Review: THE PRISONER, National Theatre

![]() It's been a long minute - over two decades, in fact - since acclaimed director Peter Brook, who is now 93 years old and has been called "our greatest Living Theatre director", helmed a play at the National Theatre.

It's been a long minute - over two decades, in fact - since acclaimed director Peter Brook, who is now 93 years old and has been called "our greatest Living Theatre director", helmed a play at the National Theatre.

So this new production of The Prisoner, which he has co-directed with his long-time collaborator Marie-Hélène Estienne, has been long and hugely anticipated, given that it may well be the last chance ever to see a Brook production at the National.

A visitor to an unnamed land tells the story of Mavuso, who has to sit on a hill in front of a prison for two decades as punishment for killing his father, who he caught in bed with his sister Nadia. In Mavuso's mind he is there to 'repair', whatever that means.

Nobody is enforcing Mavuso's isolation and he is free to leave if he chooses - and indeed, other people such as prison guards and his sister try to make him do so. So ostensibly the main question the play asks: is it possible to be imprisoned while remaining unincarcerated?

A clear-cut intention like that is muddied by further questions that are listed in the pre-show literature. As for those who are inside (the prison), what crime have they committed? And what do they think of that man, facing them, free? Is he mad? Is he a fanatic? What sort of justice is this? Is the man looking for redemption?

We never get an approximation of answers to any of these questions, let alone to the overarching one. The Prisoner is a meditatively sombre treatise, drawing on mythological tropes to contemplate the nature of crime, punishment, redemption and society. Sadly, its failure to interrogate and elucidate its own quest hamstrings the play, making it ponderous and lacking in the dynamic propulsion that fires up the liveness of much theatre.

In latter years, Brook has aimed for a pared-down, minimalistic aesthetic to his productions, and he seems to be aiming for that quietly thoughtful, slow-Moving Theatre here. The problem is that he and his co-director seem to have decluttered so intensely that the script itself is not meaty enough to give its strong and supple cast something to really chew on.

This austerity is reflected in in the long stretches of flabby silence and in David Violi's design of 'stage elements', depicting an arid land of bleached branches and random rocks which gleam in Philippe Vialatte's jaundice-yellow lighting palette.

Many of Brook's other trademarks are present in this production too. Audiences familiar with his ambitious but ultimately flawed adaptation of the Indian epic poem the Mahabharata for both stage and television will recognise Brook's penchant for an international outlook reflected in a cast of different ethnicities and accents.

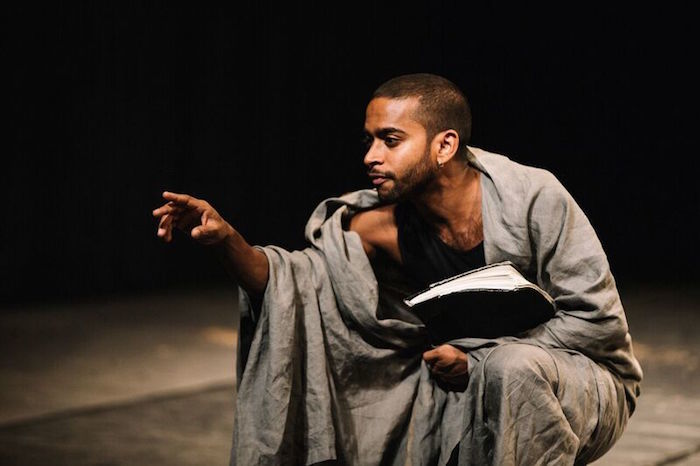

In this case, Sri Lankan Hiran Abeysekera plays Mavuso, the titular prisoner, Hervé Goffings, a French actor with Malian heritage plays his Uncle Ezekiel, Indian actress Kalieaswari Srinivasan is Mavuso's sister Nadia, and the veteran English actor Donald Sumpter, who many people will recognise from Game of Thrones, plays the visitor.

The diverse cast can't be a coincidence, as one of Brook's theatrical preoccupations is to do with the universality of archetypal narratives that make parables - and a parable is what The Prisoner ultimately aims to be. As such, it feels like a postscript to the mysticism of the Mahabharata, made all the more troubling because Nadia's sexual abuse is never addressed and so she becomes nothing more than a cipher.

At a short and swift 70-minute running time, the audience is hardly held hostage, but it's a shame that they're also thankful to escape a play that doesn't convince with its form or content.

The Prisoner at the National Theatre until 4 October

Photo credit: Ryan Buchanan

Reader Reviews

Videos