Review: NO ONE'S SPECIAL AT THE HOT DOG CART at Theatre Passe Muraille

Solo show serves up life advice and stories of street meat

“Everything I needed to know about emergency response, I learned as a teenaged hot dog vendor in downtown Toronto,” says Charlie Petch (they/him) near the beginning of their solo show at Theatre Passe Muraille, the delightfully-named NO ONE’S SPECIAL AT THE HOT DOG CART. Petch, who has at times also been a 911 dispatcher, an emergency room front desk clerk, and a hospital bed coordinator, started their working life in the early ‘90s serving up hot dogs from an unlicensed cart across from the Eaton Centre at Yonge and Dundas, with late-night shifts near the heart of the Village at Church and Gerrard.

As a vulnerable pre-transition teen, with what they assure us in the show’s opening was a “very nice rack,” Petch attracted the attention of the local pimps, prostitutes, and unhoused residents of the downtown core. Some wanted to protect Petch, some wanted a friendly, captive audience for their stories of woe, and some wanted something darker than a can of cola and some street meat.

Petch’s show blends stories of their experiences from behind the hot dog cart to behind the hospital desk with a discussion of the principles of de-escalation, along with highlighting incidents of when they feel they failed to properly follow these tenets. Most people, they assure us, just want their feelings listened to and validated, but it isn’t always that easy. In turn, the show itself invites us to listen and witness; the unpolished sweetness and vulnerability of the storytelling give the experience an informal, intimate feeling that’s reminiscent of the best of the Fringe Festival.

NO ONE’S SPECIAL feels most distinctive when it’s detailing the lives of people who are ignored or deemed disposable by a large swath of the population; ironically, when no one is special, that means everyone is, as well. Petch sketches verbal images of these people with flair. There’s Frank, the unhoused man who steals video tapes at the Eaton Centre to sell on the street, whose resentment over his divorce and the loss of custody of his daughter boils over into a dangerous obsession with Petch once they start providing him with a listening ear.

As a counterpoint to Frank, there’s another unhoused man, who might appear more dangerous, talking in a largely nonsensical stream of consciousness, but often serves as Petch’s bodyguard and never causes them harm. There’s the prostitute that vehemently disabuses Petch of any notion of joining her career path, and, later, the man in Petch’s emergency room who Petch belatedly realizes had a right to be scared about a horrifying health complaint, even if it wasn’t life-threatening enough in comparison to land him at the front of the queue. Even when the characters are making Petch’s life miserable, they always treat them with a sense of compassion, reminding us that “homelessness is a hard job.”

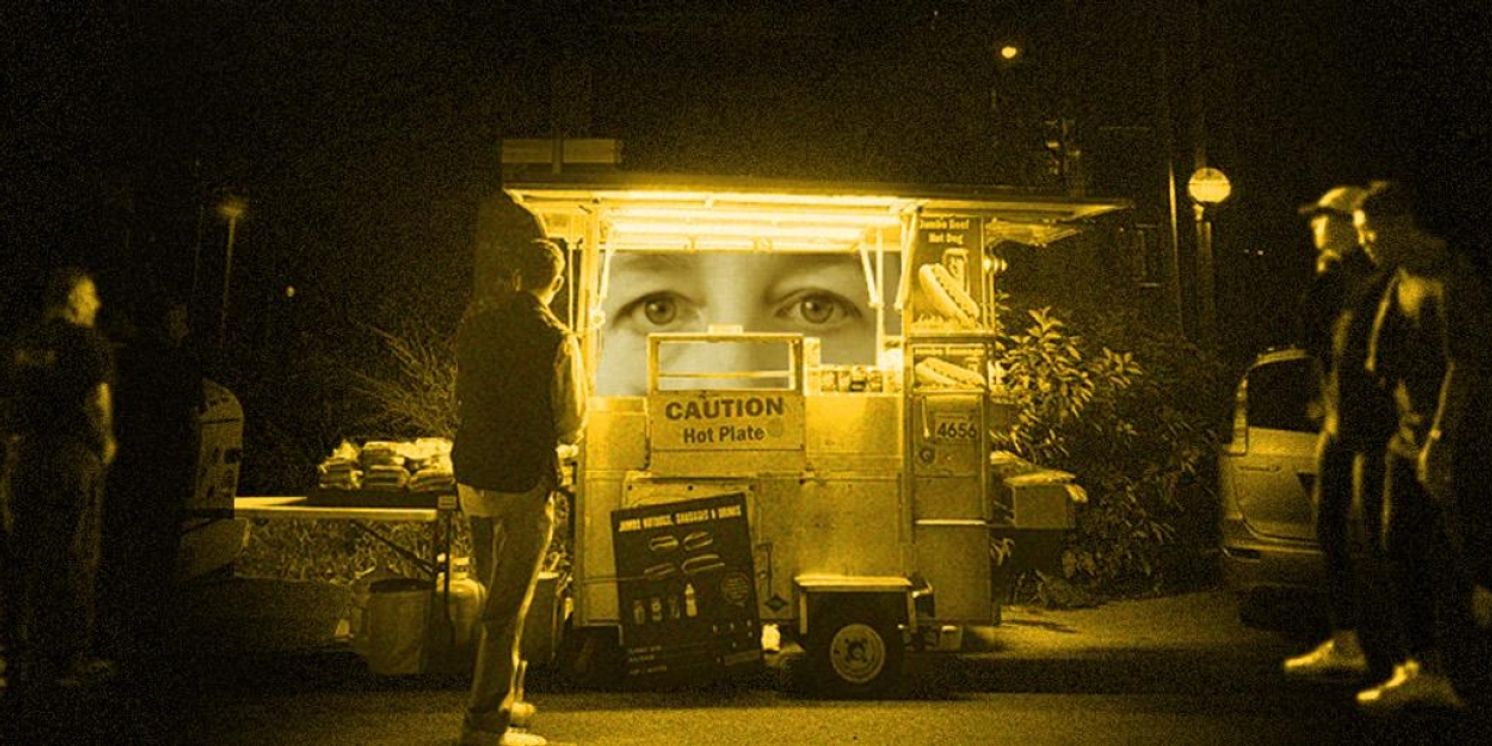

NO ONE’S SPECIAL could benefit from a more interactive use of its nostalgic, realistic set by designer Joel Richardson. The excellent design of the ‘90s hot dog cart, with its matching ‘90s prices (but without corn relish, as Petch regularly shouted at customers expecting the deluxe, licensed-cart experience), along with poles sporting the appropriate street signs and street detritus, will transport you back to a time with far fewer condos and a different skyline.

However, while I’m not necessarily advocating for hot dog Smell-O-Vision, the cart as used feels more like a stationary set piece than a living part of the show, and there’s a lot of stage space between the two vending stations that feels like it could feature more active engagement.

Petch has to walk all the way over to a section of stage off to the side near the front in order to perform the most overtly theatrical sections, which involve using a loop pedal to create soundscapes involving the growls of their repeat customers, a bit of humming, and makeshift instruments such as a singing saw. Had director Autumn Smith arranged a smaller playing space in the adaptable confines of the Mainspace, it might actually have expanded the physical possibilities of the show.

As well, speaking of soundscapes (sound design by FLAUTIE), opening and climactic moments using the chaotic and buzzing overlaid voices of news reporters could be given more engagement with the rest of the text or its staging for those themes to really come through with impact.

In a moving section that explains why you might wait for hours at a hospital despite the severity of your condition due to a lack of beds, Petch explains that in their time as a hospital bed coordinator, the result of who lived and who died sometimes came down to a simple game of hospital room Tetris. It’s easy to feel helpless in such a situation, even if you’re the one allocating the hospital beds; it’s even easier to feel helpless in the wake of so many sad stories lining our streets.

Petch reminds us, while including appropriate de-escalation techniques for our protection, that there is one thing we can do. “Validation is health care,” they say, and that feeds the soul even more than a two-dollar hot dog might nourish the body.

Photo Collage by Emily Jung

Reader Reviews

Videos