Interview: Alexis Spieldenner And Howard Reich of KIMIKO'S PEARL at FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre

Japanese-Canadian internment story told in world premiere ballet

This weekend, Bravo Niagara! Festival of the Arts premieres the ballet KIMIKO'S PEARL. A multigenerational story about the Japanese-Canadian internment during World War II, KIMIKO'S PEARL runs at the FirstOntario Performing Arts Centre in St. Catharines for two performances, June 22-23.

BroadwayWorld spoke to two of the show's creators, Bravo Niagara! Festival of the Arts founder Alexis Spieldenner and Emmy Award-winning writer Howard Reich, about the real-life inspiration behind the ballet, three generations of artistic collaboration, and why these stories need to be told.

BWW: Could you tell us a little bit about the inspiration and the true story behind KIMIKO'S PEARL?

SPIELDENNER: Over 10 years ago, as I was writing my undergraduate thesis, I delved into my own family's history. I looked at the Japanese-Canadian community over four generations, and went into archival research and oral history with my own family. I'm really grateful I had the chance to talk with my grandparents about their experience during the internment, as well as my great aunts and uncles. I had written this thesis years ago, and it really set the stage for the story. KIMIKO'S PEARL is about a fourth generation Japanese-Canadian girl, Kimiko, as she discovers her family's history from the beginning of the 20th century: her grandparents' journey from Japan to Canada through their wartime experiences, and then into the subsequent generation. It looks at my grandparents' generation, how they were able to rebuild post-war, and my mother's generation, how she struggled with her sense of identity and grappled with this painful past.

BWW: So it's an epic story through generations.

SPIELDENNER: Over a century.

BWW: Howard, you wrote the scenario for the ballet. How did you become involved in the project?

REICH: In January of 2021, I retired from the Chicago Tribune after writing for that newspaper for 43 years. During that time, I also wrote several books and several films. When I left the Tribune, I wrote a farewell column. Chris [Christine Mori, co-creator and producer] and Alexis saw that column and reached out to me and asked if we could have a Zoom meeting. So we did, and they said they had a composer and they had a choreographer, but they don't have a story. Would I write the story? We started talking about it, and there were three sources.

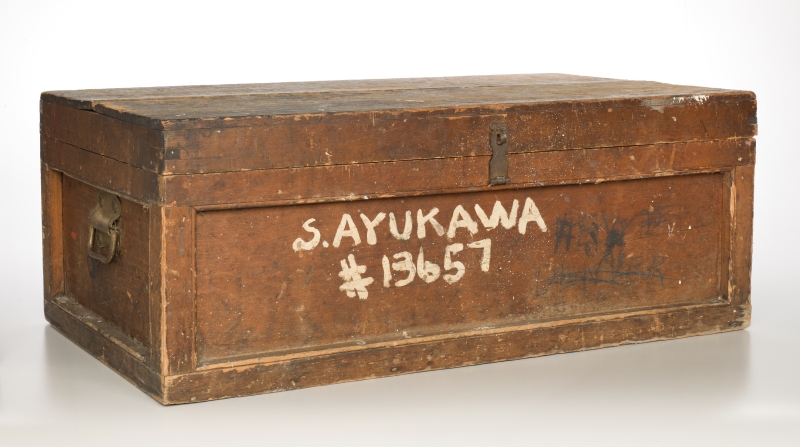

The first was the thesis that Alexis wrote, which really lays out her family's history set against the history of what happened. I combined that with my own experience interviewing many Japanese-American internees, as I did that a lot while I was as a critic for the Tribune, because many of those internees came to Chicago from the West Coast. Then, I also combined that with my own personal sense of being the son of two Holocaust survivors. And that was the sense and sensibility of what I was writing. I had to turn this into a story that you present on the stage. Chris and Alexis had asked me to include three elements: the family trunk, which is pivotal here, the poem that was written by by an ancestor about this experience, and the name Kimiko.

Then one day, I woke up, and I had this vision of this 15 year old girl named Kimiko who goes downstairs in her basement. She's kind of bored and she's rooting around with lack of anything else to do, and she stumbles upon this discarded trunk. She opens the trunk, and in the trunk is a diary. As she opens the diary, the poem is in there too, and this whole story comes to life. And I thought, that's how to tell this story.

Chris had one more idea. She said, can you also work a pearl into this? And so the pearl turned out to be something that was not only in the trunk, but would have symbolic meaning at the beginning and the end of the story and be a metaphor for Kimiko's own evolution and learning of this story. Just as Kimiko discovers the family story that she never knew, so did Alexis discover her family story. And so did I discover my family story in my work as a writer in the books and films I've written, so it's kind of a shared journey that we have. I think is all bundled up into this beautiful multimedia ballet.

BWW: So the story you were writing was specifically for the ballet, rather than the ballet being an adaptation of a story.

REICH: Alexis's thesis was kind of like a spine. What I did was I wrote a scenario for the ballet. That's eight scenes in two acts; what should happen in each of these acts? And then the composer would would compose and the choreographer would choreograph. Over the start of the pandemic, we all added ideas, and that's how it snowballed into this incredible thing that it is today.

BWW: Alexis, what made you choose ballet as the way to express this story theatrically?

SPIELDENNER: So the story has been told through books, films, and theatre, but it has never been told through ballet. This is a universal art form, so we feel that it's really powerful. There's something visceral about experiencing this story through music, ballet, and visual art. It's really a synergy of those art forms.

I think it's also really fitting that the story is told without words, because this is a story that was silenced for many generations. So in a way, it mirrors the fact that Japanese-Canadians are now discovering this story and we're giving voice to it in bringing it to life in a new way.

BWW: Does text have a role in the performance, or is it entirely shown through dance?

REICH: There's a documentary verisimilitude to it because actual documents are projected; newspaper headlines, the poem, and they punctuate what's happening. They help place you in time, but no one speaks words.

SPIELDENNER: That was part of the challenge. What are the elements that we're going to use to make the narrative? And so the visual art aspect plays a really significant role, as well as the family photographs. There are certain moments where we have some really impactful images of my grandmother, my great-grandparents projected. And then also the historic documents. So you'll see government notices projected, and then my great-aunt's poem, entitled "Father's Trunk," that was written in 1992 after the Canadian government's redress agreement.

BWW: I'd love to hear more about the visual art aspect of the ballet.

SPIELDENNER: We are actually featuring three generations of Japanese-Canadian visual artists. Norman Takeuchi was just awarded the Order of Canada. He's experienced the internment himself, he and his family. Lillian Yano Blakey is a third-generation Japanese-Canadian and Emma Nishimura is fourth generation. So it's really been this multigenerational collaboration, and we've all learned from each other, and then learned more about the Japanese-Canadian experience in working together. It's been a really beautiful collaboration. We've commissioned original artwork and they've also reimagined some of their existing artwork for the stage and it's projected.

BWW: Was it a deliberate decision to have the artists represent a multigenerational spectrum to match the story itself?

SPIELDENNER: Yes. We thought that would be really powerful to have those those different perspectives.

%20photo%20by%20Alex%20Heidbuechel.jpg)

BWW: Could you tell me a little bit more about the score, and how the music functions, both musically and symbolically, as part of the ballet?

SPIELDENNER: We've been wanting to commission Kevin Lau for several years, and we felt like this was the perfect project. When we initially reached out to Kevin, this started as a 5-minute musical commission that would integrate family photographs. This was in the early days of the pandemic, and then from there the seed has really evolved into this fully multidisciplinary and large-scale project. Kevin's music is very programmatic. So you really hear the story come to life. It's also unique that he blends acoustic instruments with electronic sound design, and there are also traditional Japanese instruments that you'll hear, such as taiko drum. It will be a fully immersive sound experience, with our sound technology partner Meyer Sound.

BWW: For the digital short that was produced, you tell viewers it has been recorded in such a way that it is best experienced with headphones, for a surround sound or binaural type of experience. In the physical production, will there be a similar experience with the sound?

SPIELDENNER: Aaron Tseng, our sound designer, would be the best one to really explain the technology behind it, but I know for the live experience there will be sonic elements that surround you and certain elements that will actually move throughout the theater.

REICH: As a long-time listener, I've also felt that Kevin's music has a very narrative quality. It is storytelling music. You trace that theme and the theme evolves as the characters do. And sometimes the themes go in unexpected directions, but the whole thrust of his music as I hear it is propelling the story. That's a unique kind of gift to have in the abstract art of music. There's just this vast arc to his story through music; you follow it and it transforms as the characters are transforming.

BWW: You mentioned that there are traditional Japanese instruments involved in the the score of the piece, and there are several generations of Japanese-Canadian artists working on the visual artistic aspect. Are there Japanese influences on the dance aspects, as well?

SPIELDENNER: Well, [choreographer] Yosuke Mino was actually born in Japan but has lived in Canada for longer. He came to Canada to study at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet. He recently retired, but he was a soloist with our Winnipeg Ballet. He describes the style as being contemporary ballet. It's interesting that though he was born in Japan, it was only after coming to Canada that he learned about the Japanese-Canadian internment.

REICH: There is Bon odori dance in the ballet, which plays a pivotal part in the storytelling. It's not simply there; there's a reason it's there when it appears, more than once.

BWW: It often surprises me how many people are still unaware that internment happened in Canada, seeing it as something that only occurred in the United States.

REICH: Well, I can only tell you that it's worse in the United States, because when I told anyone that I was working on this, my colleagues, my friends in here in the US were amazed Canada did that too. They know that America did that, but we think of Canada in a very halcyon view, you know, Canada is the good guys. And when I would tell them, then they were stunned. It was a revelation. So good, let us educate people along the way too.

SPIELDENNER: I think there's this also this misunderstanding, because a lot of people are familiar with the Japanese-American experience, but the Japanese-Canadian experience was so different, especially in the years following, in that the Canadian government forced them to choose between being essentially deported to Japan or moving east of the Rockies. And so that was a second uprooting that happened even after the first one. My grandmother chose to start a new life in Toronto. They were forced to move east of the Rockies, so she actually started over and eventually met my grandfather there. It's amazing to think they had lost everything; they had nothing to return to, and even until 1949 couldn't go back to the West Coast.

So they had to rebuild from nothing, essentially, but that's what we're trying to shed light on is the resilience and the strength of the community. How they were able to persevere and rebuild.

%20photo%20by%20Alex%20Heidbuechel.jpg)

BWW: Is that the main message that you're hoping that audiences take from the show?

SPIELDENNER: I hope that it encourages others to look at their own families' pasts and to have those conversations. To really understand and discover your roots. I think the journey of KIMIKO'S PEARL sheds light on what what it means to be Japanese-Canadian today, and to have that better understanding of your identity through learning more about your own family's experiences.

REICH: Learning that is more than just learning, it's really transformative. It changes who Kimiko is. In the course of this ballet she's a wholly different person at the end than at the beginning because of what she has learned, because of the pain she has gone through to see what happened to her family and understand that. So you learn the past and it changes who you are, and by changing who you are it changes the future too, and so I think that's one of the most inspiring lessons I think of this show. You learn, you transform, and you change the world.

There's a Jewish saying, "Change one person's life, change the world." And that's what I think this show may be on the verge of doing. Because you're seeing it happen--you see Kimiko transform like a pearl.

SPIELDENNER: And it is part of the healing journey, not just for our family, but the intergenerational healing for the community as well to be Telling this story in a new way.

REICH: I think people are going to see and hear something they never have before. Because you're going to see this vast historical story told in a very personal way without words, through movement and music. Anyone in the world can perceive this. And I hope that this show will go on to travel around the world, because the world really needs to see it.

SPIELDENNER: We hope that we'll be able to share it with other communities across Canada and beyond. And the Toronto Symphony Orchestra will actually then be premiering a symphonic suite, Kimiko's Pearl Symphonic Suite, by Kevin Lau, in April 2025. So the story continues.

Comments

Videos