Review: A POEM FOR RABIA at Tarragon Theatre

This fearlessly creative play is as messy and complex as its themes of colonialism and queer womanhood.

“Time is a puddle/A splash/A drop.”

In Nikki Shaffeeullah’s A POEM FOR RABIA, a collaboration between Tarragon and Nightwood Theatre presented at the Tarragon Extraspace, three centuries of women come together to explore their shared history and the currents of progress and change that shape their lives. Expansive and thoughtful, it’s a fearlessly creative play as messy and complex as the themes of colonialism and queer womanhood it investigates, both to its major credit and minor detriment.

In 1853, Rabia (Adele Noronha) finds herself on an indentured servant ship after being “recruited” by colonial forces, leaving her job as a domestic servant and her secret flirtation with her mistress Anu (Michelle Mohammed) on a months-long journey from India to the Caribbean. Alone, bored, and hungry, she bonds with fellow recruit/captive Farooq (Anand Rajaram), who at first tentatively approaches her for sexual favours but soon falls for her charms.

In 1953, Betty (also Mohammed), Rabia’s descendant, starts work as a secretary in the Governor of Guyana’s office after leaving her family to strike out on her own; she’s faced with the choice of following in the alluring footsteps of her coworker Marsha (Virgilia Griffith) and fighting the office’s unjust “investigation” of the country’s newly-elected independent government at the potential cost of her livelihood.

Meanwhile, in 2053, Zahra is experiencing a serious dopamine drop from the combination of the death of her grandmother and the aftermath of the victory of her movement’s goal to abolish prisons. She finds both the hard administrative work of actually closing the prisons and her attempts to have a baby with her partner Sheree (also Griffith) tedious, and escapes into stomach-twisting fantasies of generations past.

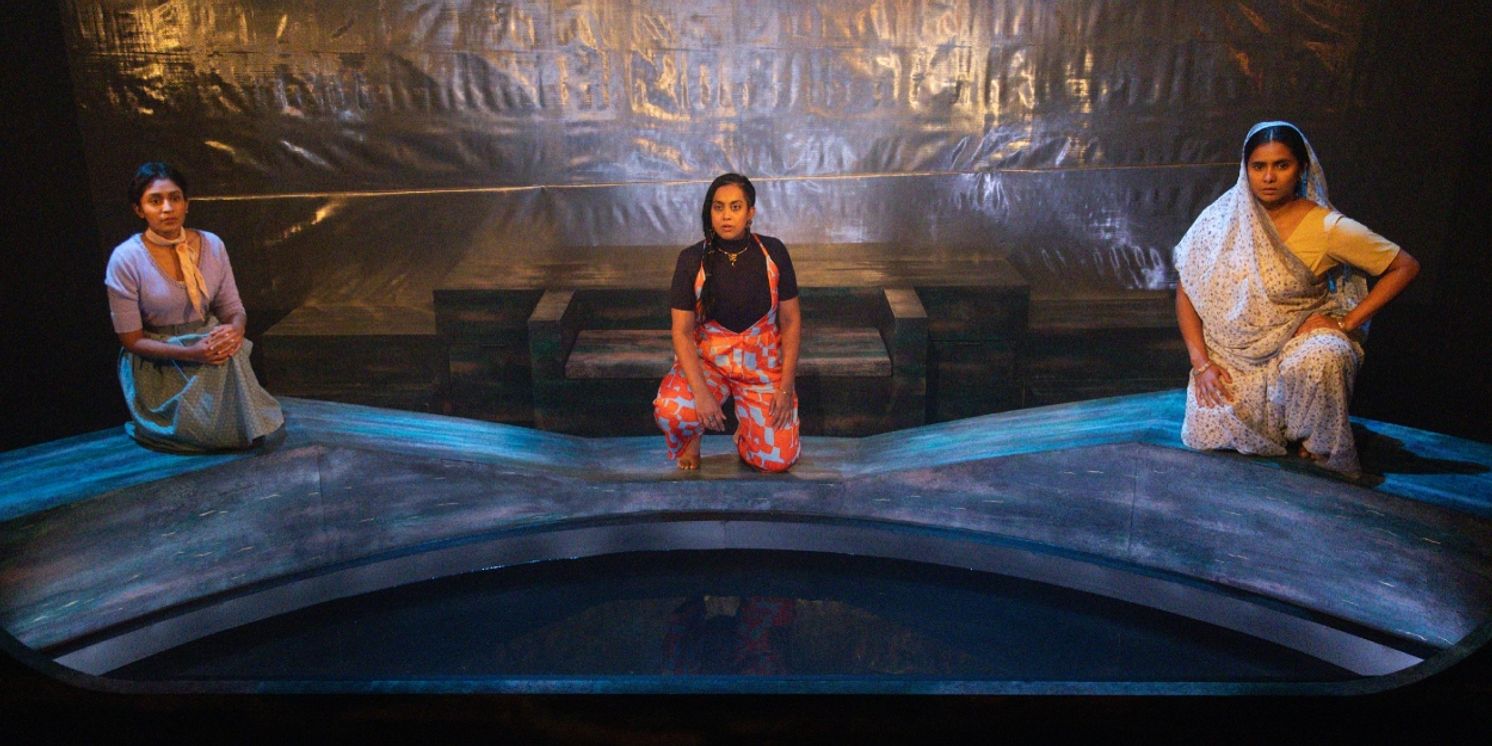

Directors Donna-Michelle St. Bernard and Claire Preuss let everything unfold on Sonja Rainey’s effectively cool-hued set design, which evokes both an office and a ship in its wooden benches, sail-like curtains, and curved bow overlooking a pool of water. The backdrop, asymmetric puzzle-piece panels of what look like brushed metal, form a mirror without a clear reflection. The fluidity of the set allows the marvellous cast to use it to its full advantage, breathing sparkling life into Shaffeeullah’s multifaceted, vibrant characters and allowing them to fold into their pages of history while giving us moments of modernity.

Noronha lights up the stage as the mischievous and lively Rabia, showing us two very different sides of her in her relationships with Anu and Farooq, and it’s hard not to warm to Rajaram’s quietly playful Farooq as the two of them mock the derisive terms the sailors in charge call them. Mohammed’s Betty, a dreamer who fantasizes while listening to radio soap operas, is as winsome as her Anu is crafty and calculating. Griffith’s Sheree and Marsha both alternate between vulnerable warmth and harshness, as people who are forced to carry the weight of the hard work when others let them down. One might wish for more definition from Jay Northcott’s British civil servant, but as a close friend of Zahra, his little-brother-like tough love is endearing.

The cast’s skill is exemplified in three very different readings of the same, titular poem: Norhanha as Rabia, its writer, draws the words out of herself simply, from the heart, speaking personally and tentatively while they blossom around her. When Mohammed as Rabia’s employer takes control of her words, writing them down for permanence, she later speaks them herself, twisting them into a mockery of overblown performance and artifice. Finally, writer Shafeeullah as Zahra gives her rendition the feeling of a prayer, a call to connect generations.

Like a well-constructed vessel, the complexity of the script is its strength when it’s exploring the lives of its characters; Shafeeullah has a great ear for powerful language and scenes that create tension and moral quandaries. However, since she’s trying to tell three complete stories as well as a fourth that brings them all together, there are also a few weaknesses in the symmetry of the ship.

While the 1853/1953/2053 spacing of the characters is effective thematically, logistically there’s a bit of confusion as to how the death of Zahra’s grandmother, a person she admits to intellectualizing rather than connecting with, creates the sudden connection to her ancestors that fuels the plot. A little more information about Zahra’s relationship with her family would be helpful to ground the story’s expansive premise. As well, because the poem is so central to the theme of the play, it feels unbalanced that Betty never really gets a chance to engage with it. The tone and structure of the play also become more experimental in the second half, where either foreshadowing or more of an extreme and pronounced difference would heighten the impact of these changes.

Finally, the choice of 2053 as a setting feels distracting because it appears so much like the present. Without a real sense of what the play’s social and technological vision of the future looks like beyond the recent abolishment of prisons, there’s a sense of untapped potential. Curiously, I had no problem with and even enjoyed the occasional anachronistic language from 1853 or 1953, but felt it was limiting to use present social justice language and talking points, which evolve and change quickly even in the present, in the world of the future.

When three centuries of women literally wade into the water, though, they unlock further depths: a discussion about the value and drawbacks of “presentism” is a major highlight of the evening. Zahra believes in the power of seeing the past through a lens of modern-day attitudes and values to amplify marginalized voices, while her ancestors criticize her for casting their time as a simple narrative of power and marginalization without considering the perspective of the actual marginalized people who lived through it. Everything is messy about history and progress, it seems, even the victories, especially as we get further from the past and it all runs together.

As Shaffeeullah writes, time is a puddle, and it’s up to us to sort out the drops.

Photo of Michelle Mohammed, Nikki Shaffeeullah, and Adele Noronha by Cylla von Tiedemann

Reader Reviews

Videos