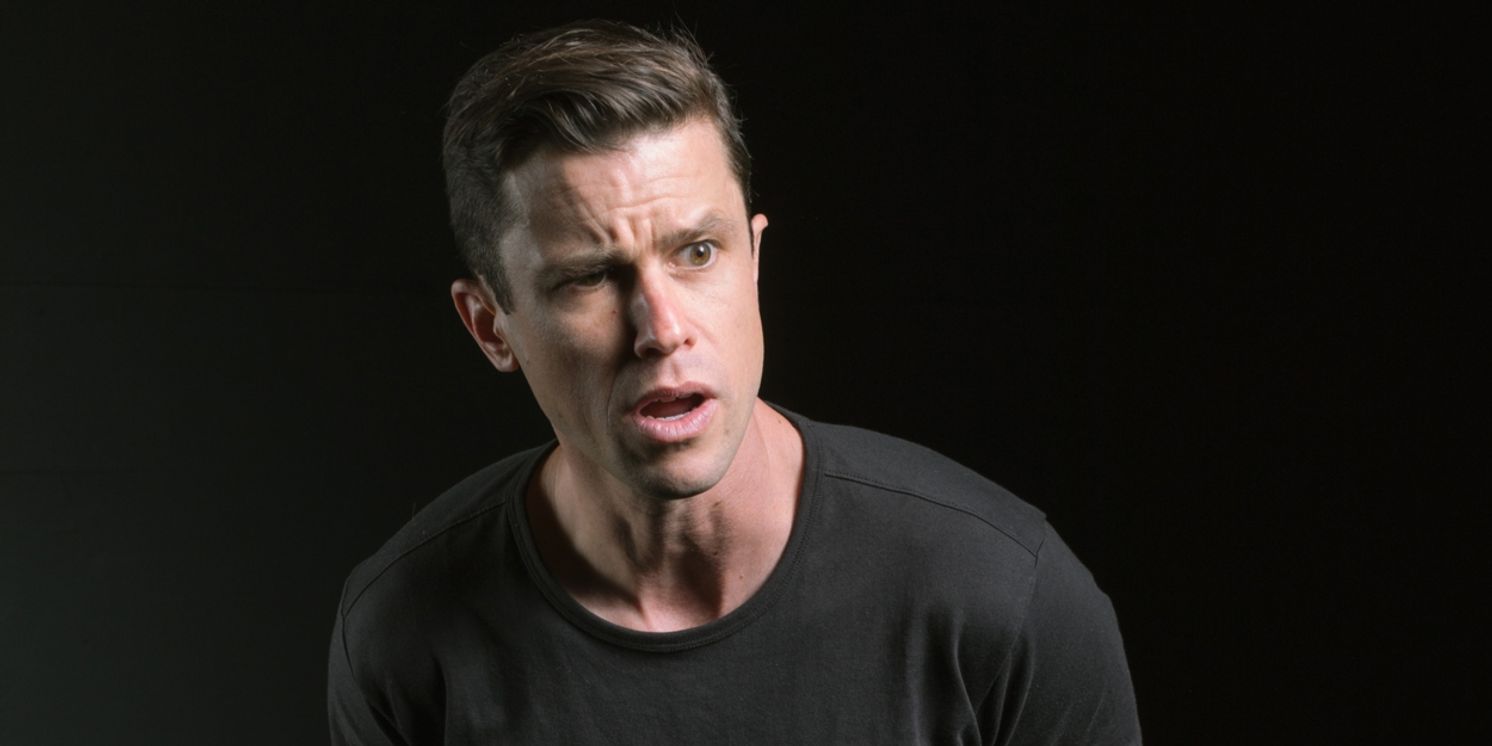

Interview: Dan Hoyle of BORDER PEOPLE at The Marsh Challenges Us to Consider the Ways in Which We Do or Don't Cross Geographic and Cultural Borders

Hoyle brings his funny and trenchant solo play back to San Francisco through November 18th

Sometimes it’s the art that was created to address a specific moment in time that ends up proving to be the most enduring, that only seems to grow more relevant over time. Such is the case with Dan Hoyle’s Border People, which the award-winning actor and playwright has brought back to The Marsh San Francisco. Hoyle originally crafted the piece to address the anti-immigrant sentiment and increasing polarization that seemingly came to a head with the election of Trump. Several years on, those disturbing sociopolitical developments only seem to be getting ever more extreme.

Hoyle based Border People on his conversations and interviews from South Bronx housing projects courtyards, refugee safe houses on the Northern Border with Canada, and travels along the Southwestern Border and into Mexico. It features 11 monologues of people who live on or across borders both geographic and cultural. Border People has been described as an intimate, raw, poignant, funny look at the borders that many negotiate in their everyday lives.

The Marsh has long been an artistic home to writer-performer Hoyle, presenting the world premieres of his shows Talk To Your People (2022) Each and Every Thing (2014), The Real Americans (2010), Tings Dey Happen (2007), and Florida 2004: The Big Bummer (2004). Hoyle’s shows have received praise from the likes of The Huffington Post, The New Yorker and The New York Times for the emotional depth that comes from their having been developed through a process he refers to as “the journalism of hanging out.”

I spoke with Hoyle by phone recently, just a few days after he’d begun this new run of Border People at The Marsh. We talked about what strikes him differently this time around, some potentially doable fixes to our immigration system, the precarious state of American theater post-COVID, what it was like as a teenager to have his Dad away from home in a Broadway mega-hit, and an especially intriguing new show he already has in the works. Given his journalistic approach to creating theater, it’s hardly a surprise that he’s good at talking to a stranger. What is something of a surprise is that he does not at all come across as an extrovert. His responses to my questions were invariably thoughtful, searching, unvarnished and subtly humorous. The following has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

What made you decide that now is the right time to bring Border People back?

I’ve done it out of town a few times and it just is so relevant. There’s ways in which the show has grown almost prescient or eerie. Issues that the show was talking about have become even bigger, more interesting, more complicated. Like this Afghani refugee who talks about when the Taliban was in power, and everyone was so tired of the Taliban when he was a kid. And now there’s a new reality, the Taliban is in power again in Afghanistan, and that resonates.

I created the show in response to the 2016 election. People were drawing harder lines around what it means to be an American and so many people I talk to lived outside the boxes. I got interested in creating a piece that honors the complexity of people’s identities and lives and realities, both those who live on or across geographical borders and borders of identity, borders that are sometimes unseen, social borders in our own country. Now we are heading into another presidential election with the same candidate, and immigration and questions of identity and who gets to be called American are once again largely what this campaign is gonna be fought on, I think, at least on one side.

Are you still in touch with any of the folks whose stories you tell in Border People?

Some of them I can’t be, but several of them I am. Several have gotten to see the show, and that’s always a profound and incredibly powerful experience, for myself and for them. Their stories are just so amazing.

Are there any stories that hit you differently now than they did when you first performed the piece four years ago?

Yeah. There’s Larry in the Bronx who was talking about police-involved shootings when I was hanging out with him in 2016, 2017, 2018. To me it’s very powerful because we all know that Black Lives Matter didn’t start in 2020, but it’s like here is this guy I met who was talking about it in a really complex and interesting and funny way (years earlier). He has family that’s police, he’s been victim of police brutality. So that story hits me, and it feels like there’s something powerful about it being locked in time before all this stuff that’s been happening (more recently). The world didn’t begin anew in 2020.

Have you made any changes to the script?

I cut one monolog because it didn’t feel as relevant. It was the story of a Honduran kid who was kind of a victim of gang violence. Now a lot of the migration is happening in Venezuela and Haiti, so it just felt a little bit like “Hmm, we sort of [already] know that story.” All the other ones are still in, and it’s a credit to the fact that they’re about more than just that moment. I think part of the power of the show was the context in which it came out, in that we were in this very intense and chaotic and in some ways dehumanizing Trump administration. The show was really a complex and joyful humanizing of these stories that I was privileged to be able to experience.

Maybe the only thing that everyone across the political spectrum can agree on these days is that our immigration system needs to be overhauled. Obviously, you’re not a policymaker, but you’re better informed than most of us because you’ve had intensive interaction with some of the people caught in the system. Do you see anything now that might be politically doable to actually improve these people’s lives?

We need to find a pathway to legal citizenship for the 11 million undocumented folks who live in the shadows, and I think everyone sort of agrees with that in theory. I think the right’s answer is kind of like deport them all, and the left is kind of like “We can’t do that, it’s not practical.” It’s also not humane because a lot of those folks really have no connection to the country where they were born. As one of the people in my show says, “I was born in Malta, but was only there for a couple months. All the sudden you’re in your 30s and you get deported back to Malta, and they’re like ‘Welcome home!’ And you’d be like ‘What the fuck?!’”

But it’s complicated. I haven’t talked to as many Venezuelans, and I think a fifth to a quarter of the population has left Venezuela in the last few years. I was in Columbia and there’s something like five, six million Venezuelans that have gone to Columbia. But there still are a lot of folks who want to come to the U.S. and work and then go back, particularly in Mexico. And there’s a long tradition of that, like the Bracero Program. So there should be more work visa authorizations of that type. And any time they've had these massive deportations all of the farm owners are like “I can’t get anyone to work.” You know?

The biggest thing, and it’s much harder, is doing development work, developing civil society infrastructure and institutions in countries where people are fleeing. Development work is incredibly hard, and incredibly hard for the U.S. to do in Latin America because there’s tons of suspicion. In a place like Venezuela where the U.S. has applied these really grueling sanctions, which is making it worse, you also have a government that most people agree is totally corrupt. Venezuela used to have a large middle class and it’s getting completely emptied out.

I got a couple nice emails after the show on Saturday. One was very complimentary about the performance, saying there was one character in particular where he felt like he was seeing this other person. He just started crying and left the theater kind of overwhelmed, and that that it stuck in his mind, seeing this person, meeting this person. I think that’s part of the power of live theater in this form. Not everyone can go and travel to this migrant shelter and meet this person. And this character is this guy who was gay, was born in Mexico but had been living in the U.S. since he was 19 and got a random drunk-driving ticket, got sent to ICE and got deported to Mexico.

But the thing that was hurting him the most was that he had to go back to his family and tell them that he was gay and had HIV. And he was saying, “It feels like I have to go back to the person I was before, and I don’t want to do that.” That’s just so universal. It’s like amidst this complex sociopolitical tangle, everyone can relate to being forced to go back to a person you were 20 years ago.

I think the title of the piece is brilliant in the way it’s so succinct and literal yet carries all these deeper connotations.

I’m glad you like it. People often assume it’s about the southern border with Mexico, but really only a third of the stories are from there. Two-thirds of the stories are from the border with Canada or just, as I say, about the many unseen borders that we cross or don’t cross in our everyday lives. The goal both with the title and the piece is to challenge people to consider the ways in which they cross or don’t cross borders and what it’s like to be a person who is a border crosser, and also talk about the ways in which I think actually we need more cultural border crossing.

Isabel Wilkerson talks about when you reach across the divide of caste and class, every time you do that you break it a little bit. And my work is doing that, right? It’s me going out and connecting and developing a relationship, creating trust with somebody whose story has been overlooked but is incredible and deserves to be amplified. So I think it’s always encouraging audiences “Is there some way you can do that in your own life?” Maybe it’s really small, maybe it’s finding some small relationship with someone who lives in your neighborhood, but is there some way it can inspire you to let go a little bit of your own ego and open your ears and eyes to other people’s stories that maybe are right in your own backyard?

Your dad, Geoff, was in the original cast of The Lion King, arguably the biggest Broadway hit of all time. Even though he’s had quite a successful career, being in that kind of pop culture phenomenon was definitely not his normal gig. As his son, what did you think of it at the time? Was that cool? Was it weird?

Well, I was 17, so I think I experienced it largely the way a 17-year-old would, which was that my dad was gone for that year and so I got to drive the van. The family had a old beat-up Toyota Corolla and a old beat-up Dodge minivan, and I got to drive the minivan for my senior year, which was great. I didn’t crash it! [laughs]

We went out and saw the show, and that was cool, but I didn’t have a huge sense of like “Oh, my dad’s on Broadway, that means something different.” He had done out-of-town gigs before, so for me it just felt like a really, really long out-of-town gig.

You have a couple of kids, and your son is something like 7 or 8 now. Do you have any idea what he thinks his dad does for work?

Yeah, he knows pretty well. Winston, my son, he’ll say, “Mom’s a teacher and Dad’s an actor-playwright.” And I think he even says like journalistic theater. People are just like “Oh, do you just like talk to everyone on the subway?” And I’m like “No, I’m not that extreme.” You know, you pick up somebody’s vibe and if you’re curious you know you start a little conversation. So we end up doing that a lot.

I was just curious because it’s not like having a dad who’s an accountant, or even just an actor.

Yeah, it’s quite specific. I hope I’m able to keep doing this for a while. We need people to come back to theater, that’s for sure. I think we’re all kind of waiting to see is that gonna fully happen, or are we in a different era? Because for me it’s kind of like three jobs. You know, I’m like a journalist, and then I’m a playwright and then I’m an actor. It takes a long time to create it and do it at a high level, and there’s tons of relationships I’m continuing to have with people from the past, and then building new ones in the future. So much of our time is spent doing marketing now, it’s crazy! [laughs] So we appreciate journalists who help spread word.

I talk to theater people all the time and I have to say that everyone is expressing similar concerns. It’s not unique to a certain theater or even a certain level of theater company. Everybody’s going through it.

I feel very strongly about the work that I do. I think it’s actually interesting [laughs], I think it has value in the world, and audiences feel that. I’m always trying to explain it to people, and I think ideally it’s that you have this visceral experience. I have a huge privilege and responsibility to try to share these stories out which people have trusted me with, with the biggest impact and at the highest level of craft, and that’s what I try to do. Every night before I go onstage, it’s like “just honor these stories.” And I’ve done a ton of work as well. There’s a ton of shaping, there’s a ton of body work, a ton of acting – of all this stuff to really try to make it translate and be as dynamic as it possibly can be. It’s trying to honor the folks who shared their stories. Cause I know that they feel honored to have them be shared, so it’s like “Okay, well I have to hold up my end of the bargain.”

Your journalistic approach to creating a piece requires a fair amount of development time. Are you currently working on anything new that you can talk about yet?

I’m working on a new show that is gonna be about what’s going on post-pandemic. I have a title that I’m not sure will be it, but right now the sort-of title is “Fear Rage Heal Change.” I began looking at reconciliation when I went to Columbia for two weeks because they’ve been having this national reconciliation process after the end of their long civil conflict. I was thinking maybe that’s the way out for us in the U.S. because we’re so polarized, so calcified. But then a lot of the people I’ve talked to in the U.S. were like “I don’t know that we’re at reconciliation. We’re still fighting.”

So I became interested in looking at places and people who are trying to move the country forward in really difficult areas, where it feels like it’s so hard. Because in the Bay Area we’re not really on the front lines of this stuff. So I went to Florida where they’re having these school board clashes and the “Don’t Say Gay” laws, and I talked to a guy who is a former violent extremist and who’s been de-radicalizing violent extremists for 25 years. I went and profiled canvassers, organizers with the New Georgia Project, which is one of the organizations that flipped Georgia blue for the first time in 40-something years.

So it’ll be those stories, and then I think there’ll be some other stories about the folks who are maybe going down some of the rabbit holes, you know the fear and the rage that is so at the center of our politics, and contrast it with these folks who are doing this work in such an inspiring way, kind of feeling like people need some inspiration, too.

I really look forward to seeing that piece because our world just seems to keep getting more divisive. I don’t see any way out, and I’m not a pessimist by nature.

I have a pretty strong motor and I would never say I’m naïve, I would say I’m cautiously optimistic or … idealistically pragmatic, maybe? [laughs]. It’s cool to be around some of these people, and as always with all my work, because it’s I hope very specific and well-observed, there’s surprising moments of comedy and just “Wow, this is the world in 2023. Okay!”

(all photos by Peter Prato)

---

Border People, developed with and directed by Charlie Varon, runs through November 18, 2023 with performances at 7:00pm Fridays and 5:00pm Saturdays at The Marsh San Francisco, 1062 Valencia St., San Francisco. For tickets or more information, visit themarsh.org.

Videos