Review: COOL BRITANNIA at San Francisco Ballet

The rewarding mixed rep program runs through February 19th

San Francisco Ballet’s latest mixed rep program, Cool Britannia, largely delivers on its promise. The organizing principle is that its three one-act ballets were all choreographed by British dancemakers in the 21st century, thus lending the program a contemporary feel. Wayne McGregor’s Chroma was made on London’s Royal Ballet in 2006 and subsequently performed many times by SFB, though not for more than a decade now. Christopher Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour was choreographed on SFB in 2008 where it quickly and justifiably became an enduring part of the repertoire. Akram Khan’s Dust was commissioned by SFB Artistic Director Tamara Rojo in 2013 for the English National Ballet when she led that company. As an overall experience, I’d liken the program to a happy reunion with two treasured friends only to be interrupted by an intriguing interloper who kind of kills the vibe.

Chroma gets the program off to a smashing start, looking every bit as fresh as it did in 2006, if not quite as startling now that McGregor’s unique style has become more widely disseminated. Joby Talbot and Jack White III’s (of the rock duo the White Stripes) propulsive music sounds like a deconstructed James Bond film score with a couple of piano-based tone poems tossed in to vary the mood.

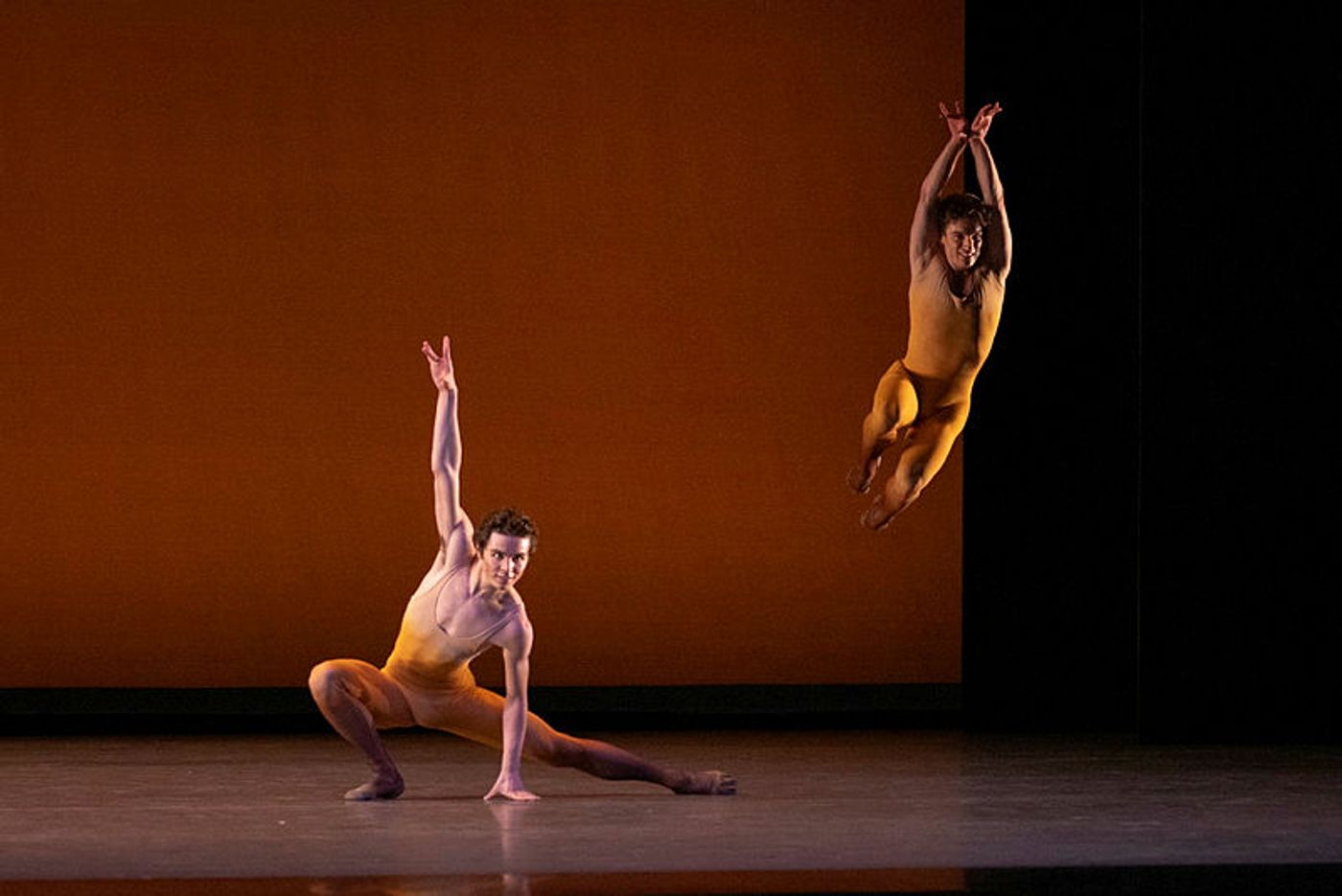

McGregor’s use of extreme extensions, asymmetrical silhouettes and off-balance partnering requires nothing less than total commitment from the classically-trained dancers. The genius in his method is that by pushing the dancers to the max, they are forced to bring their true selves to the performance, thereby revealing their talents in their purest form. The stripped-down visual esthetic of Chroma further amplifies that effect. With the dancers clad in pale pastel camisoles and briefs and enclosed in an off-white set, their natural skin tones are the most colorful thing onstage for majority of the ballet.

On opening night, all ten dancers dazzled at various points, with three of them meriting special mention. How exhilarating it was to see Frances Chung, a sublime technician who danced in the SFB premiere run over a decade ago, tear through the piece with such masterfully calibrated articulation. Victor Prigent’s impeccable line and innate elegance softened the angles of McGregor’s choreography, thus highlighting its unorthodox beauty. Nikisha Fogo seemed lit by an internal fire, sensational in her attack and the sheer joy of her performance. Chroma is a mini-marathon of a piece, and at the curtain call we saw ten very happy, completely exhausted dancers looking like they’d just tackled Mt. Everest and won.

It would be hard to top the sheer energy of Chroma so Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour provided a welcome left turn into less frenzied territory. Set to a succession of seven gorgeous tunes by Ezio Bosso and Antonio Vivaldi scored entirely for strings, this is one of Wheeldon’s more accessible, less formally challenging ballets. It feels like a warm hug peppered with just enough quirk and tension to keep the whole thing interesting. Choreographed on 14 dancers, the ballet is comprised of short dances that complement each other beautifully, including a Celtic jig-cum-tango that is sly and surprising, a rambunctiously reptilian dance for two men and a gorgeously sculptural pas de deux that carries an undercurrent of heartbreak.

The piece looked a little under-rehearsed on opening night (there was a near-collision between two couples early on), but such mishaps will likely be smoothed out in subsequent performances. Sasha De Sola and Harrison James were captivating in the jaunty jig, dreamily romantic and playfully competitive. Luca Ferrò and Dylan Pierzina were charmingly slithery in the male duet, impish and feral as they repeatedly put their ears to the ground as though listening for a portent of things to come. Frances Chung and Joseph Walsh were marvelously serene and completely attuned to one another in their intimate pas de deux.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t so enamored with Zac Posen’s new costumes. While the originals from 2008 were badly in need of a refresh, Posen’s designs were not an improvement. His floaty, chic evening wear in muted tones seemed to fight against what makes this ballet so special, which is its warmth and earthiness. Still, nothing could spoil the ballet’s socko ending where Wheeldon pulls off a coup de theatre that transforms fourteen bodies into a single organic being. It’s mystical, magical, a little weird and rapturously communal.

As much as I love the chance to catch up with old friends, I was especially looking forward to Akram Khan’s Dust in its North American premiere. Created as part of an evening of dance to commemorate the 100th anniversary of World War I, the ballet takes trench warfare as its starting point. Featuring a corps of 21 dancers and one principal couple, the 25-minute piece breaks down into four sections. An anguished male solo rife with writhing and gesticulation gives way to the entire cast coming downstage to link arms and undulate in a fashion that is entrancing if difficult to parse, followed by an extended dance for the women engaged in some kind of intense physical labor and a lengthy and strange pas de deux for the main couple.

Khan’s choreography is inspired by Kathak, a traditional form of Indian classical dance which employs much gesturing and spinning. I found the movement consistently interesting if ultimately a bit impenetrable as none of the sequences seemed to advance the story. The most striking bit was a sort of sophisticated version of the Wave done by the whole cast – super cool to watch, but I had no idea what it was intended to signify in this context. And the final pas de deux is initially intriguing before it wears out its welcome by going on for far too long.

I was equally uncertain about the score by contemporary composer Jocelyn Pook that combines live orchestra with electronica and pre-recorded vocals, including a few measures of “Auld Lange Syne” that are repeated ad infinitum until they became grating. As to what it all means, I have no idea. Perhaps repeat exposures will reveal more depth than I was able to glean for a first viewing.

Dust was undeniably well danced, with the corps showing complete commitment to movement that is not designed to show off their artistry as individuals. The central couple of Benjamin Davidoff and Katherine Barkman couldn’t have danced better, enthralling in their steeliness as they made the cantilevered movement appear effortless. It was exciting to see corps de ballet member Davidoff given the opportunity to take on such a large and demanding role and succeeding at it so completely. He showed he’s got the chops for a major career and is definitely one to keep your eyes on.

At the end of the performance, it was quite jarring to leave behind the death and destruction of World War I only to be met by the clangor of a retro-rock band playing on a raised stage in the main lobby. Presumably this was a nod to the British Invasion of pop music in the 1960s but seemed to have nothing whatsoever to do with the dance we’d just witnessed. I can only imagine that SFB didn’t want to leave the audience on such a downer note, but if that was the case, why program Dust as the closing ballet in the first place? Great art should be able to speak for itself, without need for a happy “button.”

Performances of San Francisco Ballet’s Cool Britannia continue through Wednesday, February 19th at the War Memorial Opera House, 301 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, CA. Running time is approximately two hours five minutes, including two intermissions.

Photo Credit: Reneff-Olson Productions

Reader Reviews

Videos