Interview: Hai-Ting Chinn of SCIENCE FAIR: AN OPERA WITH EXPERIMENTS on MarshStream Celebrates Our Collective Capacity for Awe and Wonder

The Marsh presents the opera singer's boundary-breaking love letter to science on March 6th

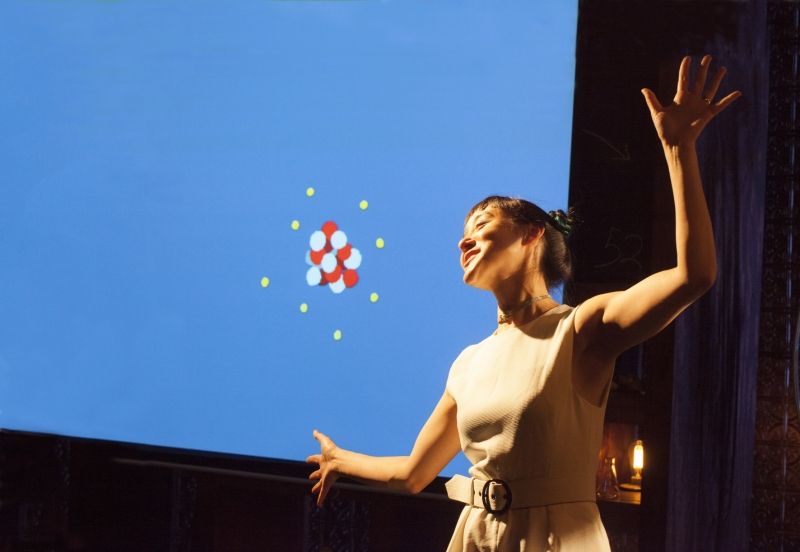

There are just some people on this planet who naturally operate on a more creative level than the rest of us, and mezzo-soprano Hai-Ting Chinn is clearly one of those people. She is bringing her wildly inventive musical science show Science Fair: An Opera with Experiments to The Marsh on Saturday, March 6th. Conceived and performed by Chinn with pianist Erika Switzer, Science Fair pairs luscious operatic vocals with light-hearted humor and science lectures. Chinn herself describes it as "a classical cabaret of science songs with science communication staging, including live experiments and slide shows, a little audience participation and a general sort of Bill Nye fun." Science Fair will be available for livestream at 5:00pm PST on March 6th, followed by a post-performance Q&A with The Marsh Founder/Artistic Director Stephanie Weisman. Chinn will also appear two days prior to that on Stephanie's MarshStream at 7:30pm on Thursday, March 4th to discuss this innovative work. For more information, visit www.themarsh.org/marshstream.

I had the pleasure of talking to Chinn last week from her home in the Hudson Valley, where she had just moved from New York City only two days earlier. A Northern California native with degrees from the Eastman and Yale Schools of Music, Shinn has enjoyed an unusually eclectic career, with credits as varied as touring around the world in Phillip Glass's Einstein on the Beach, playing Lady Thiang in The King and I on the West End, and performing with the experimental Wooster Group in New York. Given her resume, I had thought she might be fascinating to talk to, and she did not disappoint. I mean, what other opera singers do you know who do science in their spare time, just for fun? We talked about how Science Fair came to be, her passion for the creative process, and our evolving understanding around issues of racial and gender equity. In conversation, she is candid and accessible, brainy and funny, and always very, very thoughtful. Underlying everything is her enduring joy in pushing the boundaries of what it means to make musical art. The following conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Science Fair is quite a unique theater piece. What was your original impetus to create it?

Well, when I was growing up my mother was a Mathematics professor at Humboldt State University, and part of her career was working on what we now call "girls in STEM," but at the time was much less in the popular consciousness. She had various projects encouraging girls and women to go into the STEM fields and it was always a source of fun and interest for me. Eventually I became a professional musician and started following science as a hobby, so kind of the opposite of what most scientists do. I got so much joy out of new discoveries and reading about various fields and science communication that was happening when I was my 20's and 30's.

And at the same time, the classical music world is so ... let's just say there is a lot of religious music of various kinds that we are asked to do. We are asked to celebrate the feeling of wonder and awe that is often the domain of religion. For me, I was feeling that same kind of wonder through the scientific world view, and there was very little music celebrating that in the same way. I found myself at a point in my career where I kind of had a free year and I had this idea for making songs out of scientific lessons and texts. I had a few composers who I had worked with, including Stefan Weissman, Renée Favand-See and my husband Matthew Schickele, and had already at certain points asked them to write songs on non-poetic texts. For instance, one of the first ones was Stefan Weissman, who went to grad school with me, he set the ingredients of the Hostess Twinkie [laughs] and it was a big hit. It was actually on The Wendy Williams Show a few years back, when Hostess was going out of business.

Right! I remember that making a splash, especially for people like me who grew up loving Twinkies, but still find the ingredients a little frightening.

Yeah, absolutely! And it was kind of inspirational for how these complicated words could turn into really fun librettos. So I took those things, the desire to have music that inspired wonder about the scientific world view, the fun of setting non-traditional texts to classical music, and then the kind of fun that science communication was to me when I was growing up, in kind of the Tom Lehrer model of madcap science songs, and I just sort of threw those all together and came up with this idea. There's a small theater in downtown New York called HERE Arts Center, and they have a residency program for mid-career artists who want to try something experimental and new. They supported and produced the show and I developed it over a couple of years, commissioned 4 composers, created staging with a director, and slideshows with a comic artist, and that was it. That's how Science Fair was born.

Also, there was an element of giving back to the scientific community and celebrating what they do in an emotional and artistic way, because that's often how we celebrate great human achievements. I think the work being done by teachers and science communicators and podcasters and Youtubers, and all this culture of science communication is so fantastic and deserves to be celebrated. Scientific ways of thinking have improved human life in countless ways, even though often popular culture dwells on the negative effects and ignores all the ridiculous [amount of] positive change in the human condition that has been made by thinking scientifically. So I wanted to celebrate it and give something back.

I've always been fascinated that so many top scientists are also really good musicians. What do you think is behind the connection between science and music?

I know a lot of people remark on that, and some people say music is like math in that there's method, but I'm not sure we have a great scientific answer to that. It's obvious that the phenomenon is there in the world, that a lot of human beings who are interested in thinking scientifically are also very interested in thinking musically and making music. There's all kinds of theories, but I don't know that we have a firm answer.

You have such an eclectic performance history, everything from Baroque opera to Phillip Glass to Rodgers & Hammerstein to the Wooster Group. As a performer, do you approach those as very different things, or do you see them as more of a continuum?

Well, obviously for me it's a continuum, because whatever I'm hired to do it's always me you're hiring. I kind of made my career by never saying no to anything and also just being really game for whatever craziness a director or a composer wanted, and that's a double-edged sword. But it means more often than not that I end up being part of the creation of things, in one way or another, and that I definitely love. Maybe the continuum is that I always want to be part of the creation.

It doesn't necessarily serve me well when I'm doing something like a second-tier production of The King and I, which as a half-Asian performer, I had to do a lot when I was younger, because that's like so rote and set. I mean, being in the second or third cast, I was literally filling someone else's shoes and having to recreate exactly someone else's movements and actions. In situations like that, and also working in more traditional opera, I really have had mental and artistic problems, because I just can't bear not to give my artistic opinion. Which is just not always welcome. [laughs] And obviously it's only my opinion, and there's no right or wrong about it. I have definitely been wrong about many things.

Another thing that I love about science is the joy of being wrong. The whole point is that you want to learn more by being wrong and by admitting that you're wrong. I feel that's something that's really been a negative force in the world for the last four years especially, the idea that admitting you're wrong or you made a mistake is somehow not a good thing. Deliberately changing your mind when you get new information, that's like the vital force behind scientific advancement.

And obviously if you're going to approach your work in an experimental fashion, you're going to be wrong more often than you're right. That's the way progress is made.

Yeah, exactly, and you're trying to figure out how you're wrong. So anyway, I love being part of the creation of things. I'm opinionated and I like to share my artistic opinions - so that means that I often fit better into new or experimental projects, like the Wooster Group, which was the most amazing gig ever.

What was particularly amazing about working with the Wooster Group?

That was like kindergarten for grown artists. It was like a giant playpen. Everything that we made, it was like "everyone bring everything you've got and then we're gonna bring in some experts in various things to try to teach you like Period Baroque Gesture and then like TV acting." Everybody, the actors and the singers and the instrumentalists are all doing everything together, and everyone is bringing all their ideas, mashing them up, playing around, and then we would sit on the sidelines and say "Ooh, that was great! Keep that, do that again." It was like building a giant Lego castle out of a Baroque opera. It was just amazing - arduous, but amazing! [laughs]

And I imagine you have to be pretty fearless to work that way.

Yeah. I mean, collaborative theatre is definitely a way of working that, especially opera singers but I think also Broadway singers, are really not used to that kind of risk, like putting out there wholeheartedly what you've got, even if it's crazy and even though most of the time it's gonna be rejected. The things that I learned from those actors just sort of daring to do things full on, something that's off the top of their head, and then that might become part of the show...

And I suppose the flip side of that is if your "great idea" doesn't become part of the show to you have to be willing to just let go of it.

Yeah. Because like in science, nine times out of ten, it's rejected. [laughs]

I wanted to circle back to The King and I. You played Lady Thiang in London. When was that?

I played Tuptim on a second-string national tour in the U.S. in 1998, and then in 2001 I did Lady Thiang on the West End.

Lady Thiang has what I think is one of the best songs Rodgers & Hammerstein ever wrote - "Something Wonderful." But she's also a tricky character to pull off - like is she just an apologist for the King's worst behavior, and how do you avoid the sort of underlying Orientalism that is arguably baked into the show? How did you approach the character? How did you navigate those waters?

You know, honestly, I didn't. [pauses] That show is so complicated for an Asian actor. But when you're 26 years old and you get hired to do something on the West End, you just say "yes." And I've actually been thinking about that so much in these last couple of years because of the advancements we've all made in our thinking about race and gender. Because as you mentioned, Lady Thiang is probably one of the most problematic gender roles there is in Rodgers and Hammerstein, and yeah, I've been thinking about how as racialized actors, we're often forced by financial and career circumstances to perpetuate the stereotypes about our own heritage. We actually continue to build up these stereotypes because of the financial and career pressures in the arts, and it's a really weird line to walk. And you know in the late 90's, we didn't think about that quite as much. But I don't know what I would do if I were offered another Lady Thiang today, I genuinely don't.

And at the same time, I will admit I have a lot of affection for The King and I because I think there's a real heart to it. Do you think it's possible to do a production of the show that isn't problematic?

[pauses] Long silence! [laughs]

I realize I may be asking you a tough question here.

Yeah, the only way that I can imagine it not being problematic in 2021 is to like make it about aliens or something. As long as we are dealing with historical figures and people of different quote-unquote races - because as science shows us, race is a completely cultural construct anyway - we just haven't come to a place where it's not problematic. And I really like what you say about it being a show with a heart, because I feel like Rodgers and Hammerstein, you can say that about so many of their shows, that they were actually very progressive for their day. But that shows how far we've come that now their progressivism is incredibly problematic and racist and misogynistic and classist and all kinds of things. But nonetheless, you have to give them credit for being really brave and progressive in their day. Their day is just not ours.

And I believe that if Hammerstein in particular were alive today and writing something like The King and I, he would write a very different show. His impulses were largely right on, but he was also a man of his time.

Yeah. But who isn't? Like what are we doing now that in 50 years we're going to find incredibly regressive? And I mean, I actually think about this all the time, too - What is it that in 30 years that I'm going to be saying, "Oh, that's going too far! I just can't!"? What is it that is going to be that for our generation? I'm thinking of the gender pronoun thing. I know so many progressive people who just went through this gut reaction where they had all kinds of rationalizations for not wanting to use "they" - because it's grammatically incorrect, and they just can't think of a singular person like that. Which is just an absolute rationalization for your feeling of discomfort, that you don't want to change. And yet it's perceived by the next generation as a kind of prejudice.

And then we think about how our parents had a lot of trouble with certain racial things, even if they were progressive, good-hearted people. They had trouble letting go of ethnic jokes, or certain words that they didn't consider derogatory - that turned out to be really derogatory. Yeah, so I wonder about that in terms of the theatre. Like what is gonna hold up and manage to be reframed in a way that the art can be enjoyed?

Yeah, and I wonder what we as well-meaning folks trying to make the world a better place, what are we still getting just plain wrong?

Oh, yeah, yeah! Yep!

Not that I'm expecting you to have an answer to that! [laughs]

[laughs] Well, that kind of comes back to science, too. Because we have seen such a progression in various scientific fields in our lives. Think about the things we absolutely took for granted, and that have been completely overturned. And some people are great with that, and some people are not. The small ones like Pluto and the brontosaurus are great examples of people who will just fight something for no good reason, just because they learned something when they were a kid, and they can't let go of the idea that they were taught something that's now wrong.

The opera world is pretty tradition-bound, but it seems to me it is still more open to casting Asian performers in roles that weren't written specifically for Asians than say film, TV or Broadway are. Do you think there's any truth to that or am I way off the mark?

No, I think that's true. I think that, similar to Shakespeare in the theatre, with opera maybe it's just because it's old enough that many of the characters we don't recognize as current types so we're more willing to just cast [people of any race]. Like a courtesan. No one knows a courtesan anymore! There probably are some people that live that way, but no one has to be a courtesan because our society's just not structured like that, so no one has an idea what color a courtesan is. But then there are some [roles] that are recognizable, and obviously the most problematic ones are like Othello and Aida and Turandot.

And then you run into the really sticky situation of do you have to cast somebody who's the race that the 19th-century or 18th-century composer and librettist were imagining? Basically, at the moment the answer is "yes," but only because ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the opera world, and it's incredibly offensive to put on black or yellow face, and also racist to just continue hiring all white people. They are willing to kind of do multi-racial casting, but when it comes to the racialized roles, there's still a huge controversy that is evidenced in the fact that they're thinking about the race of the racialized characters and not about the race of the others. Do you see what I mean? I was not very coherent...

Yes, I do see your point, but it's really hard to talk about this stuff -

It really is!

- in a way that is understandable to everyone, because we all have our own language around it and our own experiences and our own biases. But getting back to my question, it seems to me as stodgy as opera can be, operas I've seen often have a more diverse cast, even in principal and secondary roles, than I would normally see in other art forms.

Yeah... maybe. It's hard for me to say because I don't spend a lot of time in traditional opera and I feel a little unqualified to comment.

If I go to see, say, La Traviata and Violetta happens to be played by a Chinese soprano, I don't think a thing about it. It feels like standard practice.

I think you're right, but at the same time, I know that I myself have run into trouble with people saying, "Ooh, I'm not sure I can cast an Asian this or that." And I know even more from speaking to Black singers that they run into incredible buried - and sometimes not so buried - racism in the opera world. And that's why I went on the tangent about racialized roles. Because if the opera world were truly egalitarian, then it wouldn't even be an issue who was playing Othello, because everyone would have equal opportunity and Iago could be Black. But can Iago be Black? No. Why not? Because we're not a post-racial society. And because there still is incredible prejudice against singers of color. And I know I don't experience it in the same way as Black Americans do, I have to say.

And I didn't mean to imply that you don't still experience some prejudice in opera.

It's been a long time since I was really in the opera world, and I've never really been in big houses. I mean New York City Opera is the biggest house that I was ever part of.

But that's not exactly a small house, you know?

Yeah, well, I mean... OK, here's an interesting story about City Opera, and I feel comfortable telling it because the whole management is gone. Less than a decade ago, I was cast in a show. I was the cover for the mainstage show, but then the covers performed outreach shows, for the kids to come in. We performed in the opera house, but it was for educational audiences. The mainstage cast - entirely white. The cover cast - rainbow. So they were doing the outreach, making sure to have ethnic faces, because the kids are gonna be kids of color from New York City. But the mainstage - well, we can still just cast it all white because - who cares? That's how it was.

I think it's safe to say that 2020 was a tough year for almost everyone, and we're all happy to leave it behind. What are you most looking forward to in 2021?

That's really easy! I am definitely looking forward to singing in spaces for live audiences. There's just nothing like singing, like making sound waves with other human beings in the same room and blending your sound waves together. I mean, it's why people sing in religion, and it brings us back to Science Fair. For some reason, it creates numinous feelings, feelings of wonder and awe and togetherness, and we have not gotten to do that for a year. And not only have we not gotten to do it, but singers have been branded super spreaders, so it felt like we're like pariahs, and engaging in that joyful activity has become literally life-threatening. So I am really looking forward to that no longer being a thing!

(All photos by Kate Milford)

Videos