Review: MIRIAM'S WORLD at Theatre Passe Muraille

Theatre Passe Muraille becomes a library in installation about public space

Public spaces in large North American cities are dwindling. The number of places-especially indoor places-where one may simply exist without spending money is small, edged out more and more by sites of commerce. The public library is, therefore, a magical, democratic, radical space; it is a place where knowledge is accessible, work can be done without the purchase of a coffee, and tireless staff can help you with your research, regardless of its purpose. Because of this, the library is also a refuge for those society considers "undesirable"-the unhoused, the underage, the unstable.

Martha Baillie's 2009 book, The Incident Report, was longlisted for the Giller Prize for its look into the life of 35-year-old Miriam Gordon, librarian at Allan Gardens Library. The unconventional, loose narrative was told through a series of library incident reports. Some of these reports chronicled the anarchic behaviour of unruly library patrons; others probed Gordon's interior life, which revealed a painful past related to memories of her book-hoarding, poetic father who sold insurance.

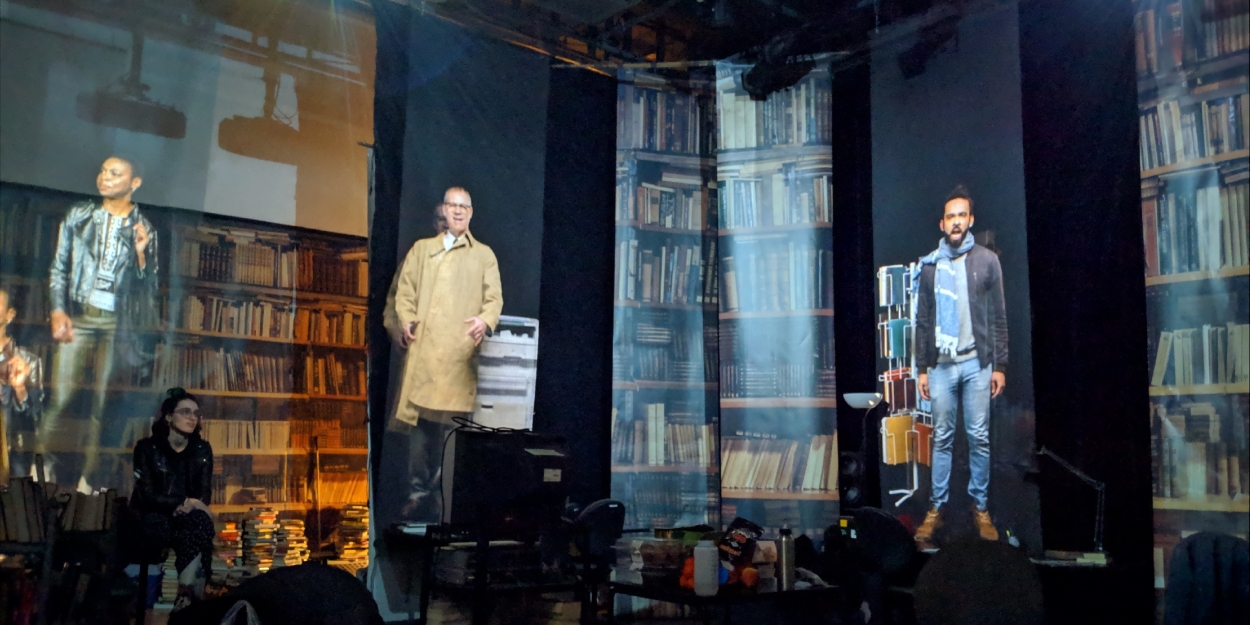

Inspired by Baillie's novel, filmmaker and multi-media artist Naomi Jaye has brought MIRIAM'S WORLD to Theatre Passe Muraille. In this approximately 20-minute video installation, audience members are brought in through a winding path of stacked books into the central library. Handwritten incident reports from the novel are scattered on desks, along with scraps of paper covered with anything from a creepy manifesto to a Passover shopping list.

One can also find notes tucked into the middle of novels, paper airplanes on book carts, and the various other sorts of detritus that might be left behind in a library's throughfare. Surrounding the desks, Miriam and seven library patrons are projected larger than life on vertical panels, as they dance to their own music and interact with each other.

One patron passes out in a toilet stall; another finds inappropriate arousal in the History section; a third proudly announces his upcoming book of poetry. The librarian attempts to keep order among the conspiracy theorists, serial photocopiers, polite young punks, and romantic ideologues, while finding herself in uncomfortable and occasionally nonconsensual exchanges with these lost and lonely people.

Before or after the installation, guests are invited to spend time in the Backspace for Passe Muraille's own "lending library," featuring blackout poetry and other art from the theatre's sponsored community workshops. Even better, you can check out a book of your own from the resident librarian (the book is yours to keep).

The installation is a charming experience in the cozy, homey, yet slightly dangerous feeling it creates via the public library landscape. It's an enjoyable feeling to be in the middle of so many stacks of books, and the transformation of the space into something so vertical and immersive is impressive. The projections are quite lively, drawing you in to the interactions.

As an exploration of the question, "who does the library belong to?", though, it definitely feels more like a Nuit Blanche exhibit than a full theatrical experience. That's completely fine, as long as you know what you're getting into; it's not a narrative or a fully-realized version of an already unconventional book, more a few snippets based on some of its "reports" and themes.

Because of this, viewers will get a very different experience depending on how familiar they are with Baillie's book. Having read part of it in advance of attending, I recognized the characters and the excerpts, which made the world feel more realized. Without this foreknowledge, though, confusion may result, as the installation video itself gives very little context.

To find that context, one must read the incident reports scattered on the desks; luckily, there is time to do so and to let the video loop two or three times as things become clearer. However, I did not notice many audience members doing a lot of reading; many seemed unsure about how to proceed, other than standing or sitting and watching the film once, then filtering out. A more guided directive or clearer clues might have helped effective exploration. Most importantly, context-wise, unless you happen to find and read one particular report, if you don't know from the book a significant reveal from Gordon's past, some disturbing imagery of suicide may be completely mystifying.

When it came to an exploration of the space for the audience, I felt more could be made of a range of items and unusual discoveries, hidden and obvious. Perhaps this makes the most sense in a library, but the discoveries were largely limited to various papers and the stacks of books. The incident reports are mostly piled in a folder on each desk. How much you enjoy going through them will depend on how much you like reading and perusing random stacks of books and papers (if you're me, very much so). I thought there could be more direction and commentary contained within the space itself, even perhaps simply in book placement.

I found myself (perhaps unfairly, as the piece was far longer) comparing this installation to ECT Theatre's 2019 Here Are The Fragments at The Theatre Centre, another production that used a library-inflected installation; that time, to tell the story of an immigrant Black psychiatrist who uses the writings of Frantz Fanon to combat a racist healthcare system and come to terms with his own mental health diagnosis. That show similarly provided an atmosphere of mystery and slight discomfort, used a life's vignettes to interrogate a larger theme, and let the audience take its own path, but it also had enough of a directed structure that the discovery always felt purposeful and the point of view was clear. MIRIAM'S WORLD could make more of its interactive aspects, so that we truly feel part of the public space we're questioning about access.

Photo of Gloria Mampuya, Adrian Griffin, and Tarick Glancy by Maju Tavera

Reader Reviews

Videos