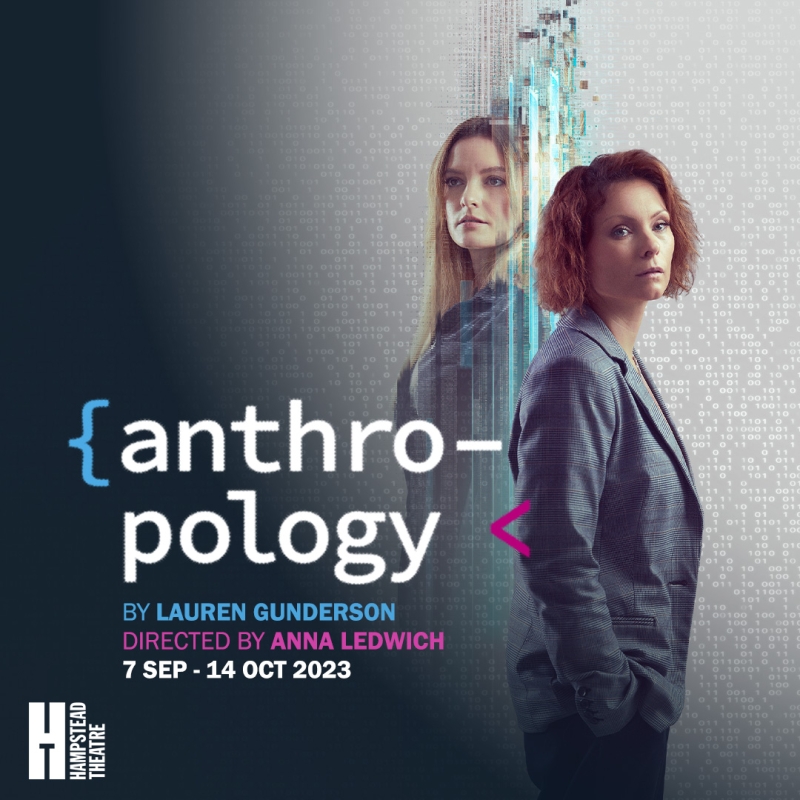

Interview: “I Love The Respect of The Practice in The UK': Writer Lauren Gunderson on Being Drawn to London and Studying AI for Her Play ANTHROPOLOGY

Lauren Gunderson asks pressing questions about AI in her new sci-fi thriller at Hampstead Theatre

In 2021 The San Francisco Chronicle published a feature story straight out of the realm of sci-fi. Joshua Barbeau, a Canadian freelance writer created an A.I.-powered chatbot to simulate his late fiancée. He would chat to the digital version of her late into the night to cope with his grief and loneliness. The programme he used, GPT-3, would enter the mainstream consciousness two years later.

Lauren Gunderson’s new play anthropology was conceived before Chat GPT brought AI-induced existential doom and gloom out of the territory of the Terminator films and into reality.

“Things happen, ideas come, you can see a revelation unfold. There is always a eureka moment. A character goes through a significant change in front of us, right? So I'm always kind of researching AI.” she says.

One day that research paid off. The article in the San Francisco Chronicle grabbed her imagination and sent it whirling with curiosity.

“This amazing story that just stuck with me. You read one of those and you can't stop thinking about it. This AI actually helped with his grief. Of course it goes wrong though. The technology was prone to these hallucinations and confabulation, which make it say terrible or strange or impossible things.”

Soon to premiere at Hampstead Theatre, anthropology imagines a similar scenario. Merril, a Silicon Valley software engineer, programmes a chatbot to simulate her late sister Angie who died in mysterious circumstances. Things take a thrilling turn when the virtual Angie starts offering information about her real counterpart’s disappearance.

Soon to premiere at Hampstead Theatre, anthropology imagines a similar scenario. Merril, a Silicon Valley software engineer, programmes a chatbot to simulate her late sister Angie who died in mysterious circumstances. Things take a thrilling turn when the virtual Angie starts offering information about her real counterpart’s disappearance.

“All plays, whatever they're about, are about humanity right? They're about people going through enormous trying things - sometimes for fun or sometimes in comedic ways and sometimes in harrowing or tragic ways. I mean, that's, that's our tool, right? Our tool is people.”

Gunderson reflected her own experience onto Barbeau’s story. What if she were in that situation?

“Then it became a thriller plot centred around a woman's grief after her sister was murdered, putting the sister into AI so she can basically say, I'm sorry I couldn't protect you. I love you. Goodbye. But then the AI wanting to help solve the mystery of her murder. They keep saying that we are in the Wild West when it comes to AI. You don't quite know what's going to happen next or what it's going to do.”

Gunderson’s play straddles the line between sci-fi and scientific fiction even as the fiction element of both seems less distant by the day. Most of the technology that is referenced in Anthropology is achievable in some form right now; a friend of Gunderson’s works as an AI conversation designer at a big tech company. She has been instrumental as a sound board for the getting the technological elements right.

“She's been my very first reader on this. She Zoomed with the cast in the first week of rehearsal and has talked to our lead Ana on several times. She’s been an endless resource to ask crazy technical questions. So is it sci-fi? Probably no. The science is pretty scientific.”

For Gunderson science makes great theatre. Her previous works have explored figures like Ada Lovelace, Charles Babbage, Marie Curie, and lesser-known ones like 19th-century astronomer Henrietta Leavitt. But this is her first play about science set in the present day.

“I think futurism is an interesting thing to play with, I just saw The Effect at the National which has, that has a feeling of futurism even though what they're talking about, clinical drug trials and the like also exists now.”

“But technology, the thesis of the play, and I think what I am coming to understand is that technology tells us a lot about us before we decide what is good for us or what it is. Technology tells us what we care about. What are we interested in? What are we scared of? Um, and technology will be there to reflect that back to us.”

For anthropology the sisterly dynamic that is reflected back at the protagonist Merril; technology becomes an extension of her personhood and grief.

“It's an extension of emotion that she can't fix by herself. It’s such a grey area.”

Reading Joshua Barbeau’s story invokes an uneasy swell of emotions. Do we feel sorry or happy for him? Pathetic delusion or a triumph over grief? The same question lies at the heart of anthropology.

“I think all responses are welcome. I think it's human, akin to drinking to forget a heartbreak or having any manner of drug or sex or any of the things that humans have at their disposal. I think that is what Merril is doing and hopefully half the audience thinks it's a terrible idea, and half the audience says, you know, if this person in my life died, I might do that.”

The conundrum throws up all kinds of moral questions.

“I think it's only interesting because it's wrong in part: if we were fully confident in her choice, it wouldn't be a very good play. In our hearts we know what Hamlet does is wrong but we keep watching because we understand this need for vengeance, this need to punish, this need to change. I don't think killing folks and acting crazy and being mean to Ophelia is a great idea. But I do understand somewhere.”

Theatre has been hesitant to explore sci-fi, maybe because film has scoped out the territory so well. The medium’s most iconic villains are monotone voiced computers or hulking androids hell bent on eviscerating humanity. Gunderson is well aware of this:

“There's always a sense, I think you put an AI into a story and it's like, oh no, something's going to go wrong. This is a thriller, there is that tension in the audience to go, oh gosh, what’s going to happen next?”

But the morality at the core of anthropology feels more personal, not just about how to process grief and deal with loss but something more fundamental to the way we communicate in the 21st century.

“Do you fly across the country to tell your dad happy 4th of July, or do you text him? You text him. Most of your friends you're watching them online. You're not going to hang out at their houses. So there is a version where you could have a fine, a fine life and be happily diluted until the day that you die.”

Photo Credit: Hampstead Theatre via Twitter/X

It’s a theatrical treat for Dakota Blue Richards who plays the AI not as a cold voiced machine but as a replica of her real counterpart. Is she playing a real person or something that looks and sounds like a real person? Gunderson giggles.

“The play asks questions. We as playwrights rarely answer them.”

But Gunderson is sceptical that AI will put her out of a job.

“My husband and I used Chat GPT to write a play in the style of Lauren Gunderson. It was only four pages long and it was terrible. I’m reminded of what this friend of mine who works in AI said to me: AI is just a tool. If you are afraid of it that is because you are afraid of who is wielding the tool, less the tool itself.”

Whilst the majority of Lauren’s work is produced in America, she is always drawn to working on this side of the pond. Gunderson’s I and You premiered at Hampstead in 2018 with Game of Thrones star Maisie Williams starring. This autumn sees the premiere of Time Traveller’s Wife play at the Apollo Theatre, for which Gunderson wrote the book for.

“I love the respect of the practice and the quality of the actors and the artists here – they have an endurance athlete quality to them. Theatre is also engrained within them. It is also part of your intellectual development, having mandatory drama classes – something that is mostly a choice in America, an extra thing that you can do rather than it being mandatory. That leads to an enriched theatre going and theatre making tradition here which America doesn't have.”

In 2021 Gunderson was queuing outside the Apollo Theatre for the first post Covid performances of Michael Longhurst’s Constellations. A stranger approached her:

“Somebody just comes up to me, obviously from work, briefcase, work shoes she was like, what's on, what's this queue for? So I said it’s this play called Constellations and I’ve heard it’s really good. And she just goes - I'll get in the queue. That’s baffling to Americans.”

It’s not just the culture that she loves, but the buildings themselves.

“Hampstead Theatre is like this. Usually the café is open all morning. You have commuters getting on the tube here and coming in. Maybe they've never seen a play here, but they have a space where they can just sit and relax. And the fact that the theatre’s open so many hours - there's a bar afterwards that's open, it's so lively and so full of humanity, and so full of culture and different people. That’s what theatre ought to be. I find that experience so radical because often in the US the theatre is just a theatre.”

London theatres also provides fertile ground for new writing.

“The stakes are a little bit different here. There are more critics and so many different kinds and flavours of theatre. It’s not doom forever if you get one bad review here. Certainly a city as diverse as London needs as much diversity on stage as on the page too. I feel this with my plays about women; some male critics don't understand all of what works about it. That isn’t to say don’t go and see plays that are not about you. Please go watch them, love them, but if you don't, don’t say it's bad because it's not for you, you know?”

anthropology plays at Hampstead Theatre from 7 September - 14 October

Main Photo Credit: The Other Richard

Comments

Videos