BWW Blog: Creating Theater That Fully Embraces the Virtual Format

The most successful virtual theater I have seen this summer had a clear awareness of the virtual format and its limitations, realities, and capabilities.

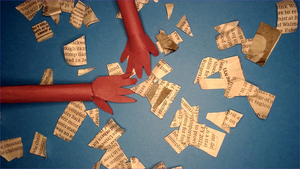

virtual production "a farm for meme."

Puppetry design by Katharine Matthias.

When this pandemic started, my initial reaction to virtual theater was fairly skeptical. I love theater because it is a live, shared experience between artists and an audience. It is almost impossible to recreate that experience, and that exchanged energy, virtually. I don't necessarily think that the theater community should try to recreate live theater. Instead of recreating something that will always be better live, in a crowded theater, perhaps artists should embrace the new opportunities and resources that come with the virtual medium.

The most successful virtual theater I have seen this summer had a clear awareness of the virtual format and its limitations, realities, and capabilities. For example, I helped create a devised theater piece through the Hangar Theatre's Lab Company this last June. It was part of their Wedge series, and the piece was written entirely by the group of young artists in the program. In the end, I was incredibly proud of the ways the piece embraced the Zoom platform we were on. Scenes between actors were written as Facetime calls or Zoom dinner parties, and the design of the show took full advantage of virtual backgrounds, sound design, and the various Zoom settings. During the devising process, we found that "Zoom jokes" like someone forgetting to unmute or someone having WiFi problems could be worked into the piece as comedic moments. It ended up that those comedic moments also helped the actors and the audience relax about technology's unpredictability. It didn't feel odd to watch the show on Zoom as it streamed live to YouTube because the virtual format felt meaningful and fulfilling. The audience didn't need to imagine how much better the show would be on stage and instead spent that energy focusing on the story and the characters.

Recently, I saw the virtual production of The Weir through the Irish Repertory Theatre. The play was directed by Ciarán O'Reilly and featured a small cast of five actors. Each actor had a camera set up and used a green screen to show the "set" of the Irish Pub behind them. It was superbly edited and pieced together. The set design was a 360-degree virtual pub background, and each actor's background would change depending on the part of the pub they were in. The innovative design succeeded in helping the audience imagine a full room in which the actors were moving and interacting with each other. I have not seen any other production be so successful at creating a united theatrical space for a group of virtually separated actors. O'Reilly's direction also smartly led the actors to use their full bodies and take advantage of different positions and props in their space.

Joe Westerfield of Newsweek wrote, Irish Rep "makes a big leap...The result is as close to theatrical experience as one can hope for these days." I certainly agree, but perhaps in that praise, also lies one of the problems with a lot of virtual theater. Maybe this is just the director in me, but when I watched the play, I had a hard time thinking about much else besides how the play would be even better if I could see these talented actors perform it on a stage with the beautiful virtual set fully realized. We all want to be keeping the theater alive, but there are also plays that will always be more successful live and on a stage. If we know that we will never be able to fully honor and "recreate" the in-person version, is it still worth trying to get "as close to the theatrical experience" as we can? Will audiences just always be left longing for more?

Another theater piece that I saw recently was a farm for meme, written by Virginia Grise, directed by Elena Araoz and produced in association with allgo, Cara Mía Theatre, and Innovations in Socially Distant Performance. It was a performance of Grise's poetic monologue about a farm in South Central Los Angeles that was built in a vacant lot after the 1992 LA rebellion. The theater piece was creative, engaging, and accessible. The layered film design and the small-scale puppetry elements of the piece would never have worked on a stage, but they worked beautifully virtually. The performance honored the virtual platform, and the use of technology and design felt intentional, while also serving the storytelling first and foremost. The piece was also short, running at only 20 minutes. I think that length is a crucial factor when it comes to successful virtual theater. Theatermakers must be aware of screen fatigue and how virtual engagement can lead to shorter attention spans. Audiences are craving theater, but it is also incredibly hard to focus on a two-act play on a screen in the same way that audiences can do so in a theater.

Instead of trying to get "as close to theatrical experience" as possible in the virtual format, maybe we, as theatermakers, should use this time to embrace art specific to the virtual world. We will probably never have a more opportune moment to make "Zoom-specific theater" or theater that so beautifully lends itself to interdisciplinary collaboration. So let's write, devise, adapt, and seize the moment's opportunity.

Some more resources:

Check out Innovations in Socially Distant Performance, a Princeton project led by Elena Araoz (the director of a farm for meme) HERE. The group has compiled incredible resources, articles, and interviews about creating art and performance during this moment.

You can read more about a farm for meme HERE and watch a recorded performance HERE.

Other incredible virtual theater works that I want to mention:

Heartbeat Opera's virtual soiree performances of Lady M (HERE)

The two Zoom-specific Apple family plays by Richard Nelson. The second, entitled And So We Come Forth: A Dinner on Zoom, can be watched HERE until August 26th. Learn more at their site HERE.

Videos