Review: THE LAST EPISTLE OF TIGHTROPE TIME at Tarragon Theatre

Powerhouse actor Walter Borden's autobiographical play dangles on the tightrope between poetry and confusion

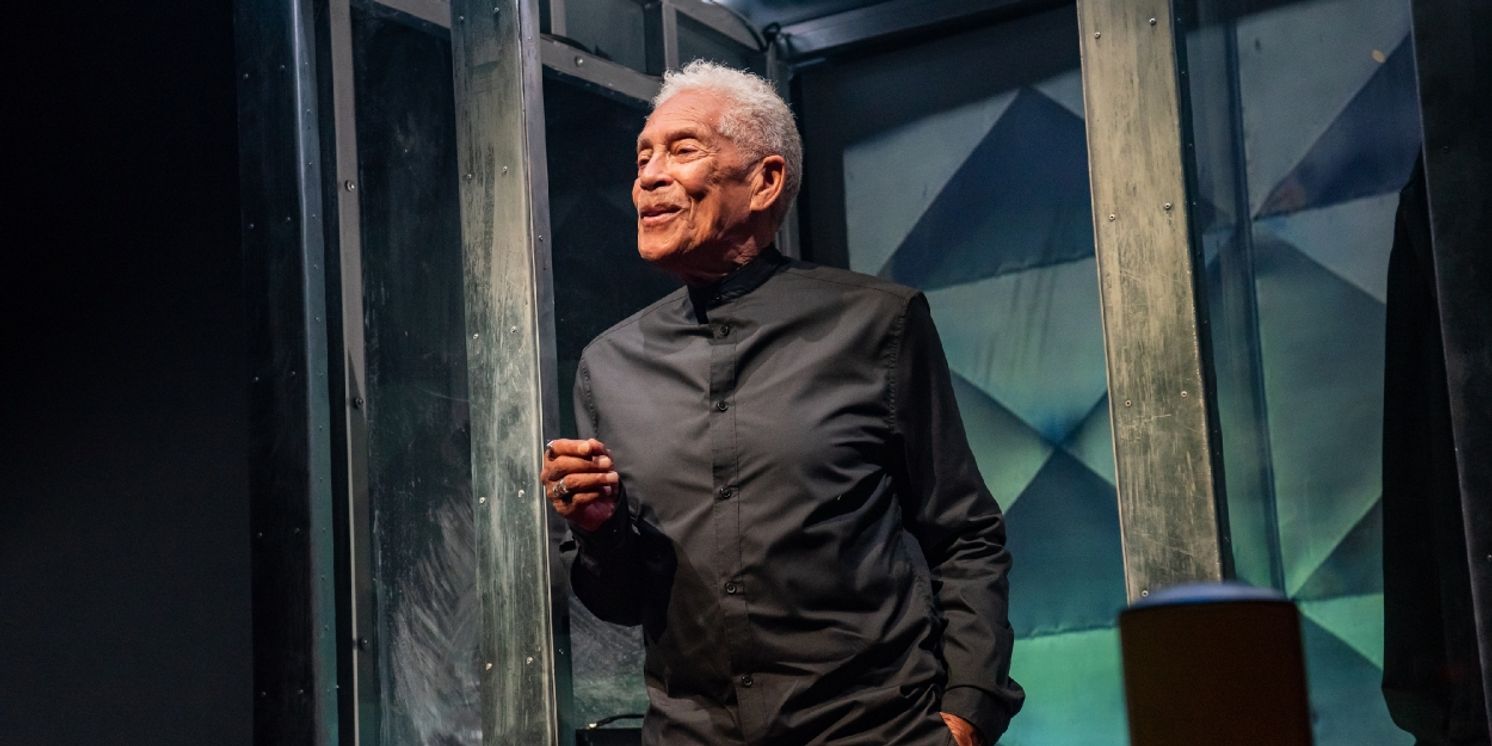

Eighty-one-year-old Walter Borden (CM, ONS) is a powerhouse of a decorated Shakespearean actor, and it shows. His warmly stentorian diction, the welcome drumbeat at the core of his 90-minute solo show, THE LAST EPISTLE OF TIGHTROPE TIME, echoes invitingly through the Tarragon mainspace as he tells stories about his life and commentary about the people he’s encountered along the way.

Like a Shakespearean text, Borden’s complex and meandering autobiographical show about growing up Black and gay in Canada in the 1950s-1970s rewards careful, deliberate attention, and demands a reread to fully understand all of the text enclosed within. An update of his 1986 work TIGHTROPE TIME AIN’T NUTHIN’ MORE THAN SOME ITTY BITTY MADNESS BETWEEN YOUR TWILIGHT & YOUR DAWN, it’s not always the easiest work to follow, but Borden’s magnetic presence serves as a mesmerizing anchor in a sea of non-linear content.

Entering through the audience, Borden demonstrates through his carefully measured ascent to the stage that the hallmark of an accomplished actor is to find fascination in the mundane. Proceeding into what looks like a ticket/toll booth (or religious confessional booth) in the centre of a mandala-like bright circle on the floor of the otherwise very dark and foreboding space, he offers insights on 20th-century culture as it relates to presentations of Blackness, along with its ownership and commodification.

The central booth is often transformed via a series of eye-catching projections by Andy Moro, running the gamut from rap videos to a starry sky to cloth to more abstract images, to a recording of Borden’s head intoning spiritual pronouncements. The shifting imagery is alternately comfortingly homey and distantly beautiful, adding to the dream-like feeling of the show, and is joined by projections on the back wall. Side seats may not offer the best view of the booth’s projections, so it’s ideal to sit in the centre.

Borden focuses on the concept of life as a quilt, with numerous pieces that must be stitched together to fully see the picture at a distance. He stitches his quilt together with heightened, poetic language, which he uses to describe incidents in his life such as the sudden accidental death of a childhood friend and the midcentury sexual abuse of gay teens and young adults in Montreal. The words decorating these scenes are full of the joy of creation; they’re arresting and often heartrending, weaving through the events like a thread of fate without end.

It’s easy to get lost in the language, and that’s both a feature and a bug. The script for this updated version was supposedly perfected over many years, and it feels as though the team, currently headed by director Peter Hinton-Davis, has gotten so used to it that they don’t quite realize that, for most people, this is their first kick at the can. There are moments in the play that are extremely straightforward, accessible, and thoughtful; for example, a moment where Borden plays a prostitute who triumphantly sees to her daughter’s success through her own hard work is a major highlight, a funny and engaging breath of fresh air (the character deserves her own play). But there are also many moments that submerge the audience into a conceptual mass, encouraging us to make our own significance out of the events, but not giving us enough clarity in the material to do so.

The second part of the issue is that, while Borden does an excellent job breathing life into the characters, there’s not enough information between the character switches to shed light on why we are suddenly watching a different character, and how closely this character is related to Borden’s own story. We flip back and forth between life stories and moments of commentary, without it being delineated when one ends and the next begins. Sometimes characters comment on Borden’s story, sometimes Borden comments on his own story, and sometimes Borden comments on other people. To quilt everything together more neatly, it might have made dramaturgical sense to make a clean, consistent break, with Borden telling his story, and the outside characters being the “Greek chorus” of commentators. On the other hand, life is messy, and doesn’t always hand you a specific message, plan, or linear series of events.

It's hard to tell if the booth in the centre of the maze is supposed to be a place of final judgment, or if it is merely a stop on the road of life and whatever comes after. THE LAST EPISTLE OF TIGHTROPE TIME invites you to make that decision for yourself. But whatever you decide, it’s easy to be enthralled Borden’s tremendous presence as he dangles on the tightrope between poetry and prose, pleasure and pain, and clarity and confusion.

Photo of Walter Borden by Cameron Johnston

Reader Reviews

Videos