Interview: Designer Dick Bird Talks NIXON IN CHINA

During the shutdown, we're taking the opportunity to look back at some memorable productions. Here, Dick Bird discusses his career with BroadwayWorld, and gives us some fantastic insights into designing the Royal Danish Theatre, Teatro Real Madrid and Scottish Opera's co-production of a modern classic: John Adams' Nixon in China.

What was the first production you saw that inspired you?

I wish I could say it was something more esoteric, but it was probably an all-boys prep school production of Arsenic and Old Lace performed in the school's entrance hall. I was only seven at the time, but I was gripped by the idea that this mundane daily space could be transformed into a living room that we believed had a cellar, with an old man digging the Panama Canal in it. The old man would have been 13 at the most.

Can you tell us a bit about your route into the arts?

I was very involved in drama at school. I was also quite good at art, which the school saw as something I should get over as quickly as possible, so I could concentrate on more useful subjects, like geography.

So I had my last art class at 13, which may have had a lot to do with my not becoming a designer until I was 35. I studied theatre at university, specialising in directing. Then, very influenced by Bertolt Brecht, I formed a rather unconventional non-theatre theatre company in south London, with the express intention of changing the world.

As that didn't happen, in my late twenties I took a postgraduate in Directing at Goldsmiths, and in study periods in Amsterdam and Berlin discovered the works of the Polish directors Tadeusz Kantor and Josef Szana, who have continued to influence me. As my ideas around theatre became more object-based and less marketable; I kept myself alive with carpentry, making kitchens, wardrobes and beach huts for commission. This led to building small theatre sets and then some construction work for TV, at which point I took on a workshop, also making models and props for television designers.

Eventually, one of the theatre companies I was building for lost their designer, and I was a cheap choice to design and build their next show. It was a revelation. As a builder, after an all-nighter fitting up in a studio theatre, I had always felt a sadness packing up my tools just as the director and cast arrived to start technical rehearsals. As a designer, I sat in the audience on the first night with an absolute sense of having arrived home. As mentioned before, I was 35.

What was this first design job like?

It was Vagabondage at London's Young Vic, with the wonderful experimental visual theatre company Primitive Science. I worked with the water artist Mario Borza to make a cage of water over a long reflective pool, at the end of which stood a huge old door with barred windows and a Hand of Fatima door knocker. In the darkness, little steam boats emerged from secret water gates onto the pool, and actors tumbled impossibly out of tiny suitcases.

Talk us through your design process: what's the starting point? How much does it change as you're developing a production? Are you mainly working on your own, or with a team?

I try not to overthink a production before meeting with the director. There's a danger in getting too attached to an apparently wonderful idea that doesn't chime with the director at all, and then having to mentally back pedal. I'll read a text or listen to an opera as much as possible, making detailed but general notes and looking at the writer/composer's biography and performance history. Endless browsing through images. Thinking about the relationship of this particular production to its particular projected audience.

A direction of travel can be agreed with a director either very quickly or very slowly, and a design can develop in a very smooth linear fashion, or as the result of multiple rejected propositions.

I do a lot of my work and make many of my discoveries in the model box. Over years, I've developed ways of drawing on a computer, printing and cutting out, which allows me to build, throw away and refine models quite quickly. It's almost always in white card to begin with, allowing the effect of mass in space to be explored without distractions of detail and colour.

I get so involved in model making that sometimes I have to create a disruption, by taking myself out to a restaurant with my notebook. I find that a good meal with wine is the best condition in which to let ideas run freely - and generally the better the meal, the better the ideas.

I don't usually work with an assistant until quite late in the model making process, as I slightly resent the fun they are so obviously having cutting out endless repetitive forms, while I am drawing up and solving logistical problems. I have some wonderful assistants.

Once the design is delivered and approved, I then get to work with extraordinary technical teams, set builders, scenic artists, costume and prop makers... The relationships with these craftspeople can have a huge effect on shaping the finished work.

What are some of the most challenging productions you've worked on, and the most satisfying?

A production of Tejas Verdes by Fermín Cabal at the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill with the director Thea Sharrock in 2005. It's a searing piece: six monologues by women about the Chilean Disappeared under Pinochet. It seemed a very important piece to make, but the testimonies were so unremittingly dark. The question was how to put the monologues in front of audience members who had come from work or home or the pub, without switching them off, haranguing or alienating them.

In the end, we filled this tiny space above a pub with real pine trunks "rooted" in real earth, and disappearing up into Mark Jonathan's extraordinarily beautiful and invisible lights. The audience walked in through a corridor of filing cabinets stuffed and overflowing with the files of political dissidents. Turning a corner led to a wall of burial niches, one of the grave tablets missing and through which you could look down into what seemed a dark forest with people assembling.

The actors emerged from the darkness among the audience as we stood in this dark clearing. The space had the quality of a fairy tale, a place where people would gather to tell and listen to stories. It was incredibly powerful.

%2C%20Nicholas%20Lester%20(Chou%20En-lai)_%20Scottish%20Opera%202020_%20Credit%20James%20Glossop_.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

So, Nixon in China: did you know the work beforehand?

I did. I worked with Penny Woolcock on Les Pêcheurs de Perles at English National Opera and the Met. She is an Adams aficionado, having made an excellent film of The Death of Klinghoffer, and the ENO/Met's production of Dr Atomic. I've been a fan of Peter Sellars' work since the days when I thought I was a director. I've had the CD of Nixon for about ten years, waiting... The music is quite fabulous.

What were you and director John Fulljames most excited about when you embarked on the process?

I was most excited about making a big aeroplane arrive in Act I, Scene I. In our first phone conversation, John said "We don't really want a big aeroplane, do we?". I agreed that we didn't.

Where/when did you decide to set the production? And is that kind of decision different when the piece is based on real events?

John's starting point was that the events and characters of 1972 were no longer fresh in people's memories as they would have been for the original audience in 1987. So, we couldn't rely on our contemporary audience having the historical knowledge or even the preconceptions that went with the first production.

We wanted to find a framing device that would place us firmly in our present, and allow the events of 1972 to be examined and elucidated within their historical context. We went through worryingly many ideas over the first six months as the design deadlines approached.

I always find the edges between reality and artifice in the theatre very interesting. The proscenium is one such boundary that we don't always think enough about, and of course there are edges within edges. We put a hyper-realistic recreation of Mao's office in a crate in the model box at a very early stage in the design process, as a way of containing the past. Mao's embalmed body, like Snow White in a glass case, was another such contained moment, and the idea of an archive, a sort of historical repository full of boxes containing other artefacts and pasts slowly emerged.

It was quite coincidental, as far as these things ever are, that Donald Trump was making Nixon-like overtures to Kim Jong-un at the time we were thinking about all this, and the idea of a sort of government archive in which researchers would sift through history for clues to the present began to settle.

%20Mark%20Le%20Brocq%20(Mao%20Tse-tung)%2C%20Eric%20Greene%20(Nixon)%2C%20David%20Stout%20(Henry%20Kissinger)%20Scottish%20Opera%202020_%20Credit%20James%20Glossop_.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

I love the concept of inviting us into the archives - the making of the myth of Mao. Can you talk us through how you created that framing, and what materials you used?

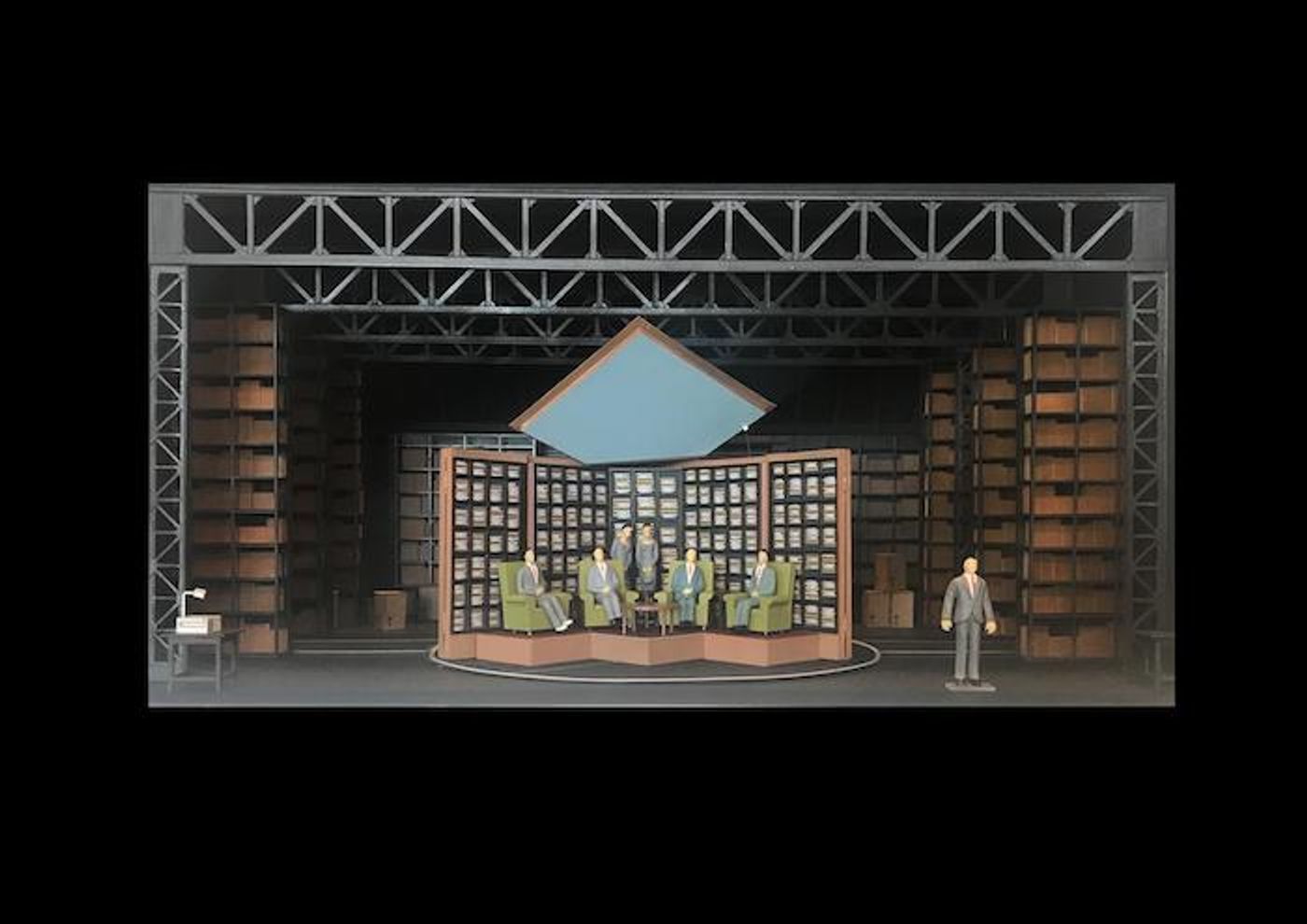

We wanted the archive to seem endless, as if this was just a small corner of a warehouse that contained evidence of all of political history. The frame of the set was metal sliding shelving units, each six metres high, that tracked in pairs below girders, allowing us to create a constantly changing space. Each shelving unit was filled with cardboard boxes from which objects could be produced, and which together acted as large kinetic projection surfaces.

From upstage, other tracks ran down onto a central seven-metre diameter revolve, which was essential to the delivery of many of the scenes.

The contents of the archive were the result of meticulous research and fabrication, much of it by the Props Department at the Royal Danish Opera in Copenhagen. I also had the good fortune to land a job working in China early in our preparations for the show. On my days off, I could trawl through flea markets in Beijing and Xi'an, where I found extraordinary materials from the Cultural Revolution, including a 700-page manual for the ballet The Red Detachment of Women, which forms the centre of Act II, Scene II of Nixon in China. This book contains the music, 300 pages of notated dance steps, all the sets and props with precise dimensions, the costumes, even the lighting plot.

How did you want to incorporate projections into the design?

We were given access to the Richard Nixon Memorial Library's archive, which contained large quantities of Super 8 film of the visit, shot by the participants at the time, and we knew from the beginning that projected footage would be a large part of providing historical context. Working with video designer Will Duke, we invented novel ideas and surfaces for the delivery of the content. An onstage camera with a live feed allowed the "archivists" to place objects under the lens, and for the audience to see them magnified

Were you pleased with the end result? And with how audiences responded to it?

We were very pleased with the end result in Copenhagen last May, and the chance to rework it as a revival at Scottish Opera has been incredible. It was a chance for another four weeks to explore it with a different cast of singers, all of us finding new depths in the music, in Alice Goodman's libretto and in the production. It's been amazing. The thought that we will be working on it again in Madrid in the future is very exciting. The audiences have responded with great enthusiasm, to the music and the ideas.

Any details in particular that you're proud of?

Well, in the end I was very proud of the arrival of the aeroplane in Act I, Scene I. In the Sixties, my grandfather had a Super 8 camera, and at family gatherings we would get out the clattering projector and the rickety collapsible projection screen and watch his home movies. A few minutes of intense saturated colour punctuated by what seemed hours of locating spools and threading sprockets. I used to like to watch from behind the screen, where everything was in reverse and you could watch the projector too.

For our aeroplane arrival in Nixon in China, which is a massive musical moment, we had the chorus, as archivists, set up eight Super 8 projectors in the centre of the revolve and eight portable projections screens on its edge. As the real footage of Nixon's plane flickered out of the projectors onto the screens, the revolve began to turn, creating a sort of massive zoetrope of the Beijing landing. It was tremendous.

What I love about working with John is that, not only did he think this was a good idea, but that as a director he had the confidence and patience to negotiate an opera chorus through the exact placement of these machines and screens with all of their cables and wiring, while singing extremely difficult music, and the calm perseverance to make it happen.

How are you coping during the shutdown? Do you still have design projects on the go, and if not, do you pivot to other work?

This could be a whole article! Like everyone else, my normal working life stopped from one day to the next. I was packing to board a plane for Sarasota Ballet when the borders and theatres started closing, and within three days, my next six months' work was in suspension.

Having spent 20 years racing from one production to the next, it has felt extraordinary to have the brakes jammed on so hard and so suddenly. I'm still working remotely with the team at the Greek National Opera on the technical phases, prior to the build of a Don Giovanni which should open in December. I also have projects to work on for next year - an opera in Australia, ballets in South Africa and Japan - although as things stand, that seems rather far away. Clearly we have some difficult times ahead, and it's hard to know how the world will have changed by then.

In the meantime, I'm very lucky. I have 20 years' worth of jobs to do around the house, and a garden I love that is too often neglected, and will probably become an earthly paradise if this goes on for as long as it seems it might.

Find out more about Dick Bird's work here and Scottish Opera here

Photo credit: James Glossop

Videos