Student Blog: From Page to Stage: Dramaturgy in Munich

The role of research and context in Antigone in Munich.

When my school’s fall play was announced in May, my peers and I were ecstatic. In October, we will be performing Claudia Haas’s Antigone in Munich. Our first readthrough was last week, and I can already tell what an exciting project this is going to be. The plot revolves around Sophie Scholl, who was part of the White Rose Society in Nazi Germany, a group that promoted passive resistance against the oppressive regime. Antigone in Munich tells the story of her transformation from bystander to witness to activist, inspired by Sophocles' Antigone, which asks, "What do you do when the laws of man go against the laws of God?" For this show, I will be playing the role of her brother, Hans Scholl. Hans is the one who gets her involved in the movement and is a large part of her life. I am also on two technical crews, Publicity Crew and Dramaturgy Crew. I, partnered with a close friend of mine, submitted a scenic design for consideration as well, but the panel ultimately decided to go a different direction.

Prior to being cast as Hans, I had already been assigned to research him as part of my duties as a dramaturg. Naturally, as soon as I found out I would be playing the role, I consumed every piece of media related to him and his life that I could. I’ve read countless letters written by him and his friends, diary entries, interrogation transcripts, and more. My goal is to gain a complete picture of his life to the best of my ability, so that I can then apply Adler and Stanislavsky’s techniques in order to become him. This might seem like a lot for a high school fall play, but, as someone who is trying to go into this craft beyond high school, I need to absorb all the knowledge I can while I can. What picture of his life have I acquired? Well, let me tell you.

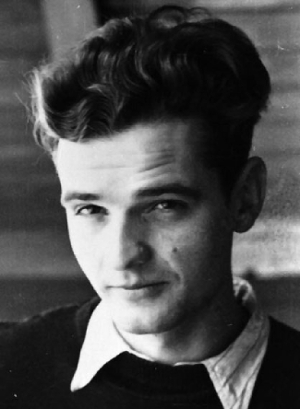

Hans Scholl was born in 1918, the second child in a liberal German household. Following World War I, his father was the mayor of a small German town called Forchtenberg, located in the center of the triangle of Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Nuremberg. His father was an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime as Hitler began rising to power in the 1920s, and would later be forced to resign from office. In 1933, at age 15, Hans joined the Hitler Youth, much to his family’s displeasure. Hans saw the group as a social organization for young German patriots, and even became a Fähnleinführer (platoon leader). However, further into the decade, as legal action against his father became more pressing, Hans began to become somewhat disillusioned with the National Socialist way of life. The irony in the fact that Han’s disobeyed his father’s wishes to join a political group that he would later die to speak out against really sticks out to me here. From an early age, Hans was considered to be very charming. It is fascinating to consider the idea of a less social Hans who evolved during his time as a Hitler Youth member to blossom into the attractive young revolutionary he would become known as.

Speaking of Hans’ attractiveness, his first serious relationship beyond the various girlfriends of his boyhood was not a girl at all. In 1934, Hans befriended another Hitler Youth boy named Rolf Futterknecht. By 1935, the two were in a romantic relationship that would last well into the following year. In 1936, in addition to remaining active in the Hitler Youth, Hans created a social group for boys based on the principles of the German Youth Group for Boys of November 1, 1929 (more commonly known as dj.1.11). The original group was an anti-bourgeois movement that formed in response to the industrial age in the early 20th century, but whose ideas clashed too much with Naziism by the late 1920s. When Hans reignited the group in 1936, it focused more on camping and hiking than political or economic discussion. Rolf joined, as well as Hans’ brother Werner and their neighbor Ernst Reden. One key principle of the original dj. 1. 11 that Hans didn’t seem to mind keeping alive was the group’s homoerotic behaviors. Ernst and Werner had a brief relationship, but Werner stopped reciprocating Ernst’s pursuits quickly. In spite of this, under the watchful eye of the Gestapo, Hans and Rolf broke off their relationship sometime in 1936, likely sometime around their departure from the Hitler Youth program. Hans continued activity with dj. 1. 11 as he began his state-mandated labor in 1937, a newfound wave of crackdowns on Nazi anti-homosexuality laws (the infamous Paragraph 175) from 1935 finally made its way to dj. 1. 11. The group was taken into custody in late 1937, along with all of Hans’ siblings, including Sophie. Over the next few days, all of the Scholl siblings except Hans would be released. Hans was held and interrogated until early 1938, tried under Paragraph 175 along with Ernst. He hadn’t even known that same-sex intimacy was a crime, or so he claimed in his Gestapo interrogations. Nonetheless, he admitted to continuing his relationship with a “special friend,” the younger Rolf Futterknecht, for nearly two years. He described it to the Gestapo as “an overpowering love … that required some means of relief.” The Gestapo transcripts reveal remarkably candid testimony in which Hans strove to justify himself while protecting Futterknecht. “I am inclined to be passionate,” Hans said. “I can only justify my actions on the basis of the great love I felt for [him].” Later in the interview, Hans added, “I can hardly comprehend my behavior today.” At one point, he even claimed to have raped Rolf, not knowing that Rolf’s testimony was already entirely to the contrary. The judge cited Hans’ exemplary record, a general amnesty for members of illegal youth groups and the many strong testimonials offered in his defense, ruling that the teenager’s same-sex relationship had amounted to an adolescent aberration. Ernst, however, was found guilty and sent to a concentration camp for six months.

It’s no wonder that, as a bisexual man, the part of Hans’ life where his sexuality plays such a large role is so fascinating to me. His older sister, Inge, who wrote the first account of the White Rose Society’s resistance, left out any explicit mention of anything having to do with this time in Hans’ life. It is likely that only she and their parents knew of it. There is an innate desire to understand that which history would rather one didn’t, and nowhere is that idea more clear than in Hans’ relationship with Rolf. It’s tragic and unfortunate, but there is only so much that will ever be truly known about it.

In 1939, Hans was discharged from labor to study medicine at the University of Munich. He began a relationship with Anneliese Graff, through whom he met future White Rose member Willi Graff. He was sent to the French frontlines as a medic after only a semester, furthering his hatred for the war. He served there for two years. In 1941, back at the university, Hans met students and future White Rose Members Alex Schmorell and Traute Lafrenz. Over the summer, he and Traute were lovers for a while before deciding to just be friends. Traute Lafrenz, explained to historian Dr. Robert Zoske that the couple broke up as Hans had a deep problem that he kept “dreadfully secret.” Traute refused to say what this problem was, but both Zoske and historian Jud Newborn believe that she was referring to Hans’s sexuality and much like Inge Scholl, she was afraid that being known as homosexual would destroy Hans’s legacy. Hans later became romantically involved with Dora Fabjan and then Rose Nagele and Kathe Hebrecht. It’s possible then that Hans was either trying to hide his homosexuality by using these girls as a cover, or that he was once again trying to become ‘clean’ of his sexuality. It’s equally possible that Hans was bisexual. Before the end of 1941, Hans and Alex were sent to the Russian and Polish fronts as medics. On top of his father’s influence, his political group from his teen years, a second conscription, and a humiliating criminal trial for being in a queer relationship as a sixteen-year-old, the horrors of the Battle of Stalingrad proved to be Hans’ final straw when it came to the Nazi regime.

Upon returning to Munich in 1942, Hans and Alex founded the White Rose Society: a non-violent resistance group. They opposed the Nazi regime through a series of anonymous leaflets and graffiti, calling for active opposition to Adolf Hitler's dictatorship. The group emphasized moral and ethical resistance, advocating for the preservation of human dignity and freedom in the face of totalitarianism. They wrote the first four leaflets, which were left in telephone books in public phone booths, mailed to professors and students, and taken by courier to other universities for distribution. Hans and Alex were sent back into the service, for Hans’ third go-round, in Russia. Once they got back, Willi Graff joined the White Rose, followed by Sophie Scholl and a Professor Huber. Hans was initially reluctant to involve his sister, for her own safety, but he could not hide his movement from her forever whilst they were living together. In January 1943, he began a relationship with Gisela Schertling, who was oblivious to the actions of the White Rose Society. However, this would be short-lived. Two more leaflets were circulated by the White Rose, and Hans and Sophie were arrested after being caught by a custodian while distributing the sixth at the university.

During his interrogation, Hans Scholl tried to protect his sister by claiming he had thrown the leaflets himself, but his testimony was contradicted by the custodian. He also attempted to shield the involvement of other White Rose members. After several days of interrogation, Hans and Sophie were tried and sentenced to death. Their parents tried to attend the trial but were forcibly removed. Instead of the 99 days they were legally supposed to have before execution, they were told they would be executed that same day. In prison, they wrote final letters and were prayed over by the prison minister (as described in The White Rose by Inge Scholl). Hans' last words to his parents were, "I have no hatred. I have put everything behind me." His father replied, "You will go down in history. There is such a thing as justice." Hans, Sophie, and another member of the White Rose who had been sentenced to death, Christoph Probst, were placed in a room together, where a guard, breaking the rules, gave them a cigarette to share as they awaited death. Sophie was the first to be taken to the execution room. Hans followed, shouting "Es lebe die Freiheit!" ("Long live freedom!") as the blade came down.

While the events of Antigone in Munich focus primarily on Sophie's role in the White Rose Society and her growing disillusionment with Nazism, understanding the circumstances at play in Hans’ character is going to be key for me in portraying him well. The only other real-life person I have gotten to play thus far is Buck Barrow in Frank Wildhorn’s Bonnie & Clyde, and I wish that I had had the understanding of dramaturgy that I do today a few years ago, so that maybe I could have done Buck a bit more justice. I am beyond excited to take this work into the rehearsal process for Antigone in Munich, running October 24th - 26th!

Sources:

- "Hans Scholl"

- "Weimar Youth Groups"

- "Hans and Sophie Scholl Were Once Hitler Youth Leaders"

- "Traute Lafrenz"

- "Hans Scholl (The Historian's Magazine)"

- "The Three Trials of Hans Scholl"

- "Hans Scholl Skiing with Rose N."

- Hans Scholl re: Gisela Schertling

Comments

Videos