Review: XENOS at Eisenhower Theater, Kennedy Center

The Akram Khan Company presents Khan's final solo performance through November 20

The acclaimed dancer and choreographer Akram Khan has been touring what is billed as his last solo work, Xenos. It is about the one and a half million Indian soldiers who fought in World War I. More broadly, Khan writes, it is "about our loss of humanity" through the present day.

To describe a work about the alternating bombastic horrors and monotony of warfare as bombastic and monotonous is a tautology. Yet I can describe this 65-minute piece, which felt about 24 times longer, in no other way. Technically innovative, atmospherically ambitious, cohesive in its vision, it was assaultive in a grandly existential manner. Yet, one comes away from the Kennedy Center's Eisenhower Theater feeling less that Khan and his musical and other creative colleagues are lamenting inhumanity than that they are seeking vengeance for it through a perpetuation of pain. If that's what you're into, you have through Saturday to strap in and enjoy.

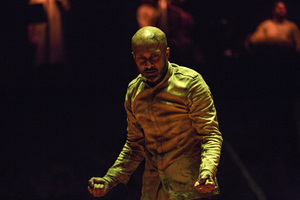

There is certainly no lack of talent. Khan, a 47-year-old Englishman of Bangladeshi descent, interestingly melds Indian kathak traditions with contemporary movement. He has an impressive presence, great speed in his frequent turns and tumbles, deeply expressive arm and hand gestures, and a skilled pantomimist's story-telling pathos.

He inches up and down and hurls himself around Mirella Weingarten's ingenious set -- a versatile incline that, with ample ropes, rubble, dirt, some chairs, and a gramophone horn that doubles as searchlight, can suggest hill, trench, ditch, mythical mount, and hellish chasm. Five accompanying musicians hover ghostly in the background as Khan's protagonist, a dancer, lives through the perfunctory soldierly drills and the violence of the war. A muttered skeletal script by Jordan Tannahill establishes a general air of apocalypse and the roll call of the dead.

All this is quite moodily effective. But beyond his being a dancer thrust into the chaos of conflict, the lead persona has no particulars. He is an everyman, but an everyman veers perilously close to a no man.

There are memorable moments, like a transition of ankle bells to chains and then to an artillery belt. Or the hapless hero's engaging on the summit with the horn of the gramophone, a Beckett-like tenuous connection to an elusive elsewhere through a bit of comically touch-and-go wiring. He wraps rope, in a manner resonant of Magritte, into a mass around his head, suggesting muddled, primordial, disoriented thoughts and dreams.

But with no more-specific backstory or context, this symbol of bewilderment amid inhumanity comes across as just that, a cipher. And it's hard, emotionally, to feel for a cipher.

Vincenzo Lamagna's grating, repetitive score and strident, irresponsibly loud sound design makes it harder. The music at times alluringly melds Indian vocal and percussive timbres with violin, double-bass, and saxophone. B C Manjunath's drumming in combination with konnakol -- a South Indian percussive vocalization style akin to scat singing mixed with beat boxing -- is quite intoxicating. The score movingly incorporates, too, Mozart's Requiem and British and Indian traditional songs into the underlying, menacing drone of its acoustic and electronic bass notes.

But Lamagna relies on the shock of bullet blasts, whistle bursts, and electric screeches to jolt us from long periods of monotonous keyboard pinging and other intermittent scratching clatter. Like the project as a whole, this aural abuse is implicitly justified as essential to the abuse it depicts.

As with the esthetic sadism of the work overall, that justification feels like pretext. There are surely more stories to be told, and wisdom shared, about the futility of war and the scourge of colonialism. But a too-often inhuman depiction of inhumanity offers no remedy, no insight. And without those, what's the point of all this ugliness? It feels like grandiosity and perhaps -- let's just say it -- narcissism in the garb of historical critique, like hostility parading as art.

**

Photo: Akram Khan in Xenos. Photograph by Louis Fernandez.

Run time: 65 minutes, with no intermission. Tickets are available here.

Reader Reviews

Videos