Review: LETTERS FROM MAX, A RITUAL at The Theatre Centre

No-frills play about life, love, and death is gorgeous and sincere.

“God’s an editor, and he’s going to take this draft.”

I’ve been thinking about many lines from Sarah Ruhl’s autobiographical play about her friendship with student Max Ritvo, LETTERS FROM MAX, A RITUAL, over the past couple of days, but none more than this. It fills my mind because it fits into the heart of this heart-filled play so well; sardonic but fond, despairing but hopeful, it’s germane to the play’s themes of grace through writing, rewriting, and the composition of the unfinished self, this act of creation being the closest we get to control over an often unfair and capricious universe. Unadorned, beautifully delivered, linguistically gorgeous and both funny and wrenchingly sincere, it’s one of the most beautiful plays I’ve ever seen, and I think you should see it, too.

Max Ritvo (Jesse LaVercombe) was in his junior year at Yale when he wound up in Sarah Ruhl’s (Maev Beaty) playwriting seminar, his application saved from the “no” pile by her fondness for funny poets and his undeniable talent at being both. Ruhl, a Tony and Pulitzer nominee and MacArthur fellow for such frankly lyrical works as Eurydice, The Clean House, and In the Next Room: The Vibrator Play, immediately found a kinship with the young man.

The friendship the two shared intensified after Ritvo was diagnosed with a recurrence of Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare pediatric cancer he’d already encountered at 16. As Ritvo went through experimental treatments while enrolled in a poetry MFA at Columbia, he became a close family friend of the Ruhls, and kept a regular correspondence with Sarah through texts, emails, and letters as his health increasingly faltered. Ruhl published a collection of their letters two years after Ritvo’s death in 2016, which she later adapted into the play.

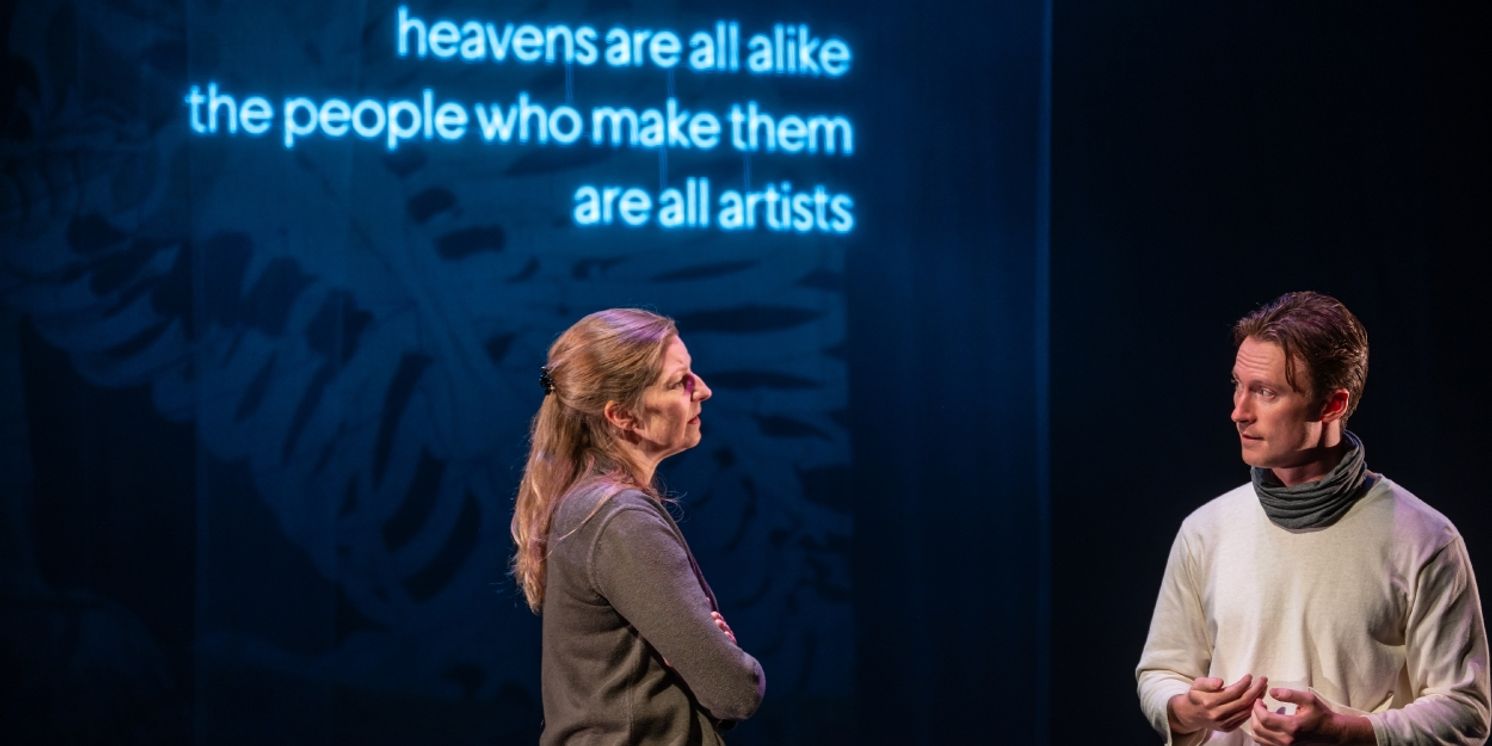

Alan Dilworth’s direction of Necessary Angel’s production has very few frills, because none are needed; the beauty here is in the central relationship and the language around it. Act One involves minimal set design by Michelle Tracey, just two writing desks and a couple of microphones for the occasional poetry reading; Act Two switches the scenery to Ruhl’s straight-backed desk chair and Ritvo’s reclined blue deck chair, flanked by an oxygen tank and a stack of books it suggests are equally vital to Ritvo’s continued survival.

The production goes for suggestion rather than direct representation of illness; LaVercombe as Max changes and slows the way he inhabits his body, but there’s no bald cap or hospital drama, just a sharpening of his pen and an increased desperation in his eye. It’s a play with cancer in it, but it’s not a “cancer play,” and there’s absolutely nothing mawkish or bathetic about it. Ritvo is portrayed as thoughtful, inquisitive, and brave but not saintly, cancer not defining who he was, but refining an already-honed personality.

That’s because the letters and poetry written between the two authors are genuine, mindful, and honest. Full of big questions and tentative, changeable answers, they’re a portrait of two people grappling with change, decay, memory, ambition, mentorship, and love. As fiction, it might feel a little bit much, but the authenticity of the letters, and the way they marry those big ideas with funny observations about daily concerns, ground them at a human level. The humour of the play is also a marvel; it’s hilarious without sacrificing that sincerity, and we’re never laughing ironically at a poem because it’s a poem, but with it because it’s touched something inside.

Both writers seem to carry traces of each other in their DNA, and the mentor-mentee balance is constantly tipping; Ruhl’s father also died of cancer, and as she reads her father’s own final letter to her, we see the recurrence of her pain. A playwriting authority, she’s the tentative one in reading one of her unpublished poems to Ritvo, poetry his domain. Ruhl’s influence is clear in Ritvo’s writing, in particular its elaborate, boundary-pushing and wisecracking stage directions, which he echoes in his final submission to her class before developing his own unique voice. Both cling to language as the only way to fully make sense of a senseless universe (other than soup, Ruhl’s backup cure-all).

For Ritvo, who comes from a faith that doesn’t believe in an afterlife, Ruhl’s lapsed Catholicism and flirtation with Tibetan Buddhism provide two surprisingly similar images of comfort; as Rebecca Picherack’s sparingly-used projections, given three-dimensionality by the use of two screens, tell us: “Heavens are all alike. The people who make them are all artists.”

Beaty and LaVercombe make the letters sound as much like a real conversation as the texts and in-person meetings; even in the midst of monologue delivered directly to the audience, it feels like they’re speaking secret truths into each other’s ears. The show touches on the importance of listening as well as speaking (though Rivko admits that he loves the sound of his own voice) and it’s just as interesting to watch one actor listen as the other delivers a monologue, the reactions quiet but intense. LaVercombe holds court in his intense poetry recitations, while the always-marvelous Beaty runs the gamut between wonder and fond exasperation at his antics.

When they’re actually in the same place, the energy ratchets up a level. A scene where Ritvo, filled with the conviction of the terminal, kindly embarrasses Ruhl over classy brunch with a dedicated recitation is thoroughly charming, as are moments where they dance at his wedding, share soup, or she simply reaches out to hold his foot while he lies recovering from another treatment.

When thinking about LETTERS FROM MAX, comparisons to Coal Mine’s recent excellent production of Adam Rapp’s The Sound Inside are inevitable; both are two-handers featuring a female writing professor at Yale and her eager male student, with whom she develops an intense bond over their love of language and thoughtful approach to the universe. Both shows feature one character facing death from cancer, and trying to choose the shape of that journey with the use of complex, gorgeous language. And yet, while Rapp’s play is dark and often cynical, Ruhl and Ritvo’s letters are transcendent and bright, their relationship innocent and genuine, a life-changing bond where both yearn to become better and the conflict is simply life itself.

“I think of the afterlife as a place where metaphors are real,” writes Ruhl in one of her letters. “It is so hard for children to stop playing and so hard for adults to begin playing, and what if the afterlife is all play, and a place where love is not in the least disappointing?”

Do yourself a favour and participate in this ritual. In the fond afterlife of this relationship, the playing is eternal, and it’s not in the least disappointing.

Photo of Maev Beaty and Jesse Lavercombe by Dahlia Katz

Reader Reviews

Videos