Guest Blog: Sacha Wares On Two New Immersive Digital Productions

The work is being shown at the BFI London Film Festival

Over my 20-year career as a director for theatre, the world we live in and how we communicate has changed beyond recognition. When I first began directing, only a tiny handful of people I knew had mobile phones; now we live a vast proportion of our lives in the digital world and our phones function as a 'place' we inhabit, communicate and connect within.

The transformation undergone by our social selves has been enormous and yet our art form - theatre - has barely changed in this time. At the start of a theatrical performance, we ask audiences to slip into their rows, face front, switch off their phones, and pretend for an hour or so that the powerfully smart device in our handbags or pockets doesn't exist.

There is a relief and a romance to this, but a few years ago - around the time Peter Brook's phone accidentally went off during a play I directed - I began to question the truthfulness of the phone turning-off moment. I started to wonder if by banishing modern technologies to our handbags, we might be failing to fully explore and express how we currently live and communicate as a society.

This unease led me to The National Theatre's Immersive Storytelling Studio (ISS), an unassuming temporary building in a small carpark, filled with cutting-edge technology and out-of-the-box thinkers.

For the last four years, with support from the ISS, English Touring Theatre, The Donmar Warehouse, the Arts Council, Creative XR, All Seeing Eye, Dimension Studio and the Genesis Foundation, I have had the pleasure of exploring a wealth of new mediums and technologies from virtual and mixed reality, to volumetric capture, testing the ability of each to tell stories that reflect the concerns of our times.

Much of the technology I have been experimenting with is in its infancy, and consequently daily failure and frustration has been very much part of the journey. But this week, as part of London Film Festival's Expanded strand, I am excited to be launching my new company Trial and Error Studio and showcasing two pieces of work that have emerged from these experiments.

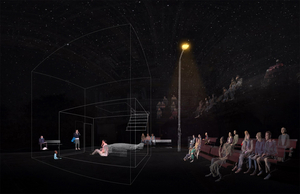

The first piece, Adult Children, is a virtual reality drama co-created by myself, Ella Hickson and ScanLAB Projects. Adult Children was written and made during the 2020-21 lockdowns and uses pointcloud scanning technology to conjure a virtual replica of The Donmar Warehouse. This digital version of the Donmar is populated by a three-dimensional cast of actors and audience who appear somehow to be gathered together, but in reality were all scanned and assembled separately during the pandemic.

Audiences experience a virtual play that never happened, a cast that never met and a social gathering that was impossible - a record of lockdown life and the feelings of dislocation that accompanied it.

The second piece, Museum of Austerity, is a promenade documentary exhibition using volumetric capture and mixed reality smartglasses. The museum is based on journalist John Pring's research into avoidable deaths of disabled benefit claimants 2010-2020, linked to changes in the benefits system.

Audiences are invited to put on the smartglasses and enter an empty space. Populating the room are eight hyperreal full size holograms representing people who died or took their own lives while struggling to navigate a hostile benefit system. As audiences walk around the space, their smartglasses track their movements, responsively triggering a soundscape that contrasts the rhetoric of British parliamentarians with personal narratives told by bereaved family members. If the audience were to remove their headsets there would be no people in the room, but with them on, they are surrounded by holographic evidence of needlessly lost lives.

I am writing this on Day 7 of the London Film Festival, my observations about how audiences are reacting to the work are ongoing and my list of things to do better next time daily growing. But three things have struck me already that give me hope for this new direction in storytelling.

The first is the pace of viewing that I have observed in audiences of Museum of Austerity. Audiences are moving much more slowly and listening much more intently and for longer than I'd predicted. They are also behaving physically in ways I had not anticipated at all. I have seen bereaved family members sit alongside a hologram of a dying figure and gently place their hands on the hand of the image, and I have learned that other audience members, new to the stories, have felt moved to do the same.

I had not imagined that holograms could elicit a physical reaction. But while the audience's physical behaviours have taken me by surprise, what has struck me most is that so far almost no one comes out of either experience mentioning the technology. They go in curious about the hardware and emerge almost universally discussing the content, not its vehicle.

It seems for most audiences, these new technologies - in spite of their novelty - very quickly become invisible and, like the lighting rig and sound speakers in traditional theatre settings, the VR headsets and mixed reality glasses just fall quietly into the background, supporting the human stories we seek to tell.

Adult Children and Museum of Austerity are showing until 17 October - find out more here

Comments

Videos