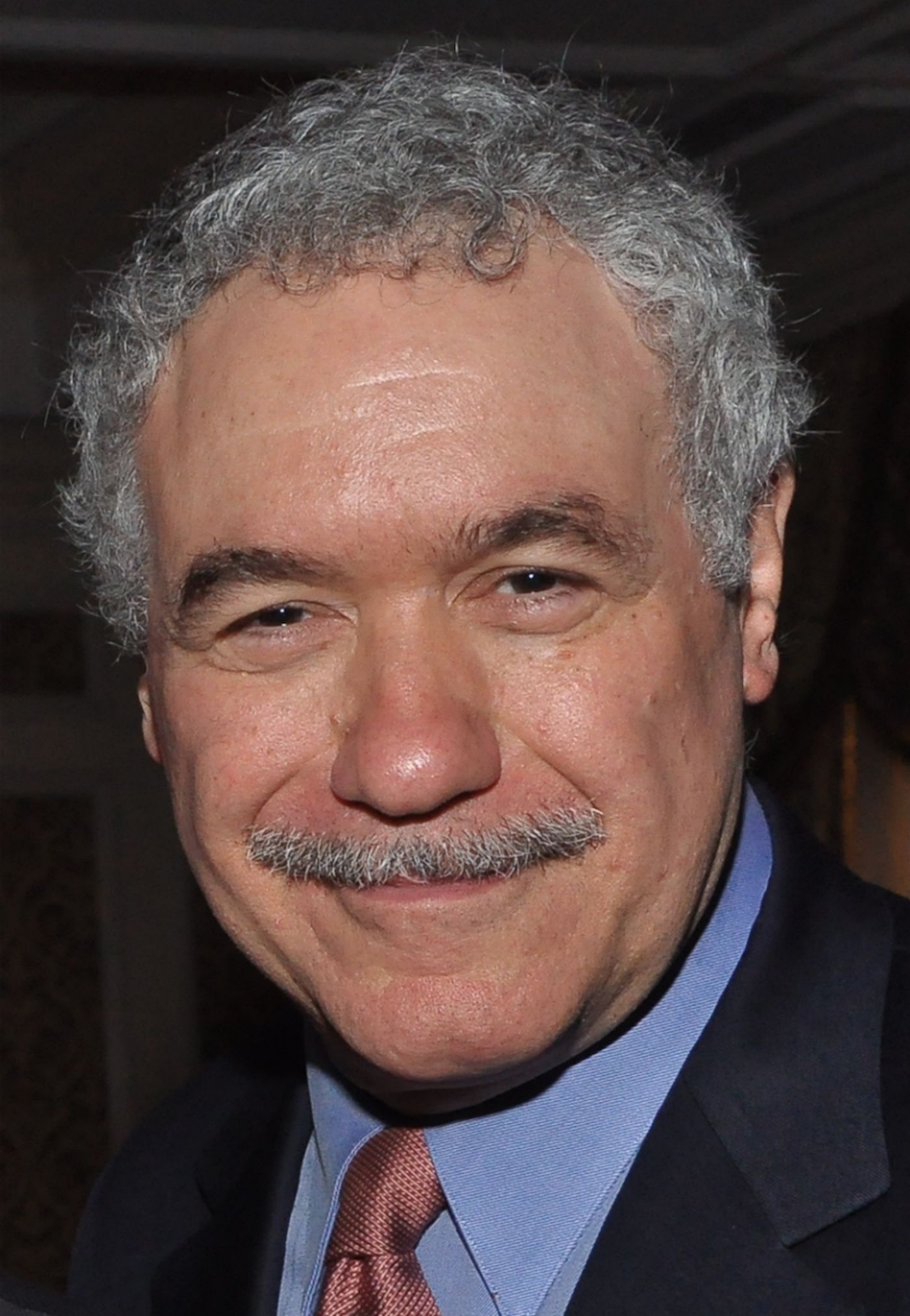

Interview: Larry Blank On Being Music Director of the Olivier Awards

Larry Blank is a prolific composer, conductor and orchestrator. He's worked on shows on Broadway and across the States, including Sugar Babies, Phantom of the Opera, A Chorus Line and A Little Night Music, as well as contributing to orchestrations on films like The Producers and Chicago.

Blank is a regular conductor for BBC Radio 2's Friday Night is Music Night and is the music director and orchestrator, along with Mark Cumberland, for the Olivier Awards.

How did you first become interested in music?

I'm a native New Yorker and I went to the High School of Performing Arts as a drama student. I grew up going to the New York theatre since I was a little kid. I had always taken piano lessons and guitar lessons at my mother's insistence, so I was adept at playing the piano and I liked show music. When I was in school and my interest in musical theatre was growing, I decided I'd rather be a musician than an actor.

I was getting hired to do Off-Broadway shows and Off-Off-Broadway as a rehearsal pianist because I was probably the least expensive pianist in all of New York City. My reputation got around and I started doing a lot of work around New York on musicals.

Actually, in 1968 I was in high school and I received a phone call from a local piano player in town named Barry. Barry said to me, "I got your name from some other people and I'm working on an act called Adam and Ira", who were two comics. He needed to be replaced because he got a job working with some singer named Bette.

Of course, that was Barry Manilow and the singer was Bette Midler. So he went off with Bette Midler and I was doing Adam and Ira. And that's how my career got started.

What was your first professional job?

I started working as a rehearsal pianist and there were a lot of little Off-Broadway shows that didn't go very far. I ended up doing some shows at Equity Library Theatre, which was run by Actors Equity and it was kind of a big deal at the time. Nobody got paid, except me as the staff pianist when I was like 17 or 18 years old. I started doing some musicals there and I decided it was also a good idea to study music.

I started taking lessons privately from various musical directors I met around town. I would take theory lessons and composition. One of them was a pianist and opera coach named Lesley Harnley. Another guy who took me under his wing was Rudi Bennett, who was the assistant conductor and conductor on many musicals, most notably conducted most of the run of Man of La Mancha.

I met Don Pippin, who was one of the last music directors to win a Tony Award for music direction. He is still a close friend and mentor now that he's in his nineties. He was the original conductor of Mame, Chorus Line, La Cage aux Folles, and many other shows. He was a rather big force and he was the one who actually promoted my career as I studied.

When I decided to become an orchestrator, I was mentored by Irwin Kostal, who was the orchestrator of West Side Story, Mary Poppins and Sound of Music. He met me when I was conducting a Broadway show called Copperfield in 1981. He said, "Why don't you come to California and I'll teach you to write your own music?".

And that's what I did: I moved to California in 1982 or 1983 to be the music director of the tour of Sugar Babies.

What have been some personal highlights of your career?

In 1975, I was asked to take over the Broadway musical Goodtime Charlie with Joel Grey and Ann Reinking. What was most interesting about it is I was 22 years old. I was successful at it and Joel Grey made me music director for his act.

Don Pippin recommended me to Michael Bennett and I was hired as music director for the international touring company of A Chorus Line in 1977. I was 25 years old. Michael Bennett was a very powerful man at the time and A Chorus Line was a gigantic show. The international touring company was actually the company that opened in London at Drury Lane in 1976 with an American cast. When it came back to America, I was hired as the music director. I conducted it for a year.

Marvin Hamlish, also through Don Pippin, took a liking to me and hired me as the music director on Broadway for They're Playing Our Song. After that, the rest is history. It established me as one of the Broadway conductors even though it was my third show on Broadway. But it was my first show from the beginning on an original musical.

I did a bunch of shows after that and worked my way out to California. I had more interest in writing for television and film, but my conducting skills got me a lot of jobs.

Is working in film and television different from working in theatre for a live audience?

The difference working for film and television is you spend a lot of time alone. Basically you're sitting in a room writing all the time. The only contact you have with reality is when you face the orchestra in a recording studio and you do it for a few days, as opposed to the theatre where you show up eight times a week and have an audience behind your back, responding instantly. The energy of live theatre is really special.

You've conducted in both New York and London and across the world. Do you find audiences react differently?

Audiences react differently in different places because of different cultures. I did find what's good is good everywhere. But what's bad is not necessarily bad everywhere because of different tastes and cultures. I don't mean that as a criticism, just a fact.

With the really good things, people respond viscerally no matter where they're from - whether it be Europe, Asia or the United States. People react to the emotion behind the music, especially in theatre.

You're the music director and orchestrator for the Olivier Awards along with Mark Cumberland. When did you first become involved with them?

The Olivier Awards had of course been around for quite a while, but it was more or less an intimate event in a ballroom. The Tony Awards were the same way when they started out, just a party in a hotel ballroom. Somewhere in the 1960s in the States, it started to be broadcast, though it was still a nothing event.

The Oliviers was basically the UK version of the Tony Awards to honour excellence and for everyone to honour their own. A few years ago, they decided to go more mainstream with the Oliviers, and the producer for Society of London Theatre and the Olivier Awards is Julian Bird. I had been recommended to Julian by various people, mostly notably theatre producer Kim Poster, who is an American producer in London.

They basically wanted someone who knew musical theatre and had worked in the UK as well as the States, and it seemed to be me. David Charles Abell was hired as the music director and I was hired kind of as a consultant to give the feel of an American awards show in terms of the music. They were trying to maintain its integrity as British theatre, but show business was what they were trying to put to it. I've been with it ever since.

Any Oliviers highlights over the years?

They've all been pretty exciting, and for me to be in the building or on the stage conducting with people like Angela Lansbury, Stephen Sondheim, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Cameron Mackintosh, Dame Judi Dench, all those kind of people... It's quite an honour to be a part of that, since I'm a Yank.

What are some of the challenges?

With the Oliviers, it's not just having the knowledge of the West End and Broadway and all the different composers. It's having knowledge of television production. Being the music director of the show is also being the musical director for the television broadcast or radio broadcast, which has other requirements. And of course I had that experience.

It's also about accommodating all of the various productions without damaging their content. We're on a big stage with a big orchestra and some of the shows are naturally more intimate in their original surroundings. It's the desire not to ruin them in the process, and we try very hard to honour that.

Sometimes, when there's a revival of a show that originally was in a much bigger venue - for example Sweet Charity on Broadway was a giant production with 26 musicians, and they were doing it at the Haymarket here with maybe 12 people in the orchestra - I didn't want to destroy that intimacy, but when we could restore it to the full size, we would try to do that.

What are you looking forward to this year?

I love playing the Royal Albert Hall because it has so much history and it's just a giant honour to be in the building at all and in London.

And I get to work with the BBC concert orchestra, which is a wonderful orchestra. I've worked with them a lot over the past few years; I do Friday Night is Music Night very frequently with producer Anthony Cherry. So I'm well known to a lot of the local performers. It's just a thrill to still be working with a big orchestra and having a big audience there to enjoy it.

You're also doing the Friday Night is Music Night with Jason Robert Brown and the Alan Jay Lerner Tribute at Festival Hall later this year. Are you excited for those?

I'm very excited about doing the Jason Robert Brown show, because he and I have been friends for a long time. I'm one of the orchestrators on Honeymoon in Las Vegas, as well as Prince of Broadway, and I've done other projects with him. I get to work with the BBC concert orchestra, my producer friend Anthony Cherry, and Jason!

On the Alan Jay Lerner show, I get to work with producer Julian Bird from the Oliviers. I'm actually old enough to say that I knew Alan Jay Lerner. He was on a couple of the shows I worked on as an advisor. Growing up in New York I was very familiar with Lerner and Loewe, and I saw a lot of the shows originally as a kid. And also it's great to work with the BBC concert orchestra again.

What's next? Is there anything else you'd like to work on?

I'm working on a recording with a singer named Christine Andreas, who was Eliza Doolittle in the 1976 Broadway My Fair Lady revival. She was also Laurie in Oklahoma in 1979 and in a lot of other Broadway shows. She's going to record a CD of Edith Piaf songs that I'm going to orchestrate and conduct. She's also going to be in the Lerner show.

I work regularly with Michael Feinstein. I'm the resident Pops conductor with the Pasadena Symphony. Michael is the Pops conductor, which means when he sings, I conduct. I have a whole bunch of concerts during the summer in Pasadena, which is near my home in Los Angeles.

I'm also doing more work in Paris. The culture is very different in Paris, but they're starting to appreciate more musicals. They're trying to create their own. Of course, what more naturally would they follow except American and British musicals.

I'm also working with composer Richard Kagan on a new musical called Hanava Music Hall premiere in Coral Gables, Florida this fall.

Is there anyone whose work you admire right now?

I'm a big fan of Jason's, which is a good thing. I also orchestrated A Christmas Story on Broadway for Pasek and Paul. I admire their work, and I like Lin-Manuel Miranda, whom I don't know but is of course a major talent. I'm looking to see where Broadway goes next.

Any advice for aspiring music directors or orchestrators?

They should listen to everything - all types of music. Be prepared, do their studying, so that when the job comes, they are ready. These days, there's no room for on-the-job training. There isn't as much product in the way there was. There used to be a lot more musicals happening, and as one brain surgeon said to the other, "This isn't serious like show business". It's all gig money-related now, so people have to be at the top of their form.

The other thing is they should try to align themselves with existing music directors and orchestrators. I'm always very responsive when people write me. I invite them to rehearsals, to observe and pass on my knowledge as it was passed on to me. People were very generous with me. You really need to have mentors and to have people to guide you and show you how to do it. It's not just learning about how to read music.

The Olivier Awards take place on 8 April at the Royal Albert Hall

Videos