Interview: Geoff Hoyle of WHAT WILL I BE WHEN YOU GROW UP? at The Marsh Lives to Play to Fool

The comedic legend explores his life's path and ponders his legacy in his latest work

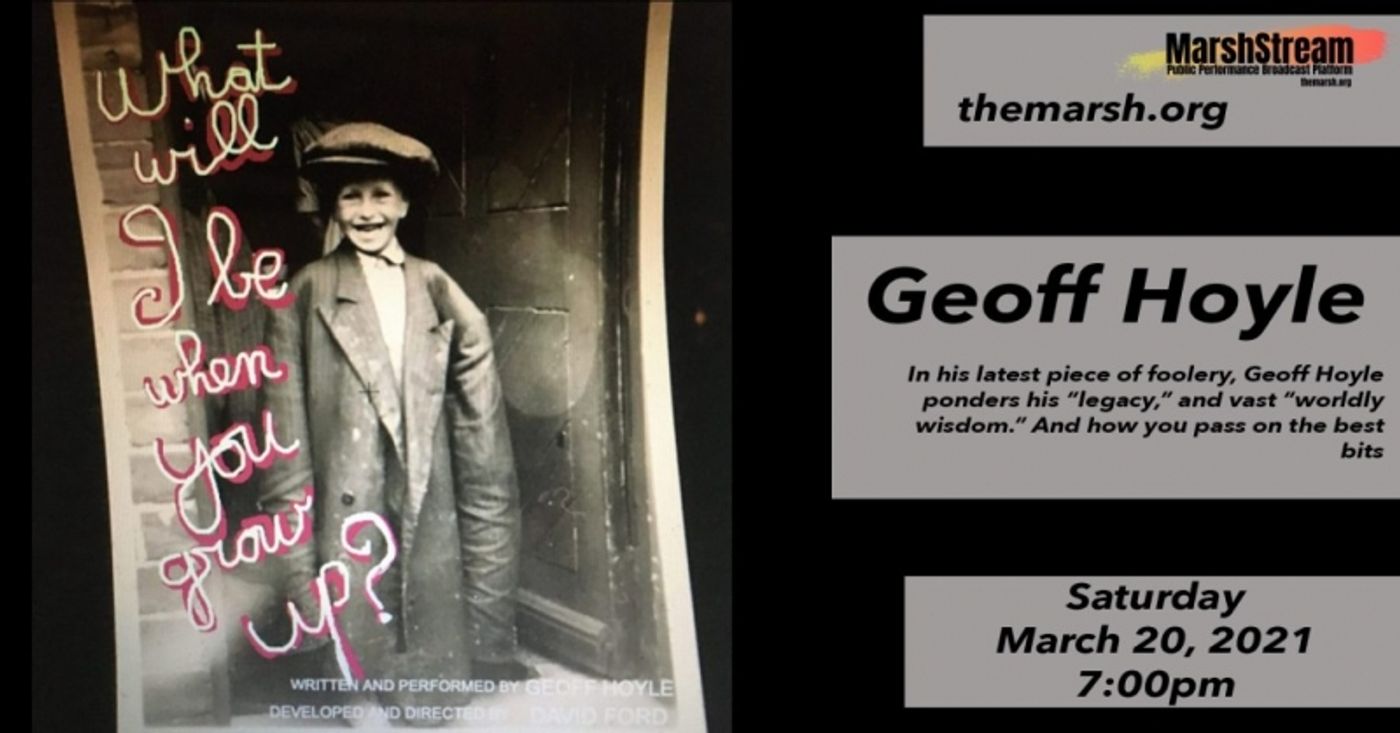

Ah, just when we need it the most, here is the perfect tonic for our troubled times! The Marsh is bringing back comedic legend Geoff Hoyle in his latest work, What Will I Be When You Grow Up? Available to watch on The Marsh's digital platform, MarshStream, for one-night-only, the filmed presentation will be presented on Saturday, March 20th at 7:00PM PDT. The show will be followed by a live post-performance Q&A with The Marsh Founder/Artistic Director Stephanie Weisman. Visit The Marsh website for more information.

Born and raised in England before coming to America in the 1970's, Hoyle has had a fascinating career and at this point has become a veritable Bay Area institution. After first coming to local attention as part of the Pickle Family Circus, he went on to perform with Cirque du Soleil, create the role of Zazu in the original Broadway company of The Lion King, act in plays at virtually all the major Bay Area theater companies, and create numerous solo shows, many of them at The Marsh.

I recently caught up with Hoyle by phone from his home in Inverness, California. It is immediately clear that he is a born entertainer, always ready with a joke in even the direst of circumstances. He sees himself as a sort of inveterate "fool" in the Shakespearean sense. He's the one who constantly pokes fun in the interest of exposing the truth. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

What prompted you to create What Will I Be When You Grow Up?

It's been over two years that David Ford and I have been batting around ideas and it didn't really crystallize until maybe the end of last year. I played around with an idea, originally called "What If?" Given that I've turned 74, and actually have almost ¾ of a century to look back on, "What If?" became a relevant question for me. What if I'd done this? What if I had done that? What if I had taken that road not taken? And why did I do certain things?" So it became an inquiry into how one makes decisions, if one makes decisions. And I'd become a grandfather almost five years ago, and the questions kept arising in my mind, "How would I tell them how I got to be where I am? What do you say to your grandchildren? What is your legacy? What is all your worldly wisdom? Is there any?" [laughs]

The other thing that happened is I'm spending time playing with my grandchildren. I have one in Paris, one in Oakland, and two [more] on the way. I had a teacher once, Geoffrey Reeves, who wrote a book about Peter Brook. Then he stopped doing work, and I couldn't figure out why. People would say, "What happened to Jeffrey? Why isn't Jeffrey directing? It was always fun to work with him. Oh, he's just playing with his grandchildren." And I thought "Oh, that's too bad. We've lost someone else in the world of the thee-a-tuh." And now I get it. I call grandchildren the 'new now' because they're more important, more vibrant than anything else in many ways. They take you out of the worst of what we're experiencing now, or could experience, or have experienced. The somehow psychic-spiritual-natural thing that happens when you have grandchildren is you get to relive your children's lives once removed. All the joy and none of the hassle. [laughs] Fill 'em full of ice cream and give 'em back, is the joke.

Suddenly we're hit with Covid and you can't be with your grandchildren anymore, and that is the opening of the show. I'm on FaceTime or some app with my grandchild and he has to go. His dad calls him, and he rings off and I'm bereft because I can't be with him because of Covid. The urgency of being with him and telling him how to make a bow and arrow, or how to be safe around matches, or reading a story about a giant, that urgency becomes much more urgent.

I think many people will identify with not being with their loved ones, or at least being very careful about how many germs have they had that they're gonna give you because you're now in a risk cohort. So it's a little fraught and anxious, plus you've got the fraught political situation in the body politic and you've got the death of the planet looming. [laughs]

Yeah, there's that!

I'm sitting here in Inverness, California, hoping the fire doesn't burn my house down because we were on the evacuation warning, still are. That's [from] the lightning strikes that were part of an outcome from climate change, but there are people who don't actually believe it, and that adds to the political divide and the craziness of it all. Unfortunately, we have a lot of agency in the natural world, which we don't often use very smartly.

You worked with David Ford on this show and others. Everyone who's worked with David always says "Oh, he's great!" What do you think it is that makes him so successful at what he does?

He's very patient and good at finding a kernel of something that you need to explore further within your babble. He's very good at the jigsaw of your ramblings and putting them together in some kind of coherent piece. He's also very disciplined and rigorous. I call him David 'Don't-Need-It' Ford. "Do you think I should - What if I have this bit in here?" "Mmmm... don't need it." "But I'm not saying what I really mean, I'm not sure people are going to get it, I need this extra bit." "Don't need it." As Ray Bradbury said, the true artist knows what to leave out. But David's also quite patient and very forgiving so you feel safe when you go off into some mad stuff.

You were you born in England, correct?

Yeah, in Kingston-Upon-Hull. William Wilberforce lived there and was a member of Parliament and a big anti-slavery advocate, you know an agitator, so it's the home of certain progressive ideas. It's a pretty interesting town. It actually was named the Cultural Center of Europe for a year. It's seen a lot of ups and downs. It received the worst bombing by the Luftwaffe in the second world war outside of London. It was terribly, terribly bombed, and they're still finding unexploded bombs when they go into basements and tear up buildings up to rebuild.

I went to university in Birmingham. It's a depressed industrial heartland, basically rust bowl. It's awful! [laughs] But it had one of the first drama departments in a university in England so that's why I landed up there. I wanted to learn acting and that stuff. It's in this show actually, little bits of what I did at Birmingham, although I don't mention Birmingham. But the suburbs are nice, and it's close to Stratford so we could go there a lot to see shows.

How did you come to the States?

I met my wife in London, in a pub actually. I didn't know this, but she was about to come and work with the group that I was working with at the time. She had left [the U.S.] when the Weather Underground started bombing and were starting to get very militant. She didn't espouse the violent turn and the way that the Weather Underground had sort of hijacked the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society]. So she left and that's how she went to London and met me.

After about a couple of years, she decided she wanted to come back to America. She landed in America, I think, on the day after Roe vs. Wade was made law. Then I followed - cherchez la femme, you know. I also wanted to see America because I was intrigued and the group that I was with had sort of tentative plans to do some work in America. But I left before it did, so I had to do it on my own steam.

When you came to America, what sort of career did you imagine for yourself?

We didn't really imagine careers back then. I came over in 1973. Nixon was about to resign, and my wife was living on a hippie commune in the Ozark Mountains, so I went from London to Berryville, Arkansas.

Wow!

I took the bus up from Little Rock, and saw cotton balls growing in the field and said to the people on the bus, "What are those tin shacks? Is that where they store the cotton?" And they said, "No, that's where people live." And I thought "Oh...Oh, yes, that part of America." And, well, we've seen the fruits of all that now. It's what Biden was talking about, original sin, even yesterday in Kenosha.

So I went to this hippie commune in the Ozark Mountains, and we were growing marijuana and vegetables and goats and helping other local farmers, all of whom were white, the place was totally white. Berryville was where you went to the hardware store, but there was another place not too far away from the Missouri-Arkansas border called Eureka Springs (or "You-RIK-uh Shprings"), an old Victorian watering place that had gone to seed. It's now I think been completely gussied up and gentrified so that they've revived the spa. There was a place there called The Quiet Night and they put on cabarets and stuff, and people who were in the commune had a band and they played and entertained people. I did a show there one night and it went well. I was just playing around with stuff and improvising. In London I'd done a lot of street theater, with children mostly, and then worked with some experimental stuff, and worked with Stoppard. Tom Stoppard was kind of a friend of ours, of the group we worked in, and after I left there, I did some TV stuff and made enough money to get my airfare together to come here.

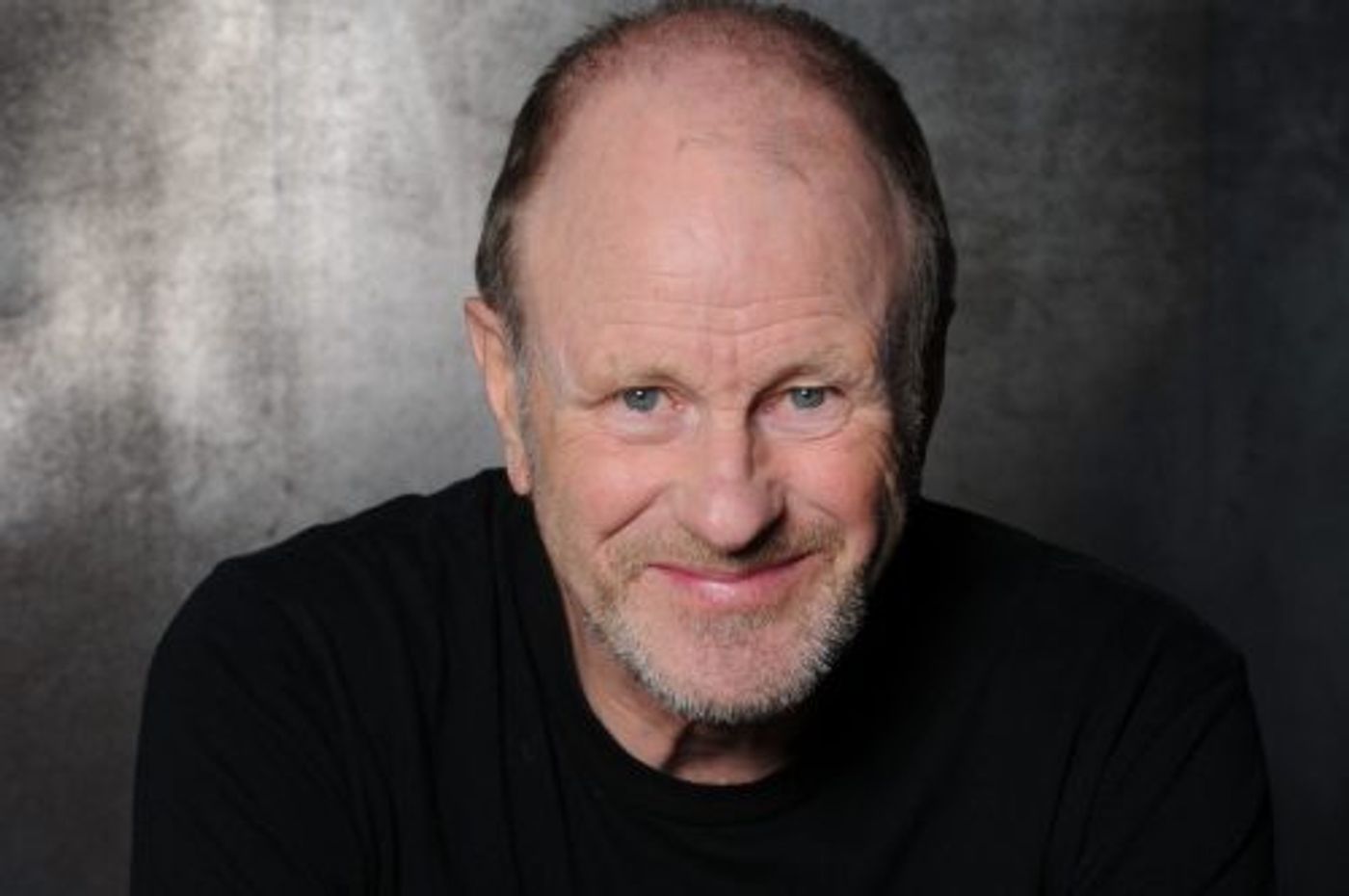

(Photo by Lisa Keating)

How did you make the leap from Arkansas to San Francisco?

One of the reasons that I came over [to America] is that Mary, my wife, had sent me this cutting from the Village Voice, which was a review of, I think it was "Dragon Lady's Revenge" that the San Francisco Mime Troupe were doing. They were using commedia masks and I'd studied commedia a little bit and I'd done two years of mime training in Paris, after I left Birmingham. I was really intrigued by these masked characters, outdoors, popular theater, political, progressive, and I said "That's the kind of stuff I'd like to do." So that was sort of in the back of our minds when we came to the West Coast. We hitchhiked out of Arkansas to San Francisco. Mary had some friends in San Francisco where we could kind of hook up.

When I got there, I went to the Mime Troupe. They were looking for a person of color who played a musical instrument and so I didn't fit the bill. And then I met somebody who happened to be in the street performing at the Grant Street Crafts Fair in North Beach. He had worked with me in London and he was fire eating and just passing the hat. He couldn't work [legally], he had no permit. He said "Why don't you come out?" We started a little group, and it was real catch-as-catch-can. At the end of about a year, we had bought a car and went to the International Mime Festival in La Crosse, Wisconsin at Viterbo College. It was nuts! It was 1974, we'd just basically pass the hat at city/town squares and campuses to work our way across the country to this mime thing which we weren't part of. We did our own stuff outside and sort of hijacked various performances and we had a good time.

How did you connect with Pickle Family Circus?

The guy who I'd met who was into fire eating said, "Gee, I'm gonna take you to see this circus." I said, "What?!" It was at Mission High School, I think. There was like a little circus, no animals, and there were these amazing jugglers. It turned out that was Larry Pisoni and Cecil MacKinnon and Peggy Snider, who were at the time the Pickle Family Jugglers. Larry and Peggy had worked at the Mime Troupe and then decided to spin off, cause Larry was very into circus, it was his total passion. So they started it up and got a 5-piece band, which played jazz music, very strange for a circus. And they had this other guy, Bill Irwin, who was Willie the Clown. I looked at him and saw him walk and I said, "This guy is not like other American clowns that I've seen. This guy really has a character, and he's not averse to being nasty [laughs] and going for a character that really had an agenda. That is very different."

Then the call came out that they wanted more people to work for this circus, and I auditioned for Larry. I did this crazy thing which I won't go into here, and he hired me on the spot. And so that's how I started working with the circus.

And you also went on to work with Cirque du Soleil

Yeah - that was much later.

Since you worked with both Pickle Family and Cirque du Soleil, I'm curious how would you compare the two circuses as someone who experienced them from the inside?

Well, they're very different. Initially, I think, the Cirque du Soleil had some similarities with Pickle Family Circus. They had no animals, it was basically human skill, they were somewhat rebellious, I mean their very first show was called "We Reinvent the Circus." I saw them and thought they were fantastic. They were using masks and this kind of interesting story that they wove through all the acts. And they initially, I think, were sort of non-profit and Pickle Family Circus was non-profit. And it came out of this kind of iconoclastic street performance ethic that they were trying to infuse into a circus aesthetic.

Pickle Family Circus had sort of a political agenda in that the shows were put on to raise money for service organizations. We would do shows presented by local service organizations, childcare centers, clinics, senior centers, alternate schools. We would raise money for them, because the normal circus, the Shriner's Circus, raises money for the Shriners Hospital and it goes to children's welfare, and now we were doing it for cooperative, collective organizations, and bookshops that were progressive. Cirque du Soleil never had that. You go into the Cirque du Soleil tent now and it says "Presented by AT&T" so it's a completely corporate entity and has made a lot of money. It is not a collective, it is not a cooperative, it's a total business hierarchy. As such, it's no surprise that it's paired off in many ways with Disney, which is involved in is what I find one of the most interesting oxymorons in the performing arts. They're involved in what is known as the "leisure industry." [laughs uproariously] Enough said. You know, money talks.

Which leads me to The Lion King. It's the only Broadway show on your resume, but it's a doozy! Given that you didn't come from a standard musical theater background, how did you get that job?

Well, it's completely connections, because I knew Julie Taymor. I think Julie was at Oberlin with Bill Irwin and Kimi Okada, one of the founder members of ODC San Francisco (ODC stands for Oberlin Dance Collective). I'm still incredibly supportive of ODC and I narrate The Velveteen Rabbit whenever they ask me to do it.

So - Julie was part of that group, and when I took some bits and pieces to Dance Theater Workshop in the early 90's, she came and saw me and we talked, and Bill and Kimi and Oberlin came up. She had a show that she was doing called The Measures Taken, I believe, and it had incredible masks that she had made. She's an amazing mask-maker, not just animal masks like The Lion King which she's internationally known for, but she has these caricature masks that are like Daumier, they're absolutely astonishing. She tried to get me involved in that show and I probably should have done it, but she was on the East coast and I was on the West coast, so that was problematical.

But [years later for The Lion King], she asked me to come in and audition for the [Disney] suits. So I went to New York and auditioned and it was clear to them, I think that, she wanted me because of my mimetic skills, and also I had puppetry skills. She had seen me do a show I'd put together of my own solos called The Fool Show. I did some puppetry in that and I think she thought, "Oh, wow, this guy knows how to do this and get maximum effect with minimum effort."

The Lion King quickly became such a cultural phenomenon that it's easy to forget that at the time it was considered a somewhat risky proposition. When you think back to the rehearsal period for that show, did you have any idea what a big deal it would become?

I didn't. Well, it had the backing of Disney Theatrical, and that was part of the Disney empire, so you knew that if they wanted to, they could throw money at it. They had already done Beauty and the Beast and had a couple of things they'd taken from their media empire and transferred to live performance. And I think they had so much money to play with so that they could get an internationally renowned cast of people. Elton John (I don't know how much he got paid!) [laughs], and Tim Rice, who wrote me that song, "The Morning Report" (Ugh, let's not go there!). And Lebo M who was the African singer and musician and percussionist, amazing guy, plus all these people from South Africa. Paul Simon had used Ladysmith Black Mambazo and that had started to sort of percolate, so I mean you can see it as a real cynical play by Disney to use an African-based story that would increase their audience potential.

But - it was wonderful. And it was hard.

What was the hard part for you?

It was very rigorous, very demanding work, and Disney were completely, in my estimation, unforgiving, in terms of what it meant [to the performers]. And to do that eight times a week, it was a punishing schedule. I think one holiday season we did at least 11, some insane number of shows, back to back. I would sleep in the shower between matinee and evening because the New Amsterdam was limited in its space. We felt just real pawns in some kind of bigger game. It was not very actor-centric. And as my friend, Clive Barker, an actor who was with Joan Littlewood in the 60's would say, the actor is the theater. You can do it without lights, costumes, sound, but you can't do theater without actors. And I didn't feel like we were particularly well-treated. I mean the money wasn't that great. It was OK, but they hard-balled it. Disney wouldn't give an inch, in terms of extra payment. They would only work within their production contract, which is separate from the standard Broadway production contract. It's similar, but they created their own. Because they could. I don't know... You've seen The Lion King?

Yes

Did you like it?

My honest answer is I 'kinda liked' it. I loved certain aspects of it, but watching how hard the performers were working onstage while hidden behind those cumbersome costumes, I just kept thinking, "I bet this is not a fun show to perform."

You said it, not me! [laughs] Yeah, I mean we were completely buried. I had like an hour's makeup. I was blue from my hairline, which is getting thinner by the second [laughs], down to my chest, and then I had to get all that off every night. There was a guy who worked for Beauty and the Beast, and he sent us an opening night telegram. He said, "Lots and lots of love! And remember - it's all about the costumes!" [laughs]

And, OK, I made some money, but not much. I wouldn't say I walked away with a ton o' change. They didn't give us a Tony bump, in my memory. We won the Tony [for Best Musical]. I thought Ragtime was gonna get it, and I was standing at the back of the New Amsterdam Theatre, which is where they were projecting it [for the cast], because it was at Radio City Music Hall. Anyway, I was standing at the back of that house with John Vickery, who played Scar. We shared a dressing room and we were the old guys, 'those grumpy guys from Northern California.' [laughs]

And I remember when they announced it, John Vickery and I just looked at each other like deer in headlights, like "Are you kidding me?! The Lion King won?!" And all the younger dancers, who were all fantastic, unbelievable dancers, were jumping up and down and I felt like a spectator, I didn't feel like a co-worker.

We had times where there were so many injuries, because Garth Fagan's amazing choreography - and he's a wonderful choreographer, and a brilliant dancer and a really nice guy - it was so demanding that all the swings were in the lineup. There was no one left. There would be so many injuries. John Vickery told me a story. You see he's supposed to look down at the lionesses who are all out to get him, like 8 or 9 or 10 of 'em in the lionesses dance. He looks down and he's supposed to refer to "the pride, you in the pride." He looks down and there's just two left. And he says "You...two!" [laughs] Because they wouldn't hire enough swings and the choreography was too demanding.

I did 469 performances in the year I was there, and then they said, "Do you want to reup?" I said, "I'll give you 6 months." They said, "No, it has to be a year." and they offered me a little bit of a salary increase. I said "No, I got family, I got other things I need to do on the West Coast. OK, bye." John Vickery and I left at the same time, and we said to them [Disney], "We'd like to see the show. We've never seen it." So they got us some tickets, and I said,"OK, great. Thanks!" And they said, "They're $80 each." [pause] So, there ya go.

With everything going on the world right now, most people are struggling to some degree. I figure as a professional clown it's pretty much your job to find the humor in any situation. Where are you finding joy in the world these days?

Hah! Well - irony is the clown's weapon, or the fool's weapon, I will say. I consider myself more of a fool than a circus clown, but in the sort of Dario Fo kind of way, turning the beast over and saying "Look, there's nothing underneath." Ya know? Look underneath the bishop's clothes, and there's nothing, they're just the same as the rest of us. You're revealing the hypocrisies and the ironies of what people say and what they do, particularly with politicians. Look, irony with politics right now has sort of reached... you can't write it that weird! It's really terrifying.

I find humor in everyday things like how to wear a mask. One of the things I do in this show, since it's on Zoom, when I enter, I'm wearing a mask. You can't hear anything I'm saying, so it's "Oh, wait, I've got to take this off now. I can't infect you. You're on the other side of the screen." I play around with those things and the fact the technology is so advanced and so pathetic at the same time. [laughs] I do imitations of frozen Zoom screens. You know, technology is so overrated and somebody has to cry wolf, somebody has to say the emperor has no clothes.

What we have is ourselves, in the presence of each other, and our kindness. I don't want to say we have to be sappy with each other, but we do have to be kind, and we do have to call it when the emperor comes on and he has no clothes, be it technology, reportage, politics, claims, the can-do of America, you know? It's a young country. In Europe, we've had plagues, we know what this is.

Videos