Review: EVEREST, Barbican Theatre

Joby Talbot's opera has a chillingly eerie resonance

![]()

An atmospheric story of a group of trapped explorers at the mercy of mother nature, the UK premiere of Joby Talbot’s Everest has a chillingly eerie resonance. After a week where the world has been collectively imagining the similar fate of another group of explorers, this time trapped at the bottom of the ocean rather than on the side of Mount Everest, what can Talbot’s 2015 opera tell us about hubris and humanity in the face of hardship?

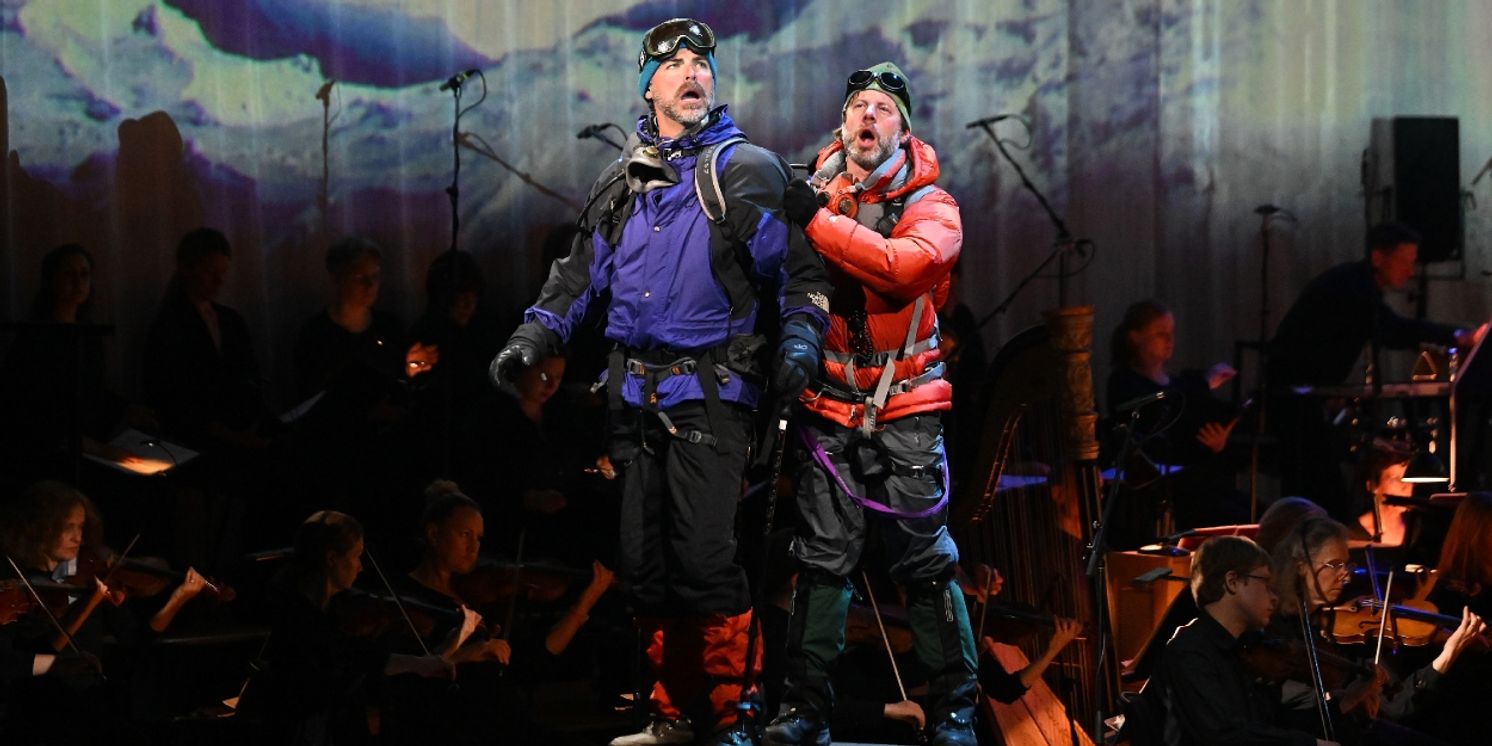

The 1996 Mount Everest disaster saw the tragic deaths of eight climbers caught in a blizzard during their descent from the summit. Talbot’s Everest is a slowly unfolding tragedy focusing on three of the climbing party. Semi-staged by director Kristen Barrett, the three men, Doug Hansen, Beck Weathers, and Rob Hall, grapple with their impending fates.

Talbot’s score drips with marauding ominousness. It is often onomatopoeic, whirring wind, icy cymbal crashes that send jittery shivers across the nervous system. Nicole Paiement masterfully conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers injecting the music with pungent sense of danger and letting it slowly undulate with terror that burrows under the skin.

From the highest mountain peak to the ticking hands of a watch, every note forebodes and marauds. Everest itself takes on a life force of their own: a recurring groan-like rumble, low warbling strings, recalls a Whale’s foreboding call. Moby Dick is a fitting literary parallel to invoke. Interestingly Gene Scheer has already penned an operatic adaption of Melville’s masterpiece with Ben Heppner.

Dreamlike visions of the three men’s spiralling minds unravel as a cornucopia of emotions. Their hope deteriorates and they are haunted by visions of love and death. Beck Weathers, performed by gorgeously smooth Daniel Okultich, is left abandoned with thoughts of his child and his wife. They appear as rose-tinted memories. An excellent Matilda McDonald plays Meg Weathers separated from her husband on the other side of the stage. She has excellent chemistry alongside Okultich, their desperate interactions are a beacon of warmth emanating in the cold.

But Scheer’s libretto tells us what Talbot’s score shows us. It maps the psychology but doesn’t generate a third dimension beyond it. It wants to juxtapose the personal stories of this particular disaster with wider questions about the nature of human endeavour and triumph over adversity, but is too clunky to breach the depth behind the latter. There are some beautiful passages, but overgenerous use of factoids and exposition saps the libretto of its lyrical force.

As a result the opera shies away from penetrating existential questions. Why? Why does anyone risk their lives to waltz with danger. Why climb a dangerous mountain (or venture to the wreckage of the Titanic in a homemade submersible)? Whilst it misses an opportunity to interogate our capacity for self-destructive ambition, it still thrills and haunts in equal measure.

Photo Credit: BBC/Mark Allan

Reader Reviews

Videos