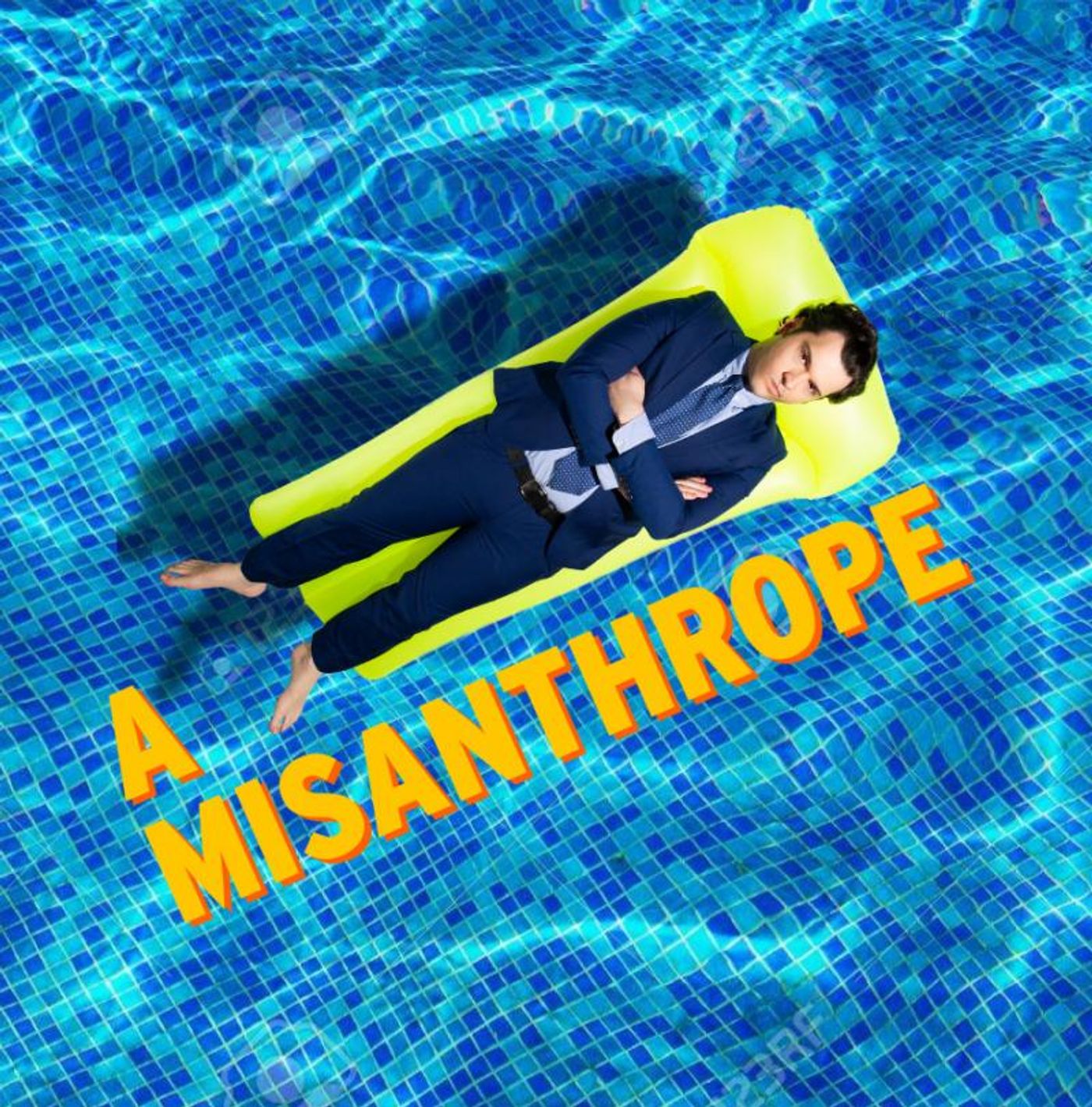

Interview: Matt Minnicino of A MISANTHROPE at WSC Avant Bard

WSC Avant Bard's Script in Play Festival, started in 2016, has been an opportunity to test out shows for full production treatment through the guise of a series of staged readings and post-play discussions. Written and performed by rising professional talent, these readings have led to some memorable productions, including new versions of Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew and Twelfth Night and Lauren Gunderson's hit Emilie: La Marquise Du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight. In 2017, a reading of playwright Matt Minnicino's "distillation" - not "adaptation," as we get into below - of Molière's The Misanthrope was performed. Written entirely in rhyming couplets, it follows a professional cynic who falls in love with an ingenue, and finds his devotion to insincerity tested. Now, it's the capper of Avant Bard's 29th season. I spoke to Minnicino about his career thus far, the adaptation process, and why audiences should be excited for this show.

Note: an essay written by Minnicino about his relationship to Molière's plays is an excellent companion piece for this interview; you can read it on Avant Bard's website.

Special thanks to John Stoltenberg for setting this interview up.

Describe the life of A Misanthrope up to this point. What led to Avant Bard producing it this season?

Let's do this in timeline form!

2016: my friend and colleague Benita de Wit (who I met in the MFA program at Columbia University) asks me if I'd ever wanna adapt The Misanthrope. I say, no way fat chance, and then did it anyway and it was really fun!

2017. Columbia's acting program uses my adaptation in their Molière unit a bit, which is flattering, and I feel like maybe this version could have legs? Or arms? Fingers?

2018: my dear dear friend Quill Nebeker who works closely with Avant Bard asks me what adaptations I have (preference: comedies) so I send him an email that says "Here's an okay adaptation of Molière," and then they do a reading of it and wow, people dig it.

Also 2018: Tom Prewitt, Artistic Director of Avant Bard, asks me if they can do the play and I'm like, hey, yeah!

2019: Woah that's this year! We're doing the play! Megan Behm (wonderful) is directing it, and the cast is stellar.

A Misanthrope was featured in Avant Bard's Scripts in Play Festival in 2017. What, if anything, has changed in the year and a half since?

Ooh this is an easy one because the answer is: not much. The reading in 2017 let us hear which of the jokes were clunkers and I cut 'em, and I also did some tightening. But it's not too different on the page!

A Misanthrope is billed as a "distillation" of Molière's play. What does that mean? And it's "A" Misanthrope, not "The" - why is that?

I think the phrase adaptation is a little tricky when you're talking about texts that weren't originally in English. Whenever a big theatre company does Shakespeare, chances are they've cut the hell out of it and maybe rearranged the scenes, changed the words here and there, deleted or invented a character-but we don't call those adaptations of Shakespeare, they're just "cuts" as one would do of raw footage for a film. This play isn't a translation, because it changes some stuff and cuts some stuff, but it's also not an adaptation because the core of Molière's original is very much there: it's essentially the same beverage served in a different glass and garnished differently. The convention of using "A" instead of "The" for me is a nod to how each take on a classic is exactly that, a take. Mine isn't definitive, it's just my splash in the ocean with these wonderful words and characters! Anne Carson used this technique in her arrangement of The Oreseteia (which she calls An Oresteia) and I've been using it ever since. Shameless thievery.

Talk a little about the adaptation process. You've done Molière, Chekhov, Sophocles, Ibsen - as a playwright, what appeals to you about looking at the classics from new angles?

As a storyteller, I think we must constantly examine and re-examine why stories last. The moment a story-play, book, movie, whatever-is kissed with that enchanted title, a classic, we have a responsibility to not just freeze our examination of it. Is it still speaking to us? How?

I love trying to figure out why we tell a story and how we can keep telling it in a new way. I describe a classic as this ancient bonfire that is big and bright and can be seen for miles, and there are many people who've been touched by its warmth or light, and it's maybe never going to fully burn out. But we as writers have this imperative, I think, to go to that fire and put a stick in it, then Take That burning torch over somewhere where someone hasn't felt the heat of the big fire and light a new, different fire with the same embers. We have the chance to feed a new generation with a story, in small and gentle ways or in huge explosive ways, but that constantly excites me.

Personally, my adaptation process is pretty bespoke though. I get literal translations (aka versions that are clumsy but faithful word-for-word versions of the original), read others, immerse myself, and then decide what I want to do to both make a play feel like it's mine and still honor where it came from. One big thing is I don't like to change the settings or the literal time period even as I'm "modernizing." Like I think the characters in Chekhov or Sophocles can talk in a way that is both mythic and familiar, in tones and colors that sound 21st Century, but still be talking about kings and gods. On a stage, time works differently than it does in reality, and I like to honor and enjoy that.

Tell us about the first play you ever wrote - every detail you can recall.

Oh man, I've been waiting for someone to ask me this. When I was in high school (I went to a Catholic high school in Middelburg, Virginia; go figure) I had a particularly loveable, goofy young history teacher-very Dead Poets' Society-who saw that I got excited about his topics and encouraged me to creatively do my assignments. When we did our unit about Ancient Egypt, I wrote a Dr. Phil-type talkshow episode about how dysfunctional the Egyptian gods were. Kids in the class acted it out, and even though no one was an actor, we all had a great time and I realized things I wrote could bring people joy (and teach them at the same time!). A year later I tried to write a trilogy of plays in verse at age 17 and that didn't go as well.

Who are some of your biggest influences - literary, theatrical or otherwise?

I was raised in Shakespeare, acted in it, read it, saw it, directed it, taught it, slurped it and chewed it and wore it on my back when it was cold. So my big answer is Shakespeare. But I also think my influences shift a little daily, and I realize different parts of my younger life had more or less of an impact than me than I thought. I have been so into Suzan-Lori Parks ever since I read America Play in college but don't think I realized how essential her work has been to me until the last few years. I think Sarah Ruhl's Eurydice, Chuck Mee's Big Love, and Sarah Kane's Phaedra's Love (sensing a pattern?) were the plays that taught me the ways theatre can still be mythic, magical, intimate, horrific, and wonderful.

Right now I'm also really loving being influenced by some writers who are colleagues, friends, or teachers of mine, like Celine Song (her play Tom and Eliza is the best play I can name about love) and Ming Pieffer (whose play Usual Girls is one of my favorite pieces of art about how artists exist in their own work, painfully and beautifully). Consider this my plug for the day, check 'em out.

What's after A Misanthrope?

A lot of fun stuff! Quick list: I'm working on a Very Big and Ambitious adaptation of an obscure Maxim Gorky play called Children of the Sun for my friend Marc Atkinson's Irish/American company Sugarglass, as well as adaptations of Pinocchio, The Oresteia, and Three Sisters. I'm also working on a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure play inspired by 90s point-and-click games, a big play about witches, a play about King Arthur set in rural Virginia, some movies. I'm also headed to our favorite haunt, the American Shakespeare Center, this summer to direct some high schoolers in Richard III.

And, finally - describe the play you dream of writing that you haven't started yet.

I actually have a little email in my draft folder that lists the 5 or 6 plays I mean to write but haven't - it's just the titles. One that's really on my mind is that I wanna write a comedy about The Children's Crusade. On the adaptation side of things, I have fever-dreams about finally doing the stage adaptations of Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, the first dystopian novel, and maybe making it a musical??? Hubris.

.png?format=auto&width=1400)

After this interview, I followed up with Minnicino to ask him a few of his favorite couplets from A Misanthrope:

One that summarizes the play well:

"In short: when caught in nets that we adore /

The tears in them ensnare us all the more."

One he calls "the worst," but also his favorite:

"As Carthage was carved up by Scipio, /

I'll raze her, and not just by being quippy, oh."

A Misanthrope begins previews May 30, 2019, and runs through June 30. Performances are at Gunston Arts Center, Theatre Two 2700 South Lang Street Arlington, VA 22206. Tickets are available online here or by phone at 703-418-4808.

Videos