Review: GIANT, Royal Court

New play on the much loved author's antisemitism delivers less than it promises

A jarring moment last year in the popular BBC2 quiz show, Only Connect. Host, Victoria Coren-Mitchell, took time out from self-deprecatory remarks about her boozing and gentle jibes at the nerdier contestants to call out Roald Dahl as an antisemite. A national treasure accused of a hate crime by a soon-to-be national treasure in a pre-recorded parlour game the lawyers must have seen? And then a few memories stirred - the writing shed, the wartime flying and, yes, there was something else wasn’t there?

A jarring moment last year in the popular BBC2 quiz show, Only Connect. Host, Victoria Coren-Mitchell, took time out from self-deprecatory remarks about her boozing and gentle jibes at the nerdier contestants to call out Roald Dahl as an antisemite. A national treasure accused of a hate crime by a soon-to-be national treasure in a pre-recorded parlour game the lawyers must have seen? And then a few memories stirred - the writing shed, the wartime flying and, yes, there was something else wasn’t there?

Some scandals stick and some don’t and there are many reasons for that, some by design and some by default, but it’s good to be reminded of the darker places in the souls of some artists. Whether one does anything with such information - say avert your eyes from the Caravaggios and Modiglianis in galleries, burn your Neil Gaiman books or dump your The Godfather DVD boxed set in the recycling - is your decision… if the cancellers of the Right and Left haven’t got there first.

We don’t require any temporal contextualising of Dahl’s antisemitism, no sensitive parsing of the terms Zionist, Israeli and Jew, no quasi-medical offsetting against mental health issues - it’s just there, googlable, unabashed, disgraceful. It’s there in the celebrated stories too, but you do need to go looking and there’s much else wrapped around it. And don’t forget that kids, spending as much time as they do in happy, unhappy and fractured families, are pretty good at understanding the complex interactions of good and evil within individuals and across groups.

Mark Rosenblatt’s new play, Giant, his first after a long career directing, takes us back to the source material, Dahl amplifying his antisemitism in writing and in conversation. It starts ugly and stays ugly - a tonal issue the play, even under Nicholas Hytner’s direction, never resolves, hobbling its dramatic potential.

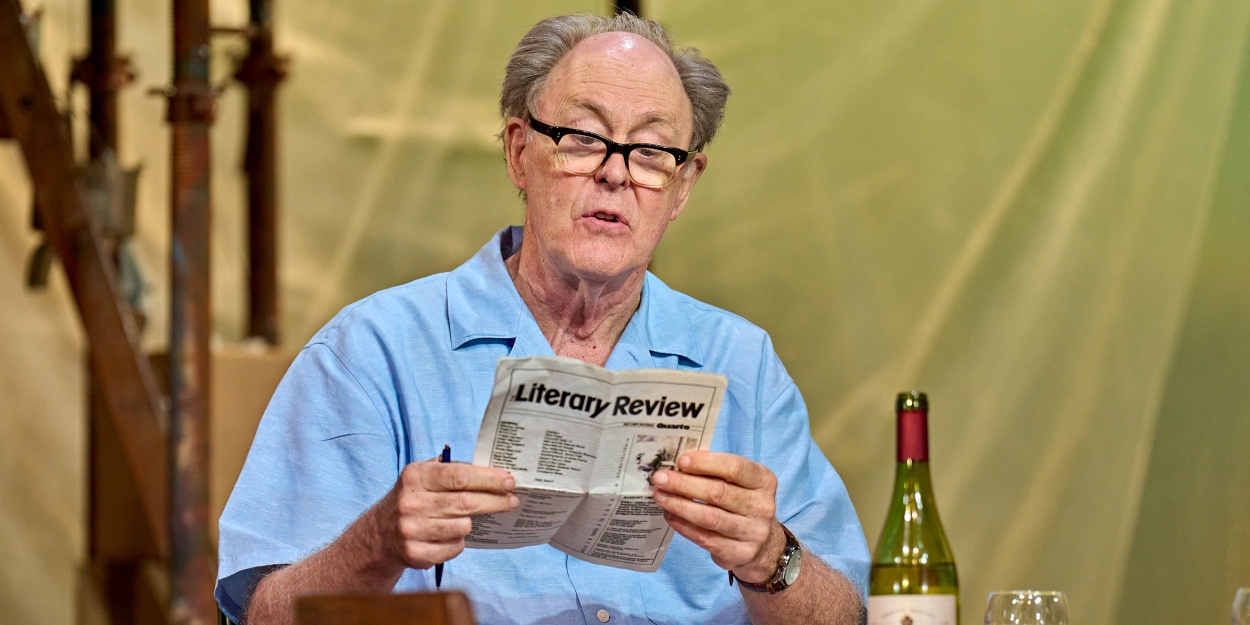

It’s the summer of 1983, Dahl is in his mid-sixties, recently divorced, suffering back pain, confined to one room in a house undergoing renovations and fretting about the launch of his new book, The Witches. He’s indulged by his fiancee, Liccy, waited on by his maid, Hallie and fawned over by his publisher, Tom. His ego sits atop this metaphorical throne and radiates entitlement. Naturally, the only person he really seems to like for their own sake is his gardener, Wally, who has known him for decades and whose muddy boots complement his employer’s feet of clay.

Until a visitor, Jessie Stone, arrives from New York with a request, nay requirement, from his US publishers, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, to apologise for a virulently antisemitic book review he recently wrote for the Literary Review. He won’t of course, citing the book’s subject - the Lebanon War of 1982 - as justification for his anger and his allocation of blame, and things go from bad to worse.

It’s an imagined meeting of course, but the bedrock of the play - Dahl’s shocking words - are drawn directly from sources. That does beg the question as to why so little of the plot rings true. Would FSG’s representative, with a superstar writer’s contract at stake, be so underprepared for a man who never hid his (let’s be generous) irascible personality? Would his long-time friend and UK publisher be so incapable of effective intervention as things spiralled out of control? Would the maid really storm off after overhearing opinions on a self-sabotaging phone call she must surely have heard before? The reality sniff test was not passed for me.

That’s no fault of the actors, who do all they can with this flawed set up. John Lithgow has Dahl’s look, his wisecracking charm, especially in the first half in which his more outrageous statements seem a little bit naughty rather than nasty. It’s no easy task to suggest sensitivity under the carapace of so unattractive a personality, but he does, catching the writer’s genuine distress at the fate of victims of the 1982 invasion. Lithgow also finds the glower of the true believer, as darkness descends after the interval.

Romola Garai, when Mrs Stone is not repeatedly running away in unlikely tears, stands her ground well as something of an emissary from 2024’s less tolerant approach to the causing of offence. She has more to bite on than Rachael Stirling’d Liccy, trying and failing to control Dahl like a supply teacher with an unruly schoolboy. Elliot Levey gets some laughs as Tom Maschler, but I just didn’t buy his acquiescence in the role of Dahl’s punchbag - it did not square with the urbane, pragmatist who had navigated life so successfully for so long.

A flawed play then, but one that at least tries to address thorny key issues of the day in politics and art. Will it, as the best theatre should, change minds or, if that is too much to ask, at least challenge mindsets? That question is subjective and in the eye of the beholder, but I doubt anyone seeing the play will turn on the radio the next morning to hear of more carnage in Gaza or Southern Lebanon and form a new view on its origins or its potential outcomes. Nor do I believe anyone will see Matilda, Charlie or James any differently, nor even the infamous Witches either.

Maybe a parent or two might offset the thirst many kids develop for Dahl with some of Charles M ‘Sparky’ Schulz’s Peanuts cartoons. And that would be a good thing.

Photo image: Manuel Harlan