Review: AMERICAN PSYCHO at Monumental Theatre Company

The production runs through July 21st

If your initial reaction to hearing there's an American Psycho musical is "what, really?" You may not be alone. Many uninitiated aren't aware of the musical adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis's 1991 novel. You might have the same reaction when hearing a production of the show is being performed in the black box theatre of an Episcopal high school. Regardless of your reaction, that might be where you find yourself as a DMV theatergoer, as Monumental Theatre Company's latest production is that.

For those unfamiliar the show follows Patrick Bateman, a young investment banker living high on the hog in New York City. Patrick is different than all the men around him, who would appear, on the surface, incredibly similar. He's a music buff, a news junkie, he knows all fashion faux pas and would never make them. Oh, and he is also a psychopath.

Throughout the show, audiences are invited into the violent internal life of Patrick, and forced to become accomplices in his increasingly violent acts. It's not just the violence that we are on the ride for, it's Patrick's ever-decaying psyche. The show takes place in the 80s, and as Patrick dissociates from reality, any form of identity or memory he once had, so does "modern" America around him: something far and foreign from any sort of image or values it ever claimed to hold. America decays around the psycho into shiny, consumable parts, and Patrick is lost in them.

There are two types of tickets available for the show, the "Psycho Experience," and "Riser Seating." Riser seating is, as its name would suggest, typical theater seating on risers, whereas the "Psycho Experience" involves another level of immersion. The set, designed by Michael Windsor and Laura Valenti, while mutable and functioning as many locales, is grounded in the concept of a nightclub. A bar (which functions as a real bar and a set piece), an elevated platform, and long benches and bar tables on which "Psycho Experience" audience members sat. The club seating created a mini arena theater within a theater, so to speak, which was integrated into the show in novel and clever ways. Info cards on the tables let theatergoers know that the benches lift up for storage of personal items, and at various points throughout the show, Patrick opened up the sides of seats to retrieve a deadly power tool or two.

%20(1).jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

The info cards also lay out some of the immersion rules, informing one that if their table gets lit up by a red light, they must move, as the actors are going to use it for a short while, and when their table turns blue, it is safe to head back. It is quite un-instinctive and a little thrilling to stand up and move about the playspace in the middle of a production. It adds a level of tension to the already edgy show. One never knows if they will have to stand up, or even brush shoulders with Patrick Bateman himself.

The show is dedicated to not just production, but to experience. It starts before the show, with cocktail napkins with program information on them, grabbing a themed cocktail at the bar, and mingling with fellow voyeurs. It's fun, one almost feels as though they are in line for a haunted house, or maybe even a rollercoaster, just waiting for the excitement to start.

It is also evocative in some ways of going to see a midnight showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. People were dressed on theme, lots of red and black were sported, and people appeared in sunglasses with a shot in their hand. And perhaps because of this, and Pride month just recently coming to a close, but this viewing brought to light a potential queer reading of the show, or at least lightly touched on some themes that could be parallel to queerness.

Throughout the show, in song, Patrick proclaims he is something "other than the common man." We know of course that this refers to Patrick's incredibly fractured psyche and hellish void inhabiting his consciousness, his amoral and alien nature. However, this acknowledgment that everyone else feels different, is different, potentially speaks to the queer experience. Why am I different? Why do I want things no one else wants? Of course that is not to say Patrick Bateman is queer-coded, or even some sort of allegory for marginalized people. There is, of course, also Luis (Jeremy Allen Crawford), the only explicitly gay character. Luis is one of Patrick's contemporaries and is also in love with him, which he confesses to multiple times, somehow misunderstanding things and feeling Patrick and him have some mutual desire for each other. A contemporary reading of these events stirs up reminders of discourse about gay men fawning over straight ones. And if one wanted to extrapolate further, one could explore the parallels in the show and real life dealing with the relationship between privilege/power, and one's proximity to cis-hetero white men.

Themes of sexuality and identity are so intrinsic to the show due to its source material and protagonist. Patrick Bateman is, in a way, the ideal of a cis-hetero white man. He's perfect, he has a tight body, an awesome job, great taste, and a girlfriend he despises. The show is highly concerned with the intersection of Patrick's identities. In his cis-hetero-white-man-ness, he perfectly represents the world of consumerism, late-stage capitalism, and the insular world of the upper class. Patrick does not care about anyone. Sure he is interested in people sometimes, he reads the news because it's scintillating, but there isn't empathy there. That does not stop him from rambling off things the world needs to fix to be more equitable, he purports women's rights and stopping US foreign intervention, but it's all just a piece in the puzzle of this facade that is Patrick Bateman, it's for show.

His compatriates, however, are both similar and dissimilar. They all care intensely, just about the material, the signaler, the status. They sing vapid lyrics about what clothes they wear, the business cards they have, the fonts, and cardstock. It's funny, it's deadly serious to them.

And the show fortunately does not shy away from the humor. It's evident the director, Michael Windsor understands the show's text, its period, and the shiny and sharp world the piece exists in. There is humor in the horror and horror in the humor.

At the center of both is Kyle Dalsimer's Bateman. The iconic character of Patrick Bateman may seem, in theory, simple to play. He is furious, domineering, curt, and rude. But deeper than that, he is a husk, he is a gaseous abomination of flesh and electricity. How does one play a shell with an incomprehensible internal life? Well, Dalsimer sure does manage. He leads the cast through the show, supports his cast mates when needed, takes the focus with nuance, and confidently handles both fascination and disgust from the audience.

There weren't any weak links in the show, but other performances of note were Jordyn Taylor's Evelyn, which was equally hysterical and interminable, as well as Kaeli Patchen's Jean, who has a lot of responsibility and weight in the show.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Jean, in many ways, acts as a proxy for the audience. She is normal, she is less affluent than the yuppies who occupy the rest of the show, and she has a conscious. She's kind, polite, and accommodating. She is written in a sort of wilting flower way that could be seen as tired to some people but does have this dynamism of being relatable to the audience. She admires Patrick, to the degree of wanting to know him on a romantic level. In some way, is she serving as a proxy to the audience here as well? In some strange way does one admire Patrick? Unburdened by morality, highly privileged, sexually desired? Who's to say?

Perhaps this is what affords him his acts, this admiration, and privilege from the world. Not only can he murder, dismember, and torture, he can confess to it. Throughout the show, Bateman makes offhanded confessions to his girlfriend, coworkers, and anyone really about his acts and desires. It's unclear as to who hears him and ignores him, and who just doesn't receive the information at all. Once again circling back to his identity and social capital. He's a rich white guy, he's the embodiment of a capitalistic hell designed as a utopia. No one takes him seriously, if they did it would be uncomfortable, they might lose clout, they would challenge comfort and power structures. Similarly, he is literally covered in blood for the entire show. He walks the world with his crimes, his trophies, clear on display, and we are forced to look past it, to be okay with it, even when it is wet and fresh in front of our faces.

Speaking of crimes, the practical effects and props involving all this violence and viscera were quite entertaining. There are buckets of fake blood, but also prop body parts (if not mistaken, at one point an eyeball gets squeezed until it pops), and viscera. They are cleverly designed, yarn substituted for guts, at one point Patrick sings with some sort of semi-translucent red slime covering his hands, he plays with the viscera and while the thing clearly doesn't represent a singular organ or body part, the effect is there.

When thinking of blood, one must also think of work done on the part of the costume team (designed by Elizabeth Morton), and the oodles of laundry they must have to do after every show. The costumes did a good job expressing the world of the co-operate 80s, most of the cast in businessware for the majority of the show.

The set, however, was less representational. The walls of the black box theater were covered in clear plastic tarps, expanding upon the motif of Patrick's crime scenes. On one wall, visible to the audience behind the bar, was a projection surface, with projection design by Julian Kelley. The projections were hit or miss. On occasion, a moving image would spend some time on the wall, and would not make much sense. Sure they would fit the black and white aesthetic, but would somehow feel futuristic, or just not of the world of the show or the 80s. Other times they were incredibly engaging: multiple times, especially when Bateman was committing acts of violence, a birds-eye view of center-stage was plastered on the wall, forcing the audience to be complicit in these acts from multiple angles in real-time.

Another moment of inspired design came from the lights, designed by Helen Garcia-Alton. There are multiple scenes and numbers that take place in a nightclub, and while the lights shining down on the stage were evocative, there were lights made to flash on above the grid. The black box space ceiling/ grid and these lights gave the feel of being out in a vivacious nightclub.

What further contributes to the nightlife atmosphere, is yet another unique and strong choice, this one on part of music director Marika Countouris. The show forgoes a band and instead provides a live keyboard and Ableton Live Programming (Abelton Programming by Tobi Osibodu). This provides for, as Countouris calls it a "DJ-style show," which is once again, really fun, and adds another layer of immersion to the piece. We're in a nightclub already, why shouldn't there be a DJ jamming while Bateman performs vivisection?

The music is, as some may expect, atypical of musical theatre. It features a heavily electric sound, at times softer, almost ambient, like an Aphex Twin track, and at others more new wave, closer to New Order. A musical about such explicit subject matter is always full of strong choices, however, there are times when sonically, especially when it comes to vocals, things feel as though they are slightly at odds with the rest of the production. A certain chorus here and there would feel slightly "hey this is a show tune!"

The choreography by Ahmad Maaty is strong when it comes to creating striking tableaus and images, but faces a unique challenge. There are one or two times when the show toes the line of being overchoreographed. Otherwise, the movement is integrated well into the propulsion of the plot, often overlapping with prop and set devices. It's the most frenzied part of the machine, potentially representing the buzzing potential for violence ever-present in Bateman.

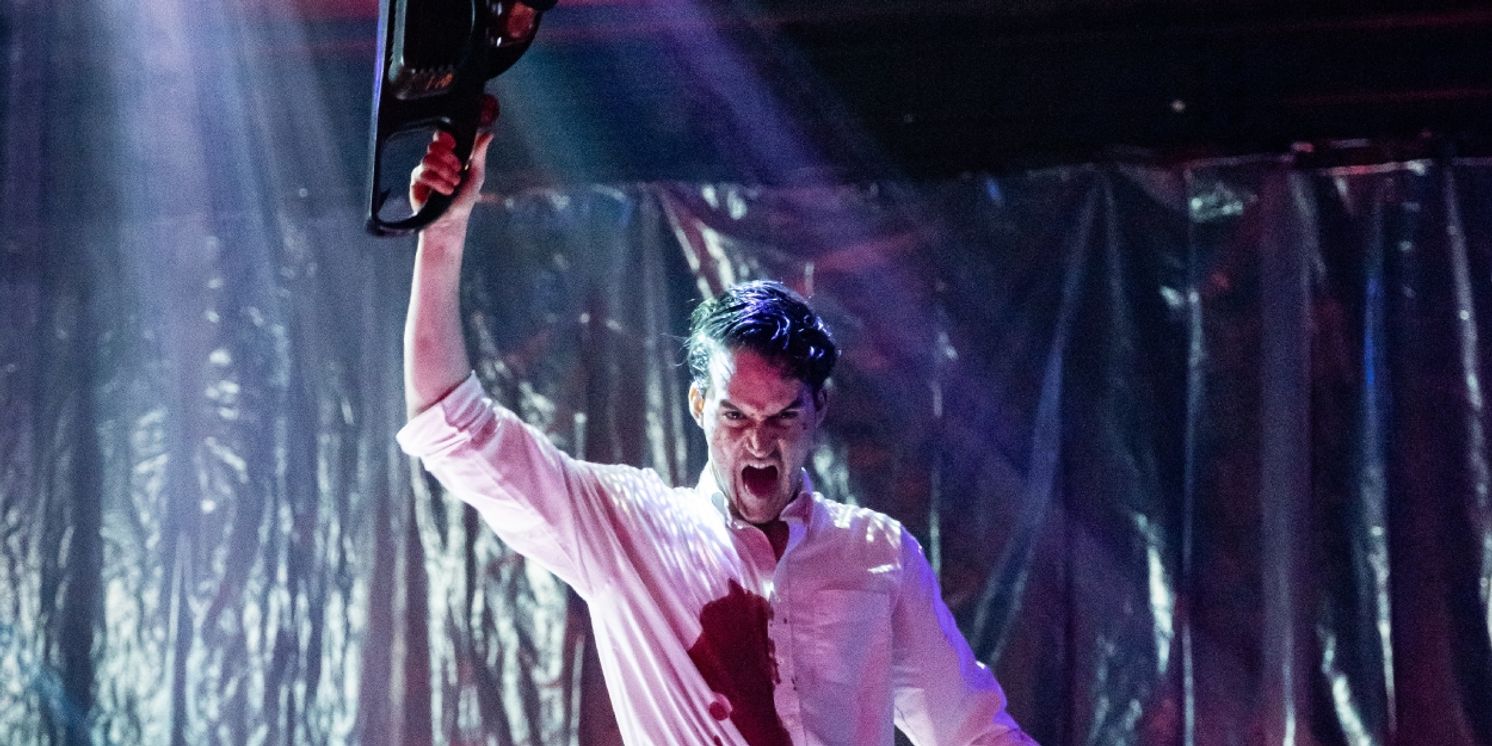

On the note of striking tableaus and images, a truly unforgettable moment of the show comes when, after a killing spree, Bateman stands on a platform, the entire cast, dead at his feet. They twitch and pulsate while Bateman raises his chainsaw above his head, dowsing himself with blood. It's good stuff.

American Psycho is heavy. It deals with intense subject matter and the horror of the reality we all live in. It's also strangely fun and campy. It works. Windsor has more than directed a show, he has created an event, one that is participatory, revelatory, weird, and, as mentioned many times, fun, and not in a shallow way. It's about evil, yes, but also about more, something scarier than evil, evil after all is logical sometimes, it has its own set of morals, but Patrick Bateman has no morals, good or bad. He is not evil, he is inexplicably violent, he is chaotic, he is repressed. The world of his psyche is on full display and creeps into the seats and songs. Local theatergoers would be remiss to miss this production, and Broadway World highly recommends the "Psycho Experience" for those willing to get a little out there.

Information on the show and tickets can be found at Monumental Theatre Company's website at monumentaltheatre.org.

Reader Reviews

Videos