Interview: Hershey Felder of HERSHEY FELDER AS CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN A PARIS LOVE STORY Transports Us to That Romantic City in the 19th Century

The Virtuoso Pianist Livestreams His Hit Show from Florence, Italy on November 22nd

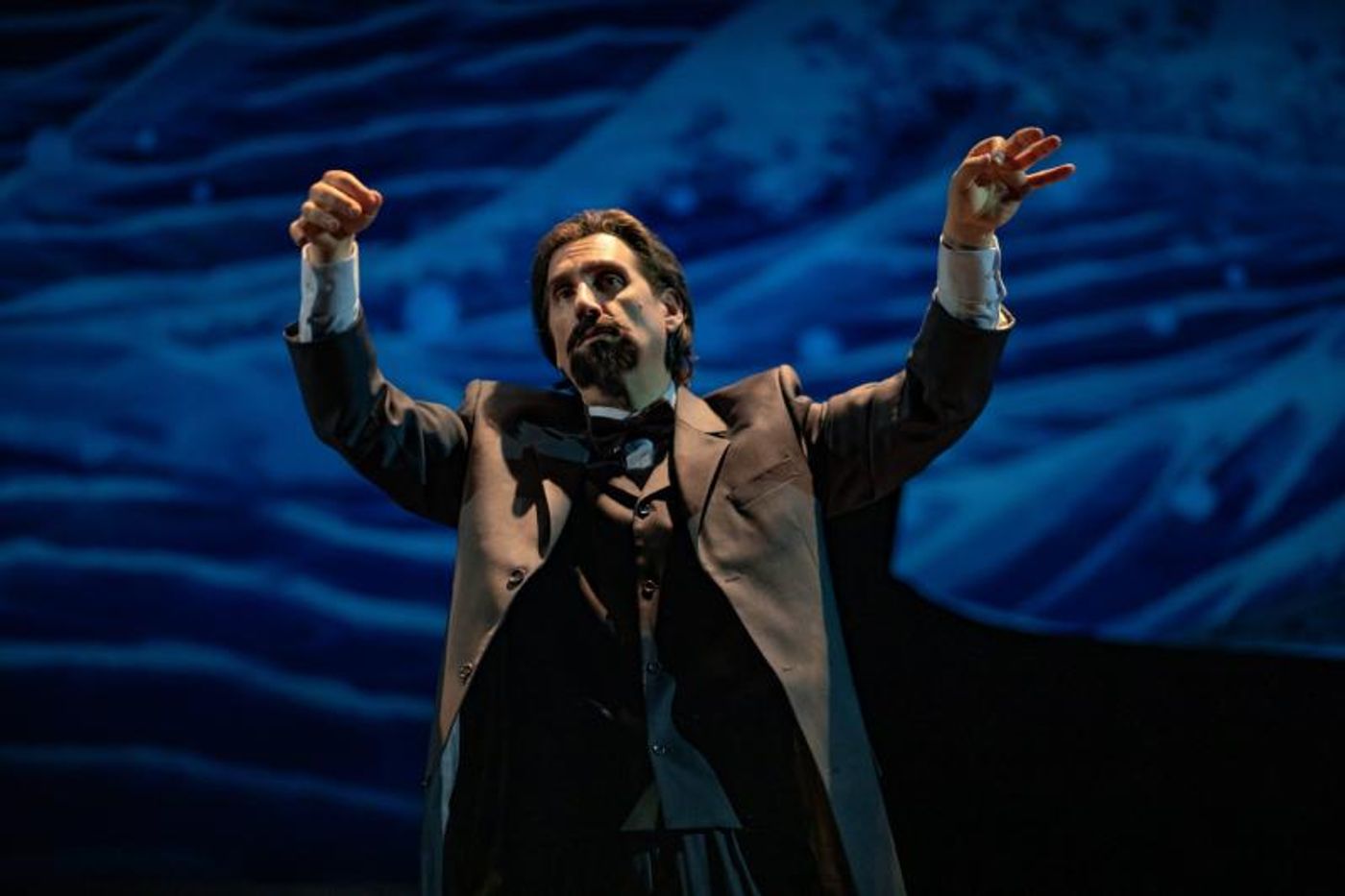

seen here in a previous performance

(Photo by Christopher Ash)

Perhaps it's because international travel is now largely impossible due to the ongoing Covid pandemic, but lately I've found myself longing to be in Paris. I've even started having vivid dreams about it. I suppose if I can't get there in reality, at least I can get there in my imagination. Well, it turns out that virtuoso pianist Hershey Felder has just the thing for our travel-starved souls. On Sunday, November 22nd, he will livestream a performance of Hershey Felder as Claude Debussy in A PARIS LOVE STORY, transporting audiences to Paris without needing to leave home. This musical tour de force takes us to many of Paris's most-loved sites in a personal journey through the life and music of Impressionist composer Claude Debussy, who created music of ravishing beauty, color, and compassion, from the sweeping La Mer to the evocative Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, and the mystical "Clair de lune," ultimately shaping a whole new world of color in sound. Felder will perform the show live on Sunday, November 22 (5pm PST/8pm EST) from a rich, filmic setting in Europe that provides audiences a front-row view of the hit show. Tickets and additional information are available at HersheyFelderLive.com.

I recently had the distinct pleasure of chatting with Felder from his home in Florence, Italy while he was in the midst of preparations for the livestream. [And I mean that literally. His director, Stefano Decarli, made an impromptu "guest appearance" midway through our call!] We talked about his enduring love for Paris, his passion for Debussy, and how he goes about crafting his livestreams. Our chat just happened to take place the evening before the U.S. presidential election, so that was also on his mind. Any conversation with Felder inevitably becomes a free flow of fascinating cultural references, pointed observations and emotional touchstones. As knowledgeable as he is about music and theater, he retains the unbridled enthusiasm of the eternal student. Raised in Montreal, he is a natural polyglot, and I often get the sense he is filtering his thoughts through a variety of languages into the American English vernacular. This can result in an uncommonly musical syntax and a surprising turn of phrase. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I've always had a special affinity for the city of Paris, and I'm certainly not alone in that. What is your own connection to the city of Paris?

Well, I grew up speaking French, it was largely my first language, but studying you know Paris French, not Quebec French. I suppose my connection to Paris in the case of this is my mother always wanted to go there. She was Hungarian, but Paris was her dream city.

Did she ever make it to Paris?

No, no. She died at 35.

And for me, all the great music that I've loved and performed all over the world essentially emerged from Paris, you know if you're talking about Chopin and Liszt and... Just the whole 19th-century romance of Paris and all that entails is so magical. And to me, Paris and Florence are home, they always have been. Even before I had been here, they were home. I always felt like I belonged somewhere in the 19th century and I just got lost. [laughs] Paris was my main home for 12 years, and now it's Paris and Florence, except I can't get there because they've locked everything down, but we have homes in Paris and Florence.

Wow, that's my dream!

I know how you feel. I just made it happen because being onstage and living out of a suitcase 11 out of 12 months a year just wasn't doing it for me. I needed a home, because it was really a transient lifestyle - it isn't now because of Covid - but it's just an awful lifestyle.

A Paris Love Story premiered in the Spring of 2019. Have you reimagined it at all for the livestream?

Yes and no. The concept is the same, but how I execute it is quite a bit different. We have locations this time. We were actually gonna do some live film shooting in France. We were supposed to go on Thursday and we cancelled everything [due to France's newly imposed travel restrictions] and decided to recreate sets in Florence, which is easy because Paris came out of Florence. I mean, so much that was designed here was taken to Paris, so it's not hard to find Paris in Florence.

One of the things that I really loved about your Beethoven show that was also livestreamed from Florence was the visuals. I found them so evocative and haunting.

That's what we're doing this time, too, but in a much more Paris way.

seen here in a previous performance

(Photo by Christopher Ash)

How do you develop the visual imagery for each show? I feel like what you're putting out there is so different and so much more sophisticated than anything else I'm seeing in these kinds of virtual presentations.

Thank you for that. I've been working on that and I kind of take pride in the fact we do that. It emerges from my imagination, if you want the honest truth. But my stage design has always been like that. I really just allow the story to evoke something and then it strikes me how to tell the story. And it's always Romance. I don't like putting things on a stage - you know there's a place for it, and I think it's important - but I don't like going to the theater and finding so much stuff on the stage that it looks like real life. That distresses me. I want to be allowed to feel, allowed to have things evoked for me in the theater.

I don't want to see a room on a stage, you know? For instance, when you go into a room, you don't take notice of absolutely everything in the room even though you know you're in a room. You take notice of certain things that evoke where you are and feel like something for you, and you remember those things. Yes, there are people who remember every detail of a room, but it's the combination of the things in a room that evoke. I've always felt the Chanel rule of thumb with design. Put stuff together and start taking stuff away and you'll maybe have a design, you know? It's getting to the elements.

That's what we're going to do with Debussy also. It's a very different type of evocation because I'm using a lot of the lighting and imagery that Whistler used in his paintings that Debussy was in love with. I'm using that kind of world, and that requires a certain Romance and a trust you don't have to spell everything out and that audiences will get what you're conveying. I guess they do. I don't know... I try! [laughs]

And I feel like that allows each audience member to take something slightly different from it, too.

Yeah, and to put their own sense of imagination into it. I can only speak for my stuff, I don't want to speak for everybody's stuff because that's not fair and true, but I have to put out there what I think will spur the imagination rather than you know, everything. Let it be evocative.

The show is being directed by artist Stefano Decarli. How did that partnership come about, and how do the two of you work together?

Well, he's standing not too far setting up a scene [laughs] so - [yelling to Decarli in the background "Stefano, the interviewer wants to know how we met and how much trouble you cause me!"] Here, I'll put him on the phone, you can ask him.

[Decarli comes on the line.] Hello?

Hello, Stefano.

Hi, hi.

Hi, this is Jim Munson from from BroadwayWorld. How did your partnership with Hershey come about and how do the two of you work together?

Well, I started with the editing of the Berlin [show], and then we just grew more and more together and now our partnership is very close.

During the actual livestream are you actively engaged in the production?

Yes, it's a very complex kind of work. It requires a lot of attention and a lot of focus. Everything comes together at once.

It's been nice chatting with you briefly. [laughs] Best of luck with A Paris Love Story.

Thank you very much. I will pass you back to Hershey. Bye bye.

[Felder comes back on the line.] My Italians are very sweet. [laughs]

How did you originally meet Stefano?

He came to me through a fixer. Here in Europe, particularly in London, you call people who put together film productions "fixers." I don't know what the equivalent is in America. I think you call it an executive producer or a line producer, maybe? I had a fixer in Britain who had made pictures here in Florence - this was for the Berlin [show], all the way back in May - I said, "We're coming out of lockdown. I need to find a group here who can do this." And I was put together with a group, Stefano was among them and he turned out to be quite a genius.

Each show is different and we were able to really join on the same wavelength of vision and how to take theater, keep it live, and yet do all these cinematic things at the same time. One of the things about Stefano is he has the technical know-how to do it, so it's not just a matter of thinking "Oh, we're going to do this." He actually knows how to execute this stuff, and so when we get the team together it's really kind of fun. Everybody's masked; I'm the only one in the whole operation who stays quarantined and has no mask.

Since you choose to do these shows as livestreams, I was wondering what the experience is like for you as a performer. I mean, there you are, probably at some ridiculously early hour in Florence, performing for an audience of people all over the world. Do you find that at all nerve-racking?

The whole thing is nerve-wracking, but what's nerve-wracking is not what anyone thinks until you do it. Now that I'm on my fourth one, what's unbearable is that you're not in control of technical things that happen in the ether. You know, when you're sitting in a hall with an audience and somebody falls asleep, somebody keels over, whatever it is, they're there and you can deal with them. In this, you have no control over somebody's wifi, you have no control over somebody's computer, so there's always hysteria. Audiences who love theater tend to be not as computer-savvy, you know, or their computers were bought to speak with grandchildren and children and they've been using the same thing for years, and our new system doesn't quite jive with their old one. It's all that kind of stuff.

When you sell a ticket, you want to make sure the product is both accessible and workable for everybody. You don't want to sell a ticket under the premise that they're not gonna be able to watch. Whereas when you're in the theater, you're playing the show and what you're seeing is what you're getting. If you have a technical problem in a theater, as long as there's one light on the stage and the piano plays, I can do the show, you know? All the other special effects don't matter. Here, there's technical things that never come into play in a theater, so it's just a constant stomachache. Is the broadcast going right, is it actually going out? You have no idea what's going on or not. So it's less the performance that's nerve-racking than all the other stuff that can really, literally send your stomach through a loop.

I can't imagine what it's like as an actor to perform into the ether. There's no way to read the room.

It's not that bad. You get used to the camera. I don't know how other actors do it, but I just take the lens as one person I'm talking to. And that's one person times 10,000, but it's one person so I'm talking directly to you, whoever you are. And, if you're comfortable doing that, and I am for whatever reason, it works. And you can give much more nuance by doing that because you don't have to speak out to a theater. Grand gestures can be tiny little intimate gestures as if you're talking to a friend. So that is the fun part. The rotten part is everything else! [laughs]

seen here in a previous performance

(Photo by Christopher Ash)

As a pianist, you have such a wide-ranging repertoire. What do you particularly love about playing Debussy's music?

First of all it's the music itself, the invention there, the mystical sense of how he created this stuff. I mean, how did he hear this stuff? To me it's so obvious - yes, that's what the ocean sounds like; yes that's what it sounds like if a faun wakes up in the afternoon and he's been dreaming about fairies [laughs]; yes that's what fireworks sound like; yes that's what the clair de lune sounds and feels like. But how did he hear that? Nobody before him heard like this. Nobody!

He broke the rules and somehow made music liquid. Yes, you can find liquidity in Chopin (and Debussy said, "Without Chopin, there'd be no Debussy."), but it's more than that. It's... notes are no longer notes. He's not bound to a musical language that everyone was bound to before him. And yet he uses the same notes, he doesn't use quarter tones and weird instruments, you know? How he managed to do it is simply beyond me. I've often said you can track the growth of composition through every single composer, you can see how Beethoven got to Bach, this one got to that one, and so forth. What you cannot see is where Debussy came from. You see that he took from here a little bit and from there a little bit, but he is never specifically the heir to something

I find it natural to play Debussy. It's easy. Not easy in the sense that just, oh, I throw it off. It's an easy like it feels natural, I know what to do with it, and I understand the colors. I've always been prone to colorism in instruments, and not just playing notes and so on and so forth. To me there is something about Debussy that is so evocative and colorful and magical that every time it's a discovery. It's not something you just play and play and this is the way it is. And if the scene goes a little bit differently, the music comes out differently. It's very odd. I know no other composer who allows you that kind of invention yet is strictly classical in his structure.

What about Debussy the man? What aspect of his character do you identify with the most closely?

Oh, practically nothing! [laughs] He was awful, he was complicated, but somehow in his music, he became very kind and very generous, so that part makes sense to me.

What is the Covid situation like in Italy right now? As you probably know, here in the U.S. we're in the midst of a horrendous sort of third wave, and yet we still have violent pushback in some quarters over even the simplest of safety measures.

People are dying, it's very serious and why it's not being taken as seriously in certain quarters in America, I don't know, but it's a lot of magical thinking, a lot of "Oh, it's not here so therefore it doesn't exist." Tomorrow [election day in the U.S.] is going to be a very important day, and it will define America's place in the world for a very long time, I think. And oddly it's less about who wins, but for me what's going to define who and what America is, is how whatever happens tomorrow is dealt with.

Italy is top-to-bottom different. In Florence we had a demonstration that was violent, but it was a different kind of violence. It was restaurateurs and tax drivers expressing anger at the police force, of being controlled that they can't make a living. But it was clear what it was about. It wasn't about just breaking windows, and it goes to show just how much Florentines love their city. They'll scream, they'll raise fists at each other, but they're not going to destroy their beautiful city. And that's so much of what makes this place so wonderful. But there is anger because, let's face it, what are people going to do when they can't eat? We're talking now not about people living in poverty, we're talking now about starvation, and so how is that going to work? It's very, very, very frightening.

On my end, I'm just doing a little bit to raise funds for, how shall I say, my gang, which is theaters and actors, because it's necessary. What are artists gonna do? There's no work. Nothing! Everybody was so gung-ho in London and I just got a mailing (The Stage) talking about the blow because Boris Johnson has to close down the country. Well, there's a serious pandemic and people are sick. What did anybody think was gonna happen? Why did anybody think that opening theaters and putting people together was a good idea? It wasn't. And I'm afraid that band-aiding this stuff, saying "OK, we're gonna do this just for now" is not right. We need to think about how we can get through this until the end, until this is gonna be OK.

Videos