Interview: Doug Varone of DOUG VARONE AND DANCERS at The Hammer Theatre Center Offers a Whole New Way to Experience the Iconic Score to 'West Side Story'

Varone's award-winning dance company will perform "Somewhere" on its program in San Jose on October 29th and 30th

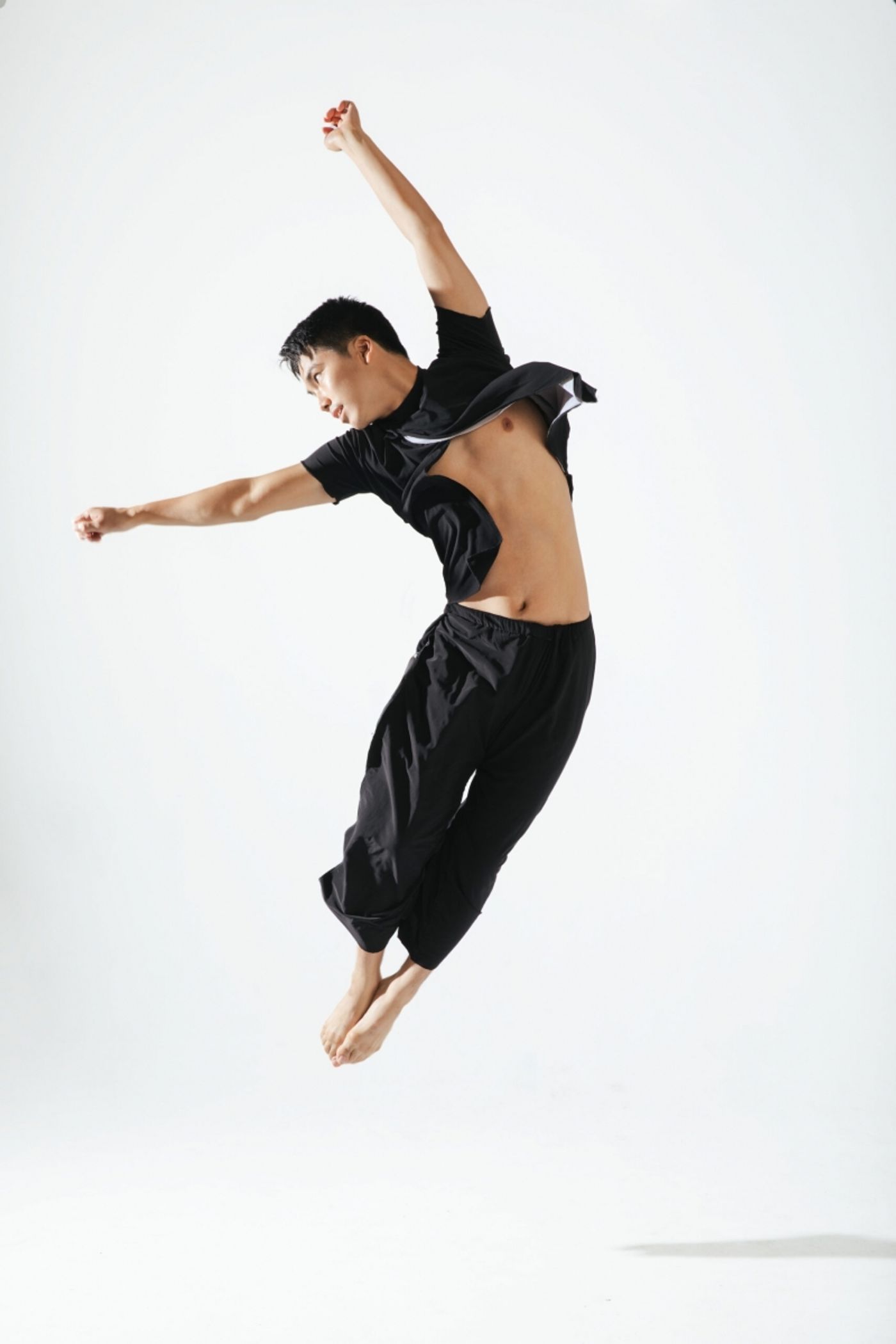

(photo by David Bazemore)

Doug Varone and Dancers are making a much-anticipated return to San Jose with a program featuring Somewhere, a non-narrative work set to the orchestral score from West Side Story. Varone has created a pure-movement-based dance that allows the audience to experience Leonard Bernstein's iconic music in a whole new way, and it has been wowing audiences since its premiere in 2019. Also on the program are two dances set to the music of Philip Glass - the exuberant Lux, which has become the company's signature piece, and Octet, a brand-new work incorporating dancers from the San Jose University Dance Department. The program will be performed live at the Hammer Theatre Center in San Jose on Friday October 29th and Saturday October 30th. In accordance with current COVID protocols, audience members will be required to provide proof of vaccination and remain masked throughout the performance. For tickets and additional information, visit hammertheatre.com.

Varone has enjoyed a long and multi-faceted career that shows no signs of letting up. In addition to leading his own 11-time Bessie-Award-winning dance company for over 30 years (as if that weren't enough!), he has also choreographed for other top dance companies such as Paul Taylor and Martha Graham, directed and choreographed at the Metropolitan Opera, and serves on the faculty of Purchase College in New York. His theater credits include choreographing two musicals that have become cult favorites, Triumph of Love on Broadway and Murder Ballad Off-Broadway. He also received an Obie Award for directing and choreographing the Lincoln Center production of Ricky Ian Gordon's Orpheus and Euridice.

I had the pleasure of catching up with Varone last week from his home base in New York City. A self-described musical theater geek, Varone is one of those creative individuals who just naturally seems to eat, sleep and breathe dance, music and theater. Known for crafting movement that appears to be spontaneous even though it is carefully choreographed, I was fascinated to learn that he sees his signature style as a sort of natural extension of the dancing of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly in classic MGM musicals. We also talked about how he came up with the notion to divorce the score of West Side Story from any suggestion of a plot, how his company has managed to survive the pandemic intact, and what it was like working on and off Broadway. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What has life been like since March of 2020? How has your company managed to survive?

Well, it's been a challenge for sure. I mean we literally were getting ready to go on tour on March 13th 2020, and March 12th is when everything closed down. So I sent the dancers home thinking it would be a short 2 or 3-week respite, and 18 months later here we are. About 2 weeks ago, we went back into rehearsal for the first time live together since that day.

In the course of that year, we were able to continue creating. I created a series of short films that we presented remotely, which was really fascinating. I had done some film work earlier on in my career, and this kind of gave me the opportunity to go back to that process and that love. We also were able to build up our educational component in a new way by teaching virtually across the country at universities and colleges, building kind of a virtual presence within those communities. So those things helped us stay on track.

For me, of course, the disappointing aspect of it all was trying to stay connected with the dancers through Zoom. We had a company meeting every day with my staff. We all sort of left New York so our office was abandoned, and we worked remotely. We kept the fires burning, and financially we were able to keep ourselves afloat and happily are in an OK place to start finding our way back to live performances and live creativity. The thing I missed the most was being in the studio with artists that I care about, artists that I trust within the creative process, and continuing that process with them.

And of course, the year was fraught with so much going on in the world, not just COVID. To not have a creative outlet to share a voice about that was frustrating, but also it gave myself as an artist time to breathe. When you run a dance company for so many years, you're constantly moving and trying to regenerate and find new reasons for survival. The silver lining was it gave us the opportunity to look deep into the organization and find a way to reinvent ourselves as we are coming back.

The San Jose program includes Somewhere, which I'm particularly excited about. It's set to music that I love and know so well, and I think so many of us have our own associations with the original Jerome Robbins' choreography -

Absolutely!

- so how did you approach creating your own take on such iconic dance music?

The genesis of it was that we were actually creating a different, pure-movement work and one night after rehearsal I turned on TCM and there was West Side Story. I grew up with it, you know I'm a theater geek, and I thought to myself "Gosh, this music is so extraordinary. I'm curious what it would be like if the narrative was stripped away and it was just pure movement." You know, the same way many story ballets are done. There are movement-based versions of Firebird and Rite of Spring, things that are iconic in their own way, right?

So I went into rehearsal the next day and put the music to the Prologue on and said, "Let's just see the dance that we're creating now to this." And something just synched up. It was this beautiful juxtaposition between pure movement against this score that I knew so well. I felt like I knew every finger snap, I can tell you exactly where they are in the film. And I thought to myself "This could be pretty extraordinary." So we began the process of using the orchestrations to West Side Story, several different versions, and creating what I would call a pure-movement-based, non-narrative work to this iconic score. No Tony, no Maria, no Jets, no Bernardo - none of that. Just responding the way I would to any score that I'm creating to, and seeing if it was possible to get rid of my preconceived ideas of what the score was and find a new approach to it.

It's the first time that the Bernstein Foundation granted the rights to a choreographer to create to that score, void of a West Side Story production. They were hesitant, but we really delivered for them, and they're thrilled with the work. And it was a fantastic process. I have a company of dancers, many of whom were steeped in the score itself and knew it well, and others who surprisingly had never seen the movie, didn't know the lyrics. So it was this interesting mix of people that were approaching it from a point of view where they needed to scrape away all that baggage, and then others that had no baggage to bring to it.

Whenever we show the work in live performance, I'm eager to talk to the audience afterwards to ask them how long it took them to get rid of their imagery. Like here's the Prologue, everyone knows what's happening, and all the sudden it's not happening up onstage. To my great surprise and delight people are completely along for the ride and begin to see and hear the music differently. Their brains are being kind of retooled to see something else to it.

That's really interesting to me. I mean, if I go see a stage production of West Side Story, then yeah, I want to see the Jerome Robbins choreography. But the music is also so amazing in its own right that it really stands on its own -

It's incredible!

- So there's no reason it can't also be something else, you know?

Yes. And I think we've made that something else, so I am kind of thrilled with it.

(photo by Erin Baiano)

The San Jose program also includes two pieces set to the music of Philip Glass.

Yes. We are bringing a piece entitled Lux which was created in 2006. It's more or less become our hallmark piece and it's on pretty much every program that we create. It's an incredibly optimistic work, it's about the joy of moving. The score and the dancing together lift the roof a bit, and I can't think of any better piece to be bringing out on the road right now after the last year that we've had.

The other piece we are creating, Octet, is a project we're doing with the San Jose University Dance Department. Last year we staged a work on them remotely. I was in my house in upstate New York and they were in the studio. What we're going to do for this project is mix four company members with four of their students to recreate the piece. We're excited about sharing the stage with the students, and having them share the stage with us, as kind of an educational tool as well.

In an interview some years ago, you said you wanted your dances to "look like they're happening in the moment, rather than planned." How do you achieve that effect?

As I mentioned, I kind of grew up a musical theater geek. I was a young tap dancer and my icons were Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. I grew up watching MGM musicals, and I think that stayed with me. You know there's something so extraordinary about watching Fred Astaire just walk down the street and very slowly find his way into a rhythm and then something happens and there's a dance happening, and all of a sudden he's back into a scene. That magical sense of blurring the line between being a pedestrian and being a fantastic dance technician is something I strive for, not only as a dancer, but also within my choreography. The world feels as if there's a spontaneity to it. Even though the work is entirely choreographed, there is a sense that it's just happening in the moment up onstage.

That reminds me of the toy store scene at the beginning of Easter Parade where Fred Astaire casually encounters a variety of objects and works out a way to dance with each one. It really does look like he's making it up as he goes along.

Exactly. For me that was inspiring as a young kid, and I think it sub-consciously stayed within me. As I began to explore my own movement vocabulary, that was in the back of my head.

I really enjoy the fluidity of your movement, how it feels like one movement just naturally leads into the next without any break.

Thank you. I feel there should be something organic about it, and also I would say something non-performative about it. I direct the dancers to just be natural and to interface with each other in a way that allows the audience to be engaged, but not to be performing for the audience. For me that has also always been important. I'm not drawn to performative dance where you know dancers are onstage dancing for the audience. I feel as if I could close the fourth wall, I would do that.

You've also choreographed a couple of musicals in New York that have become sort of obsessions for musical theater geeks - Triumph of Love and Murder Ballad. Those two shows featured a sort of who's who of amazing performers like Betty Buckley, F. Murray Abraham, Roger Bart, Karen Olivo, Christopher Sieber, Caissie Levy, Rebecca Naomi Jones, Nancy Opel, Will Swensen and on and on. What was it like working on those two shows?

Well, they were at two completely different points in my career. Triumph started with regional productions at Yale and Center Stage in Baltimore, and then it moved to Broadway. It was fascinating to be part of the genesis of something, and then watch it grow and shift and change and morph into a larger production for the Broadway stage. And once again being a musical theater geek, it was fascinating to be at the Royale Theatre where I remembered seeing Grease, you know 40 years ago, right? To work with artists of that caliber and to be part of a team led by my friend Michael Mayer was an extraordinary time.

Murder Ballad was more recent and it was a smaller project, a cast of only four, but four extraordinary artists that were real collaborators in the process. In that regard the two shows were very, very different. With Triumph it was very much about choregraphing events for the show. With Murder Ballad, I really was collaborating with these artists on movement vocabulary, on musical staging, and in many ways it was much more familiar in terms of the way that I work with my own company.

Both musicals were so radically different in terms of what they were trying to achieve. Murder Ballad was very inclusive, it took place in a bar, literally with audience all around and we needed to keep that in mind as we were creating, like how do you stay true the story you're telling, but also engage the audience? Triumph on the other hand was a proscenium-based show and journey.

For Murder Ballad how did you design movement for such an intimate space where the actors were essentially performing in and amongst the audience?

It's really trial and error. I mean what we do is create to the set in the space, and the first preview you're learning something, like where the audience is really sitting, how are they looking, where are they looking, where do you want them to look? It begins to change your perception of what's important and how you need to restage something somewhere else because the audience can't view it all of the sudden. So the previews were really, really informative for that show. It was close quarters. When we first did it at Manhattan Theatre Club in the downstairs space, I don't think there were more than 90 people in the space. Then we moved it to an Off-Broadway theater for a short bit and it was far more spacious, but oddly I preferred the smaller theater. The intimacy of it, the claustrophobia of it, I thought worked beautifully for the show.

You mentioned that Michael Mayer is a friend of yours, and he's one of my favorite directors. How did you originally meet him?

I did a show with Michael at the Vineyard Theatre entitled America Dreaming. He was looking for a choreographer, and I was recommended by a friend of his, so we met in a coffee shop and I took on the project and that was it. That was very early on, pre-Triumph of Love, pre-everything that Michael's done. He's had a great, great body of work.

After over 3 decades as a dancemaker, what drives you to keep creating new work?

Well, that is a really good question! [laughs]

When you get up in the morning, what's that thing that makes you think "I need to make something new today"?

I still feel like I have things I want to be exploring. Every time I walk into a studio to create a work, I try to challenge myself to create something new and different. Whether I succeed, I don't know - and probably not - but I have to trick myself into getting into that studio saying "Hey, I've got this new idea."

I do feel as if the kind of works I'm interested in creating, and the scope that those might entail now that [the] COVID [shutdown] is over, will be far greater. I'm interested in creating larger projects that might not be tourable. I'd like to get back to creating and directing opera. I did a great deal of that and of course that all disappeared after COVID hit. So I'm looking at the larger picture of my career, not just the dancemaking. I feel like I'm in the "second-and-a-half act" of my life right now, and eager to see where that leads, you know before the third act begins.

Well, you've certainly had a fascinating career so far.

I feel really blessed about that. Every so often I kind of look back on all the things that I've done and I feel really grateful for the opportunities that I've had, for sure.

Videos