Review: CARMEN, Royal Opera House

![]() Numerous epithets will doubtless be applied to this new Carmen - whether 'controversial', 'shocking', 'brilliant' or 'novel'. But whichever is chosen to describe Barrie Kosky's concept, it will likely be obscuring the production's true stars: namely, the singers and the orchestra. Perhaps, for Kosky, that will almost be wish fulfilment, since however one labels Kosky's artistic choices, what is indisputable is how much both vocalists and instrumentalists appear sidelined in their favour.

Numerous epithets will doubtless be applied to this new Carmen - whether 'controversial', 'shocking', 'brilliant' or 'novel'. But whichever is chosen to describe Barrie Kosky's concept, it will likely be obscuring the production's true stars: namely, the singers and the orchestra. Perhaps, for Kosky, that will almost be wish fulfilment, since however one labels Kosky's artistic choices, what is indisputable is how much both vocalists and instrumentalists appear sidelined in their favour.

Finally making his debut at the Royal Opera House, young marvel of a conductor Jakub Hruša leads a Carmen that embodies the unconquerable suppleness and variation of the opera: migrating between bouts of sprightliness and eeriness, rapture and bellicosity.

Pitting high, shimmery violins against the ominous underbelly of the punctuated, plucked cellos, Hruša proportions Carmen's brazen, at times spuriously festive exterior and its menacing subtext with flawless precision - always knowing which of the two should tug more attention away from the other.

Through no fault of his own, however, there are moments when Hruša's conducting is done a disservice. This partly falls to the choice of musical material. For Kosky's original production of Carmen, staged at Frankfurt Opera in 2016, Greek conductor Constantinos Carydis compiled a version of the opera that used long-abandoned sections of Bizet's original, 1,200-page draft. Here, this production also uses that arrangement - one that lets the Habanera spill into a lengthy postlude of bustling, staccato, excessively jocose bars of song.

It's a convenient choice for Kosky's take on the opera, which includes a great deal of extras, most of them dancers - dressed in cabaret outfits, many wearing tap shoes, some sporting canes. The altered bars of the finale end the opera on a major chord, facilitating Kosky's need to have the stabbed Carmen rising from the dead.

While the addition of lost music is a highly debatable subject in the opera domain, here the supplementary pages only manage to impoverish an opera that's been doing pretty well for nearly one and a half centuries.

Much of Hruša's conducting - as well as the performers' singing - is drowned out by dancers' tapping feet. This does not apply to Carmen's "Séguidille", her dance for Escamillo; that section excludes a dance. Instead, all kinds of different dancing happens quite sporadically throughout the whole production.

Because a large amount of it is done with tap shoes and deliberate finger clicking, the noise stampedes over the orchestra and sometimes even soloists. The dancing - magnificently executed by professionals - also incoherently hops genres: at one point evoking Nineties disco favourite the Macarena, at another window-washing like an Eighties music video.

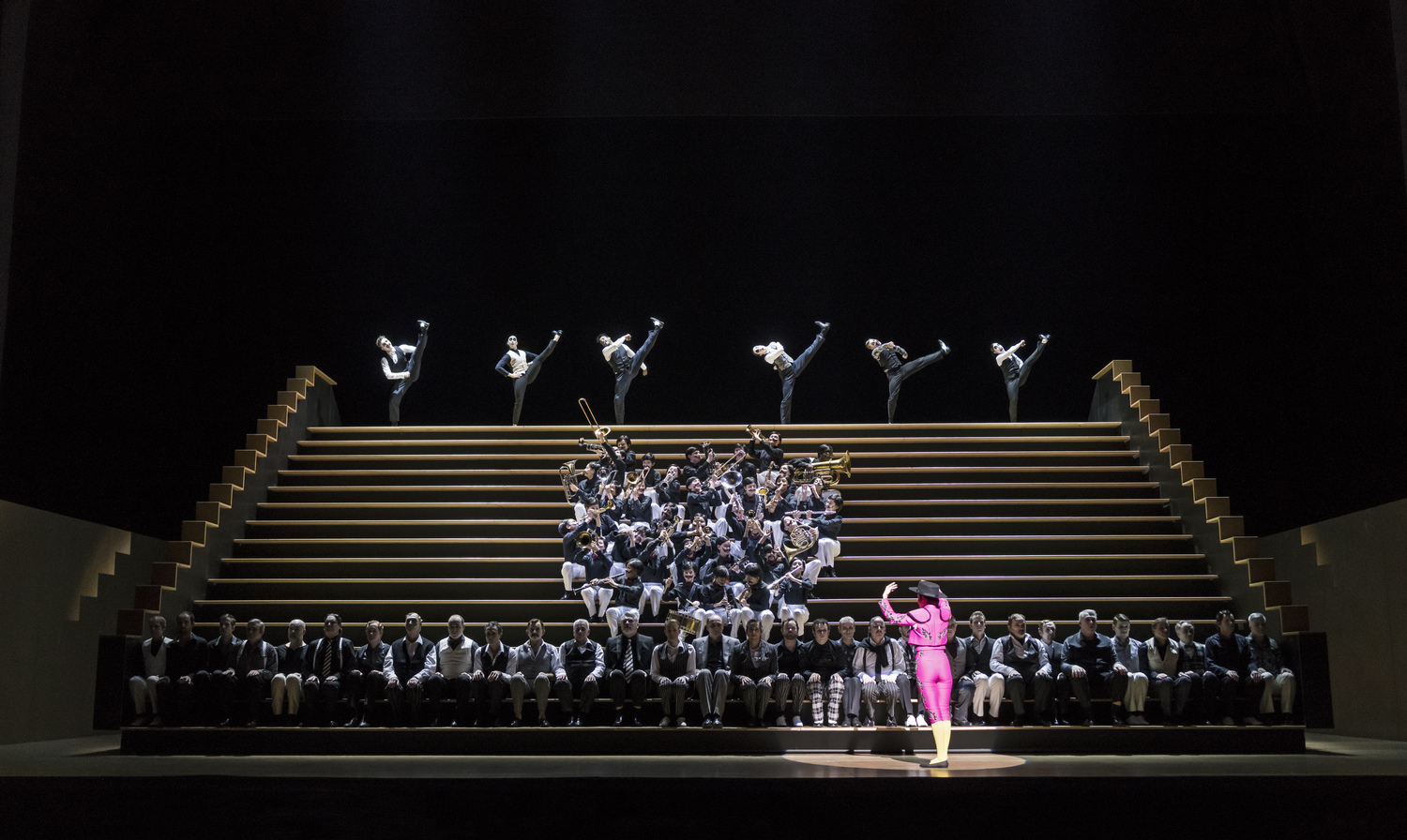

The majority of the production takes place on a colossal, 16-step staircase that occupies most of the stage. This means that often soloists and chorus singers have to perform as they run down these hazardous steps.

Given the physics of the backdrop - a dented surface that contains narrow steps - vocal projection is destined to disperse in several different directions, never reaching its target. That doesn't happen, and with an inauthentic veneer about all the singing, it suggests that microphones are possibly used overhead.

Considering these exceptional circumstances, the singers apply an Olympian effort. As Carmen, Anna Goryachova must perform the Habanera in a full gorilla suit. Thankfully, she is allowed to take her mask off when the vocal line appears.

The lower register is of a black, seductive hue and Goryachova navigates her voice to express as much of Carmen's alluring entrapment as possible; the "tra-la-la"s that prelude her "Près des remparts de Séville" are projected with the audacious mezzo of an unfailing, all-knowing cunning. While many of her higher notes are on shaky ground, her trills are largely clean and always carry vigour.

What is disappointing nonetheless is how Kosky's directorial demands inhibit her. Defending herself before Don José at the start of their "C'est toi, c'est moi" duet, Carmen is subjected to standing at the bottom of the large staircase, her black trailing dress sprawled out in an upside-down triangle over the steps. It's all very pretty - but the singer cannot move, cannot express herself in this upending scene.

Much of the same can be said for the others - who are forced often to stand still in groups, or else to move in highly particular, ill-choreographed ways - rather than yield to their natural responses as artists.

But the greatest error this production makes is the replacement of Carmen's dialogues - the very exchanges that make it an 'opéra comique' - with pre-recorded audio of text collated from Mérimée, Halévy and Meilhac. The voiceover not only compels all the performers to be still, it sounds as lifeless and computer-generated as an automated message on the end of a customer service hotline.

Francesco Meli's Don José sadly succumbs to a great deal of vocal instability. At times out of sync with lover Micaëla in the "Parlez-moi de ma mère" duet, he cracks on the first note of "La fleur que tu m'avais jetée" and, in spite of an accurate, bombastic attitude of aggressive possessiveness, occasionally yields to out-of-tune notes and short phrases.

In an unusual turn of events, Kristina Mkhitaryan as the customarily forgotten Micaëla makes the most lasting vocal impression. Her high-noted trills dazzle and ring with a clean, silvery texture; they dissolve into diminuendo like the hushing vibration of a spoon after hitting the surface.

His voice largely obscured by the director's choice to have the chorus laughing and squealing hysterically during the Toreador song, Kostas Smoriginas' Escamillo exudes physical effrontery but a crunchy, unusually tremulous baritone voice. While he fights against distracting onstage antics with much gusto, the voice at times succumbs to some haphazard cracks.

Kosky's production is a clutter of disparate elements. While there is nothing wrong with attempting a monochromatic Carmen, too many directorial ideas prompt the audience to lose focus. The dim lighting and spotlights, the dancers' occasional jazz hands, the bowler hats and canes - all give a 'cabaret' feel.

Carmen could in fact take place in a cabaret, but not one where Carmen is dressed as a ringmaster one moment and a gorilla the next. Nor is this the triumphant emergence of a vaudevillian operatic genre; vaudeville is not usually sold at such high ticket prices, and if it is, that includes Champagne and a seat at a table.

Carmen is at the Royal Opera House until 16 March

Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Reader Reviews

Videos