three writers focus on a piece and reflect on what that piece means to them. 3Views also has artists commenting on work and the times we live in.

"There's an aesthetic shift in it as well as the question of multiplicity, a different kind of writing about theater," Ruhl said. "I think that it is quite different, having almost reader response pieces, where you might be writing about a really personal memory as it relates to a play you've seen."

The New Yorker's Shaw is a 3Views fan, believing it adds to the critical conversation.

"There are a lot of different forms of theater and there are not that many forms of criticism," Shaw said. "If you read about criticism in the 60s, we actually had a few more forms. We had a public essay culture. There was the difference between a Sunday and a daily critic. There were TV critics. And we seem to have been in a kind of long diminuendo of people being inventive about how to cover the field, even when the field itself is getting very inventive. So the thing I love about [3Views] is it is genuinely the first group I've seen who have experimented not just with point-of-view but also with form."

While this is all well and good, and people in the community or devoted theater fans may enjoy these additional forms of analysis, most (though far from all) playwrights interviewed believe that it will not be a substitution for traditional criticism. The reason we have been going through a diminuendo, which BroadwayWorld has written about previously, is that it is hard to get eyes on most theater coverage; dedicated theater critics have been laid off throughout the country. (As Winer remarked: "When we finally got women, nobody cared about critics anymore.") It therefore seems unlikely that the vast majority of ticket buyers will read more expansive coverage of the theater. Instead, they will be looking to be quickly guided in purchases.

"Most people look to critics in all fields to tell them what to read, watch," one playwright, who requested not to be named, stated. "2022 theater can't lead a societal shift in America."

Gunderson, who has been victim to the one critic per city system in various markets across the country, also believes in critics.

"I do believe that if we had more critics, not less, that represent a much broader perspective, lived experience, and variety of tastes and aesthetics that the whole field and everyone who loves it would be so much better off," she posited.

Please read the final installment of this series here.

Author's note: None of these issues are easy issues, particularly in the world of intersectionality, in which multiple factors (sex, gender, race, religion, appearance and more) factor into how you are treated. Additionally, in this piece, the art itself is different. Feel free to reach out to me at cara@broadwayworld.com if you would like to discuss any of the topics raised in this piece.

Videos