Review: ASSES.MASSES at The Theatre Centre

Marathon game about a donkey revolution is an ass-tounding experience

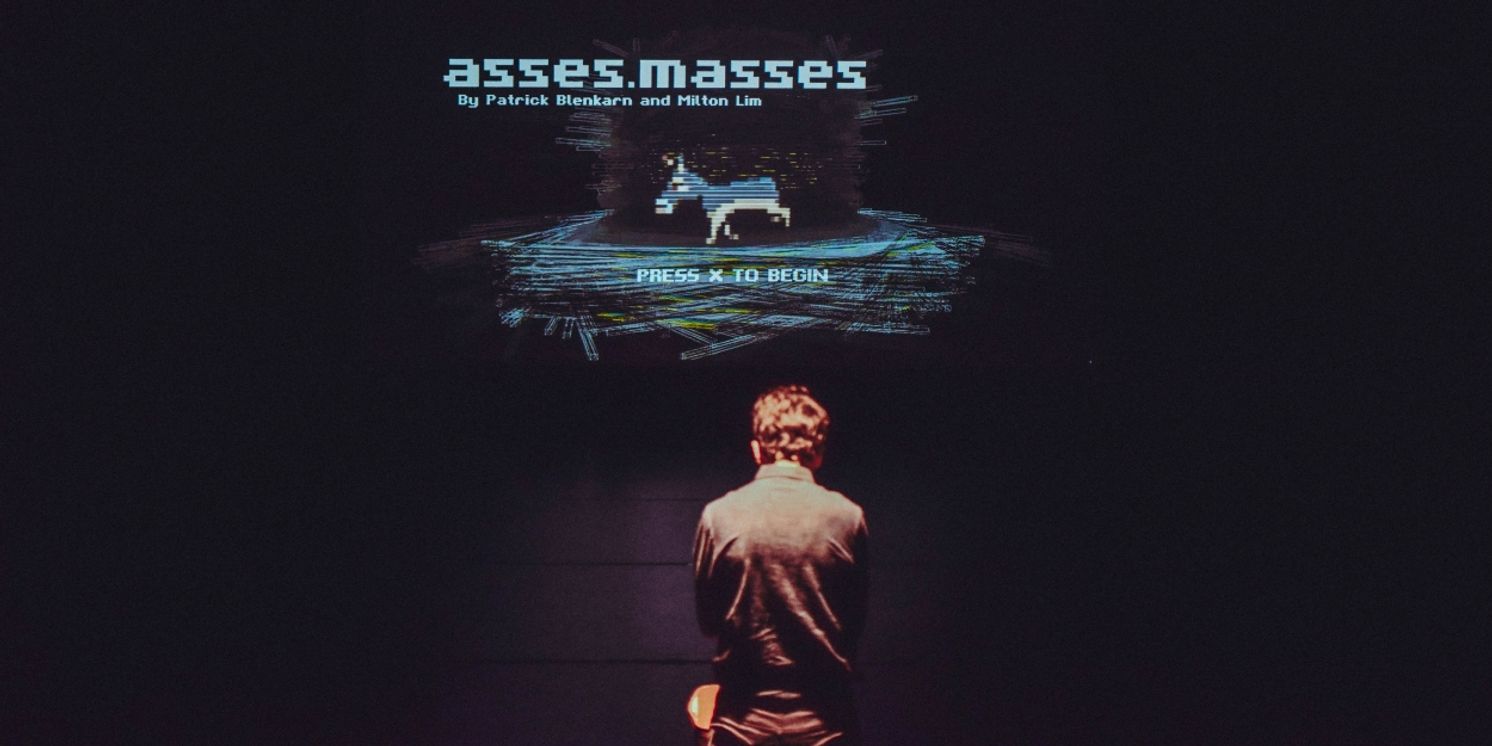

Choosing to attend asses.masses at The Theatre Centre is a big commitment to an intriguing premise. The show, a collaboratively-played video game with a sweeping narrative about a donkey revolution that attempts to restore the working relationship between asses and humans, has no actors, no guidance except tech support, a total of ten episodes with four intermissions, and takes at bare minimum seven hours to traverse.

It’s a nontraditional theatre experience, reminiscent of hanging out with your friends trying to beat a story-based role-playing game on a weekend afternoon that turns into early morning, as you grow increasingly invested and take turns being the one with the controller or the ones yelling suggestions and encouragement. Only, in this case, you’re in a theatre instead of a living room, and your friends are upwards of 100 strangers.

As creators Patrick Blenkarn and Milton Lim might observe, with their penchant for puns, this is a long ass show. But despite its outward silliness, with its thoughtful messaging, it’s anything but ass-inine.

You ass-emble in the lobby before ass-cending the stairs to witness a banner that reads: “Ass Power!” Entering the theatre space, your adventure begins with a short explanation from the team, and then, that’s it: just a screen, a podium, a single Playstation controller, and 100 audience members holding a collective breath to see what’s next. Who will be the first to stand and play? Will we just be a bunch of bystanders? It’s a meditation on the collaborative needs of both an audience and a revolution; if nobody stands, nothing will happen, and there’s at least seven hours of work to be done.

In our showing, things work relatively smoothly despite some early tech hiccups, with few pauses between players, and nobody taking too long of a turn at the wheel. It helps that the game is designed with many natural ending and handover points after a task is completed. Participation is strictly voluntary, and you can choose whether you want a turn with the controller or not; I refrained, but was happy to shout out answers to puzzles or trivia questions.

At first, donkey-related trivia questions and a series of opinions about social values help “generate our avatar,” and the story begins with our introduction to each member of the farm, as our character, Trusty Ass, gathers the troops for the protest. Eventually, you see things from every donkey’s perspective, including the new foal, born the night of the protest, who doesn’t remember a world where humans worked with asses instead of with machines.

Among them, there’s embittered Hard Ass, whose flashbacks to the mine cave-ins quickly sour his attempts to make peace with the humans; cocky Smart Ass, the logical brains of the operation who keeps desperately trying to sketch a path to the desired revolutionary result as it gets further and further away; Slow Ass, who just doesn’t want to be left behind; Sturdy Ass, a mother figure who extols the value of tradition; and Bad Ass, a too-cool-for-school equine who wants nothing to do with anyone else. The puns and characters are legion.

The graphics are fun, nostalgic, and sometimes quite impressive, ranging from those of a traditional 2D scrolling platformer RPG to a first-person perspective 3D extravaganza. You don’t have to be familiar with all genres of video games to enjoy the visuals and the gameplay, but those who are familiar will get even more out of the references to Guitar Hero-type rhythm matchers and Pokemon-style turn-based battle games—one might say they’re “super effective.” A version of Pong called Rocks was very popular with the audience, which started cheering “Rocks! Rocks! Rocks!” every time it came up. Throughout it all, we solve puzzles, dodge assassination attempts, and kick some ass along the way, while surprising narrative twists keep us on our hooves.

The game itself brings up the curious dichotomy between work and play that plagues the modern condition: each state is a desirable goal, but if taken to extremes, destructive. It also looks at the changing nature of “work” and automation, drawing precarious parallels about the fear of obsolescence between the herd of asses and creatives in the age of AI. The foal, for example, argues that the anti-mechanization revolution presupposes that the previous labour conditions were the right ones, but what about a donkey who wants to play and create instead of performing manual labour? At the same time, the “Astral Plane” (ass-tral plane?) presents donkey heaven as a place of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but a place where some remain unsatisfied without a sufficiently complex task to occupy time between shockingly rhythmic orgies.

While the length of the evening feels necessary to the epic nature of the story, it does lag in its last pair of episodes after an exciting fourth act, and might benefit from some judicious cuts to the action, as a number of people left along the way. The lag time is also exacerbated by the several intervals of indeterminate length. While the concept is interesting in that we see the mechanics of the intricate social negotiation of deciding when adequate time and notice has been given to begin again, the addition of a vegan meal during one intermission slows things down significantly. Given the complexity of the enterprise, I was surprised the organizers decided on a meal that had to be slowly plated for each participant during intermission, rather than something more easily portable–gamer food, if you will.

Ultimately, here, the journey is the destination: while the story is by turns heartwarming, heartbreaking, and shocking, its true ending feels out of the players’ control. Winning or losing, or what happens when we try to turn back the wheels of progress, doesn’t seem to be the tale the creators want to tell. Instead, the message is one of our stubborn (dare I say, mulish) tendency to try again and again in the face of a difficult task and seemingly insurmountable odds. It’s also about the importance of sharing and continuing the narrative with each other in order to change things, perhaps not for ourselves, but the next generation, or the one after that. It’s about the grounding influence of tradition, but also the need to adapt or die.

All of these are important messages, and sink in the more you mull over the experience. At the time, though, it’s such a long investment that the payoff feels a bit of a forced catharsis, emotional and relevant but not quite satisfying as you emerge dazed into the wee hours of the night. What you might really remember, though are the intervening moments of triumph and joy, when the puzzle pieces clicked into place, when the player made a crucial jump, and when everyone played together as one.

Call it a special ass show.

Photo of asses.masses opening screen provided by the company

Reader Reviews

Videos