Interview: Medical Ethicist Dr Daniel Sokol Talks THE DOCTOR

Renowned medical ethicist Dr Daniel Sokol was the bioethics consultant for Robert Icke's acclaimed new play The Doctor, now playing at the Almeida Theatre and starring Juliet Stevenson. He talks to us about his role and the fascinating area of medical ethics.

What is bioethics?

In short, it's the study of the ethical issues in the biological sciences, medicine, and healthcare.

What do you do?

As a medical ethicist, I advise clinicians, patients, relatives, research institutions, and even Government departments about ethical issues, as well as writing books and articles, giving lectures and training doctors.

I also practise as a barrister specialising in clinical negligence. I advise people and institutions such as NHS trusts and private clinics about legal matters relating to medical treatment. If the matter goes to trial, I represent them in court.

Can you give us concrete examples?

Last week, I advised a GP who struggled to deal with a severely ill patient who lived at home in squalid conditions and refused to go to hospital. I also advised relatives of a patient who were fighting the hospital's decision to stop aggressive treatment for their elderly father.

I have advised the Ministry of Defence on the ethics of military research. Still within the MoD, I've taught military doctors how to resolve their ethical dilemmas on active duty in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

As a barrister, I represent patients and more rarely the NHS when things have gone wrong in hospital or in a GP surgery, such as a missed diagnosis of cancer or a botched operation that leaves the patient significantly worse off than they would have otherwise been.

As a barrister, I represent patients and more rarely the NHS when things have gone wrong in hospital or in a GP surgery, such as a missed diagnosis of cancer or a botched operation that leaves the patient significantly worse off than they would have otherwise been.

Interestingly, I have a case at the moment involving a client who, as a young boy, was not told by the doctors that he had a life-changing diagnosis. There are echoes of The Doctor in that case.

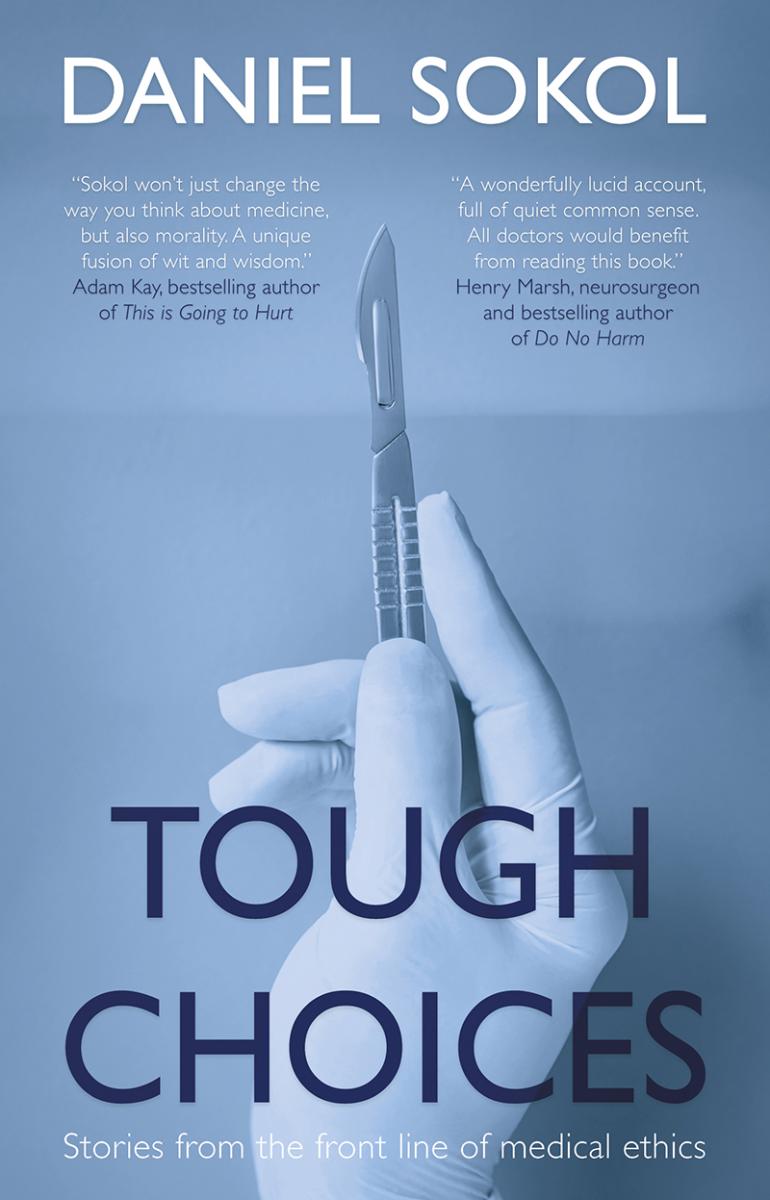

Some of my most interesting cases appear in my new book Tough Choices: Stories from the Front Line of Medical Ethics.

Is The Doctor quite realistic in the way it depicts the ethical scenario involving the priest?

I have not come across a similar situation in my own practice, but I have had cases where the patient would not listen to anyone from the clinical team, and we explored the possibility of asking a priest or other religious authority to talk to the patient. Priests, imams, rabbis and other religious figures can sometimes be of great benefit to patients in hospitals.

The central scenario in the play is likely to be rare in reality, but when I read the script (although not the final version) I felt it was realistic and believable. Thankfully, so far the reviews have been stellar and no one has criticised the medical ethics!

The play looks at how public opinion, PR and social media shape a lot of these debates. Is that a problem now?

It is highly topical in light of recent cases such as Charlie Gard and Alfie Evans. These cases revealed the distorting effects of social media and the harm that can ensue to many of the parties involved - from the medical experts, to the healthcare staff, to the patient himself.

How were you approached by Robert Icke?

Robert contacted me in March, asking to meet me to talk about the ethics and law of a new play. Intrigued, I met him in my Chambers later that month.

I'm not sure if he knew then that I had written my PhD on the ethics of truth-telling in medicine or, more simply, on whether doctors should always tell patients the truth. This question lies at the core of The Doctor.

I gave him a copy of the PhD (instantly doubling my readership) and Tough Choices, and we kept in contact thereafter. I also read a version of the manuscript and provided detailed feedback from a bioethical perspective.

What did he want to know in terms of specific medical procedures or ethical debates?

I felt he wanted to know as much as he could about the ethics of the play's central scenario and other truth-telling debates in medicine. Why should doctors tell the truth to patients? What ethical principles are in play? Are there any exceptions and, if so, what are the moral justifications for those?

In what way was this consultancy different from your usual work?

No one will come to great harm if I make a mistake and I'm less likely to be sued! Unlike most of my work, which involves large doses of human misery, pain, distress, and the stress of litigation, this was fun. It felt more like an academic exercise, in which I was trying to identify and expose the richness and complexities of the ethical issues in the play's scenario. It also gave me an insight into the mind of a great theatre director.

Finally, is medical ethics an issue that the public should be grappling with more?

Absolutely, especially as medicine becomes increasingly capable of keeping us alive in states that many of us would consider so grim that death would be preferable. At the end of life particularly, ethical questions may arise in relation to our own care or those of friends and relatives. Setting out on paper our thoughts and wishes about what makes life worth living for us can be helpful to decision-makers. This document is called an 'Advance Statement' and you can read more about it here.

And there is also the related issue of doctor-assisted suicide, now legal in many jurisdictions, which may affect us all. Should this be legalised in this country?

That is a dramatic example, of course, and medical ethics captures a very broad range of issues, from the involvement of doctors in cosmetic genital surgery to what drugs or treatments should receive NHS funding. Hopefully, The Doctor will generate interest in this fascinating and important discipline.

Tough Choices: Stories from the Front Line of Medical Ethics is available on Amazon and all good bookshops, RRP £9.99.

The Doctor continues at the Almeida Theatre until 28 September - read our review here

Photo credit: Manuel Harlan

Comments

Videos