Review: Rainbow Tour of EVITA at Artscape a Qualified Yes, with a Magnificent Eva in Emma Kingston

As far as revivals go, EVITA seems to be produced as often in South Africa as GYPSY is on Broadway, the last major production having played local stages six years ago. South Africa has seen Sharon Lynne, Jo-Ann Pezarro, Dianne Chandler, Brenda Radloff, Anthea Thompson and Angela Kilian tackle the role of Eva Perón, a woman who rose from the fringes of Argentine society to a position of influence, where she championed labour rights, women's suffrage and social welfare. At the time and for decades following her death, her critics labelled her a fascist, a function of her marriage to Juan Perón, who was frequently criticised for his apparent alignment with the principles of that ideology during his rise to power.

In the last twenty years, many contemporary journalists and historians, notably Tomás Eloy Martínez and Felipe Pigna, have reinvestigated those claims, concluding that, possibly, the Perónist policies implemented in Argentina - even those that harmed the country the most - were rooted less in fascism than in the Peróns' interpretation of a range of foreign policies, including the "New Deal" programme in the United States of America. Whether or not one agrees with this position, the Perón legacy is at least being re-examined in as complex a manner as it should be, with many of the current arguments being made in Argentinean voices that balance those from the past, which have primarily, although not exclusively, posited their views from outside of the country.

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

The inclusivity of a greater number of internal voices in tackling many of the routinely accepted truths regarding Argentina's history is a fitting part of its journey away from colonisation. Although Argentina will have won its independence two hundred years ago in 2018, the country's history is proof positive that any post-colonial journey is long and multifaceted, and that much of it is concerned with the restoration of voices that have been silenced. In many ways, the struggle for legitimacy that the post-colonial condition faces is aligned with Eva's conflict in the play - and that without a doubt the reason is why EVITA continues to be resonant in South Africa, with each of its frequent returns to our local stages drawing audiences to the theatre.

Written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, EVITA begins with the announcement of Eva's death, coming full circle by the final curtain. A work of historiographic metafiction, EVITA is narrated by a figure known as Che, who is for all intents and purposes a version of the Argentine-born revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara. As the musical tells the story of Eva's rise to fame, her marriage to Perón, her influence on the political events of the period, the establishment of the Eva Perón Foundation, and her struggle with the advanced cervical cancer that would ultimately kill her, Che narrates and comments on everything. His aim? To convince the audience that Eva's success had more to do with promiscuity than know-how, that everything she did was the effect of style rather than substance, and that the Peróns were corrupt to the core.

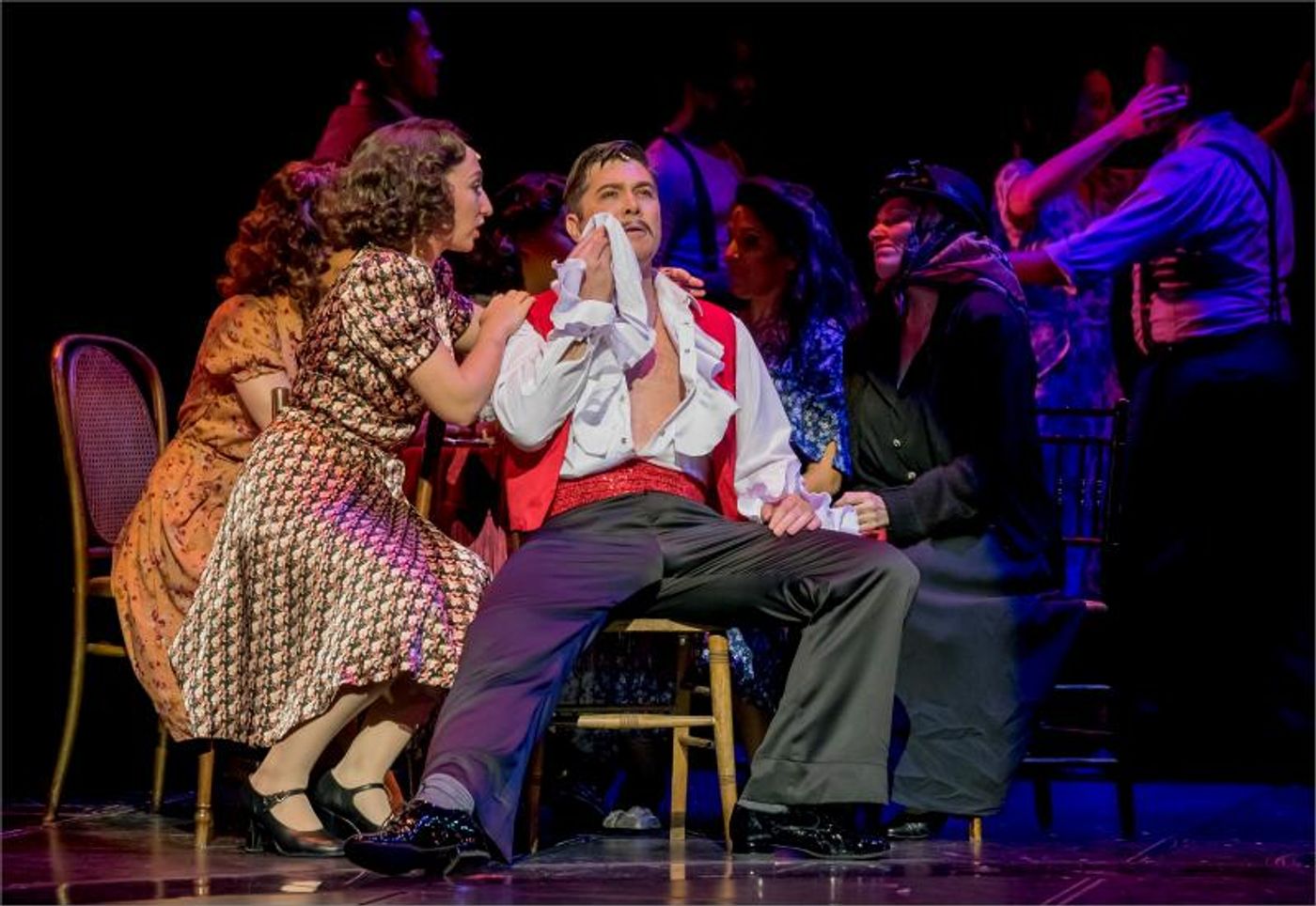

Luitingh as Magaldi in EVITA

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

Much has been made of the announcement that the EVITA currently seen on stage in South Africa is the original Harold Prince production, originally staged in the West End in 1978 and on Broadway in 1979. Famous for its compelling imagery, the production brings to life all of the iconic scenes one knows from old production photographs and the effect is stunning, especially when combined with Larry Fuller's often witty choreography. Prince, when he was at the top of his game, knew better than anyone how to construct a striking tableau and then to manipulate it for its theatricality. The opening of the second act - in which Eva appears on the balcony of La Casa Rosada in her iconic white dress - is just such an example, with the audience seeing the situation from both sides as it shifts from public to private moments, switching seamlessly between spectacle and intimacy. In sequences such as these, his genius is felt on the stage at the Artscape.

And yet, I think the production could have been even better had Prince come out to direct the piece, rather than leaving it in the hands of an associate director, Dan Kutner, whose integrity in reconstructing Prince's work is nonetheless beyond reproach. The difficulty of restaging a historic production lies in the fact that the world shifts, and sometimes the way that something was once said does not resonate as it did in the past. Prince had a first-hand experience of this phenomenon when he attempted to recreate CABARET for its first Broadway revival some two decades after its world premiere. The production failed to have the same impact it had in 1966. With Prince having announced that he hopes to bring this production back to Broadway following its seasons abroad, he should take this earlier experience as a cautionary tale.

company of EVITA in "Buenos Aires"

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

In his original EVITA, Prince created a production that explored, in his words, how 'glamor can mask bad deeds' and that prompted the audience 'to examine what they worship' in the face of dishonest news. Examining our perceptions of the world has become an even more urgent task in the age of fake news, so EVITA is still entirely relevant when taking into account the manipulation of contemporary politics by the media and by politicians themselves. Evaluating our individual perceptions of the truth is just as important. Prince needs to consider how the new light that has been shed Eva Perón on might disrupt his original staging - it has certainly made it impossible to present Che as anything but an unreliable narrator - to create an experience that is immediate, vital and in tune with the times.

There is also the problem of "You Must Love Me". This song, written for the film adaptation of EVITA and added to the stage musical in Michael Grandage's 2006 revival of the show, was not in Prince's original production. While it certainly works as an addition to the libretto, the staging of the number in this production is a misstep. Placing Eva alone onstage in a spotlight to sing the song out to the audience when the lyric demands a personal interaction with Peron is confusing rather than enlightening, and an opportunity to create a meaningful passage between "Waltz for Eva and Che" and "She is a Diamond" is lost.

Kingston as Eva in EVITA

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

If there is any single element that holds this production of EVITA together, it is the casting of Emma Kingston in the title role. Vocally, Kingston's ability to rock the vocals when she's belting out sections of the score that push the voice to its limit already sets her apart from many other actors who have taken up the challenge of singing the role. Her verses of "A New Argentina", for example, are nothing less than thrilling. That she can invest the more lyrical sections of the score with the same kind of integrity is all the better. But no performance in musical theatre can rest on vocals alone, and it is Kingston's acting choices as Eva that make her so compelling to watch. Her Eva is ambitious from the get-go. People seem to struggle in principle with an interpretation of this character that begins with her being so strong, as though a woman's strength automatically prevents one from feeling compassion for her. That said, some actors play Eva that way, their performances lacking the dimension that enables a layered response to the character. But not Kingston. Her Eva may be a shrewd and calculating woman, but not one that is invulnerable. Kingston plays the role without missing a beat, reacting to what Eva experiences as well as what she hears about herself in a manner that challenges one to consider what may be true and what may not be.

This latter aspect of Kingston's interpretation of the role allows her Eva to hold her own against the unforgiving Che, played by Jonathan Roxmouth, who handles the demands of the stylistically challenging score well. Roxmouth shifts between his roles as narrator and commentator effortlessly, mercilessly escalating the character's attacks on Eva as the production hurtles towards its finale. His resoluteness has an interesting if counter-intuitive effect. By the time he is slamming microphones down in front of Eva for her final broadcast, Che appears to be more a petulant toddler than a pertinent revolutionary. His actions create a glorious sense of equivocation that exposes the inherent weakness of binary positions, a layer of meaning that only benefits EVITA in this day and age.

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

The three featured roles of Perón, Magaldi and the Mistress are played by Robert Finlayson, Anton Luitingh and Isabella Jane respectively. Finlayson is perhaps a little light vocally for the role of Perón, and the character comes off rather less imposing than it should - more like one of Perón's 'clutch of stuffed cuckoos' than the man himself. Luitingh, who played Magaldi in the most recent South African revival of the show, is a wonderful Magaldi, making the most of the role's comic potential while also delivering an exemplary "On This Night of a Thousand Stars". Jane is a standout in her single scene, offering a gorgeous rendition of "Another Suitcase in Another Hall".

The only problem with the principal casting in this revival of EVITA - excepting Kingston, whose Argentinian heritage holds her grandfather's first-hand experience of Perón's presidency - is in its whiteness. The casting practices of contemporary productions of EVITA is in the spotlight internationally and the dynamics of how EVITA needs to be approached today are often raised by Project Am I Right, an activist community that promotes inclusive and representative practices on stage and screen. Its founder, Lauren Villegas, recently tackled some of the arguments used to defend the continuing convention of casting white actors to lead this show in an article for Musical Theater Today. The dynamics of casting EVITA in South Africa, where there is no sizable Latinx community, may or may not be different. That is a conversation that still needs to happen. Either way, something does not feel quite right about a production that deals with post-colonialism and which speaks about the resultant revolutions and counter-revolutions using a white mouthpiece. This is not a question about an actor's ability to transform, but rather one about a post-colonial society's responsibility to transform its practices.

company of EVITA in "Don't Cry for Me Argentina"

Photo credit: Christiaan Kotze

There is greater diversity in the ensemble of EVITA, a group of strong performers who, in particular, serves the score well. A tendency of certain individuals to pull focus in the crowd scenes is not curtailed by Richard Winkler's lighting design, which often lacks focus in its contribution to the mise en scène. Indeed the technical creative work tends not to be executed as successfully as it could be. Something certainly went away in Mick Potter's sound design on press night, with the balance between the orchestra and vocals on opening night seeing many lyrics overwhelmed by the music. A return visit to the show later in the week revealed that many of the balance problems had been addressed.

What has stood the test of time is Timothy O'Brien's set design, which resists the temptation to be literal in translating the various settings of the production into three dimensions, a trap into which many productions of EVITA have fallen following the film adaptation. With some sequences incorporating actual historical footage via Duncan McLean's video design work, the production's starkness, its imagery emerging from the darkness, is a masterstroke.

Under the direction of Louis Zurnamer, the score for EVITA sounds glorious. Although they are small in number, the orchestra plays the score sensitively, with some remarkable passages of harmonic richness emerging from the pit.

It is an incredibly fascinating experience watching EVITA in South Africa at this time, particularly given the events that have transpired in Zimbabwe over the last month. This musical will speak to the world for as long as the struggle against colonialism and its legacy of inequality continues. Perhaps in its next iteration in this country, we will see a new staging, built from the ground up, which fully illuminates the show for us and our journey through our specific post-colonial situation. Now that could be something.

EVITA is running at the Artscape Opera House in Cape Town until 7 January, with performances on Tuesdays through Saturdays at 20:00 with additional shows on Saturdays at 15:00 and Sundays at 14:00 and 17:30. Bookings are through Computicket.

Reader Reviews

Videos