Interview: Director/Choreographer Martín Santangelo of ENTRE TU Y YO at Z Space Shares His Passion for Flamenco as a Dramatic Form

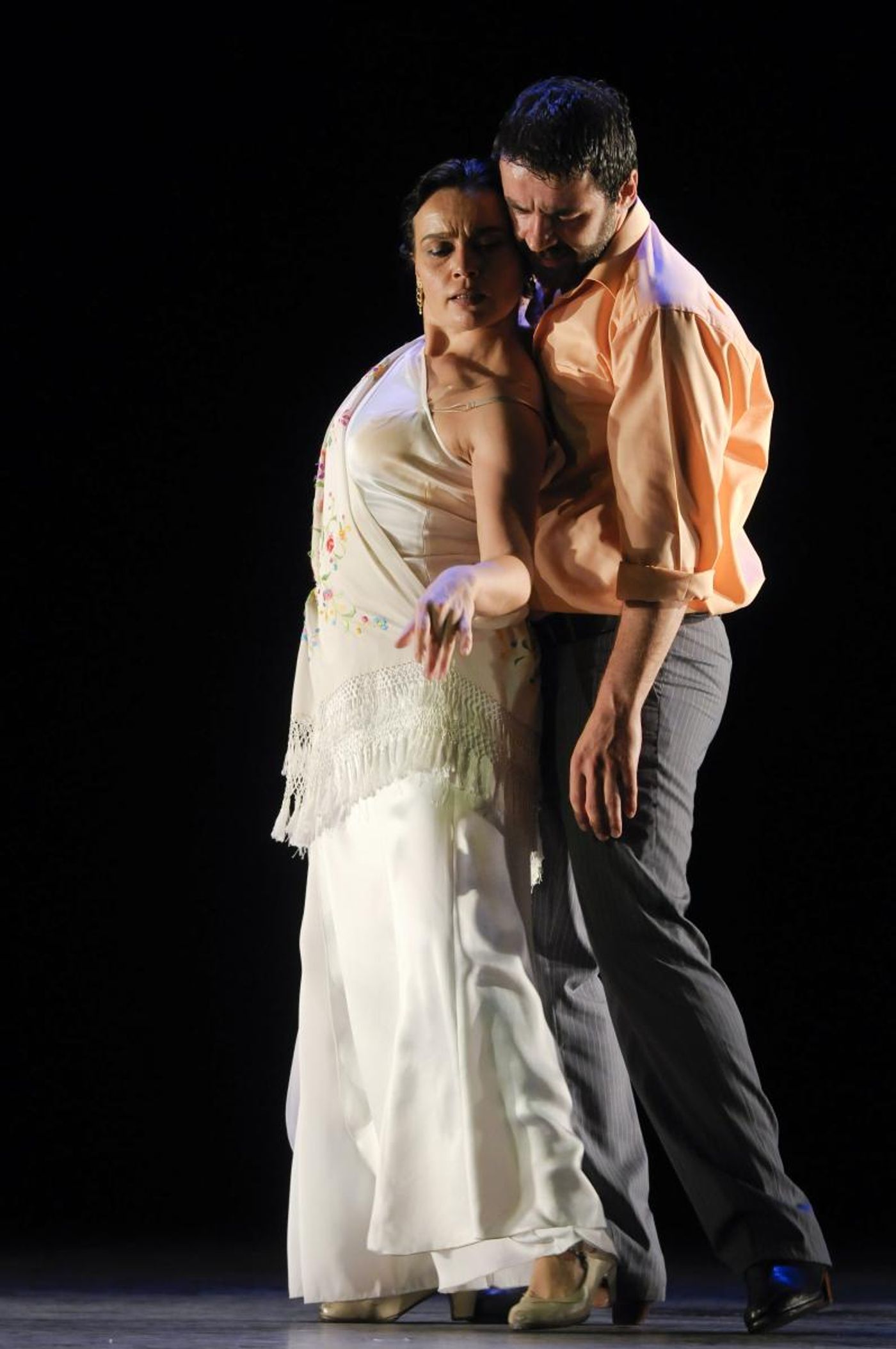

(photo provided by the subject)

Following on the rousing success of Antigona, their acclaimed and wildly popular flamenco adaptation of Sophocles' Antigone, Noche Flamenca returns to San Francisco's Z Space with their latest program Entre Tú y Yo (You and I). Conceived, choreographed, and directed by Noche Flamenca Artistic Director Martín Santangelo and lead dancer Soledad Barrio, Entre Tú y Yo explores through dance, music, and song the possibilities afforded and constraints imposed by relationships.

BroadwayWorld recently caught up with director/choreographer Martín Santangelo, who also just happens to be married to Ms. Barrio. A legendary dancer known for the drama and ferocity of her movements, Barrio has been called the "crown jewel of flamenco" by Dance Magazine and "a force of nature" by The New York Times. Santangelo himself also has a rich history as a dancer, including performing on Broadway in Julie Taymor and Elliot Goldenthal's Juan Darien. In conversation, he is incredibly articulate and passionate about Flamenco as a form of theater. Barrio had planned to join her husband for the interview, but was sadly called away at the last minute due to the serious illness of a family member. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

(photo by Andres D'Elia)

Tell me about Entre Tú y Yo. How would you describe the show? What do you hope audiences will take away from it?

First off, no matter what kind of show I'm doing, whether it be a narrative or a regular - whatever that means - a regular Flamenco show, one essential element is catharsis, a release of emotion that helps us continue with our lives. That's built into the Flamenco, and that's built into this show. That's the main thing that I try to adhere to because that's what the Flamenco, it's function, is - to allow a release of emotion so that we are somewhat relieved of our emotional states and more conscious the next morning of life, and able to go on. Because everybody's got their tragedies that occur.

Specifically for this show, for the last 3 years, I've been playing with the structure of Arthur Schnitzler's La Ronde. I fell in love with the film when I was about 19 years old, the Comedie Francaise version. It's extraordinary, the use of the mirrors is just over the top, the whole voyeur experience is incredible, and then something did stay true to the theatrical version, which is the structure, so simple but so genius. The audience is allowed to become a witness to an occurrence, whether it be perverse sex or subversive sex, or intimate moments between a couple. I first tried to do the actual play at Joe's Pub, which was a trip, because it's a small nightclub with a tiny stage. And I just broke the envelope and did as many theatrical tricks as I could to remain true to the play. It worked very well, but then I realized what I had done is something that I have been trying to get to for a while.

The thing about the Flamenco is we see dancers and singers and guitarists continuously breaking the fourth wall, and it's somewhat imposing on the audience. The Flamenco is such an attractive art form that we get away with it. There's a sense for me that we overwhelm the audience, and we underwhelm the experience of the communication that can happen internally within the Flamenco, within the artists onstage. What blew my mind was this Schnitzler structure removed all of that, because it was 2 people playing off of each other. And I went through every combination in the last 3 years - a guitarist and a dancer, or a singer and a singer, or a percussionist and a singer. And they have a scene that has a beginning and a middle and an end, there's a conflict and a resolution. What I've found from audience members is that they say "Thank you because we're allowed to witness something instead of being imposed by something." Because the effect is quite different. What's so extraordinary about Schnitzler's play is that he found a structure that led to a voyeur experience. I don't know if it was accidental or not, but he got to something technically and narrative-wise that I'm hangin' onto.

Entre Tú y Yo is inspired by the play, but it's not adhering to the complete narrative. There are three or four scenes about unrequited love and clandestine relationships that occur onstage. There are other scenes not specifically about that, but they do adhere to two or three people maximum on the stage playing off of each other. It's led me to a new structure of placing Flamenco on the stage, which is much truer to what Flamenco is than what we usually present. Usually we're breaking the fourth wall and a dancer is almost saying to the audience, "Look at me, look at me, look at me!" and playing off of that. We play off of the audience, and that's fun and all that, but it destroys the communal relationship between the artists in Flamenco. Which is really important, because if that exists then the cathartic element in Flamenco occurs. And so I found a structure that allows me to speak more truthfully about why Flamenco exists. It doesn't exist because it's a form of entertainment. It exists because people were persecuted - economically, culturally, religiously - and they screamed out. And their form of screaming out was getting together and finding a musical form to be able to scream out to each other, and then they could get up the next morning and go on with their lives.

(photo by Zarmik Moqtedari)

I've seen a quote from you that "the most essential thing is to really be able to witness the essence of a person doing the Flamenco because that's when you really see something." I'm fascinated by that idea of communication onstage and how performers keep it alive for every performance and not just fall into a rote pattern of, "Well, the dancer does this so then the guitarist does that." How do they keep it in the moment?

Over the years I've found different techniques. Sometimes I talk to a singer before the show and say, "Hey, change this up." But we don't talk to anyone else. And they say, "How?" and we talk about how, tonality-wise and rhythmically. The proposition is change. They change it and then the other artists onstage have to change. They have no other recourse - they have to be in the moment. If I talk to a guitarist and he changes up what he's doing, the singer and the dancer and the percussionist have to change what they're doing. This keeps them on their toes and in absolute communication. They're obliged to communicate then and there, and in doing so they find a way back to our structure that we've rehearsed.

That's one technique I've found to keep them alive and to keep the communication real. Because it is so easy in the Flamenco to wow people. You know, you get a guy with tight pants and on, looking good, and he's doing all that footwork and people are like, "Omigod! They can do that?!" And we get infected by that and we do more and more of that, and then all of the sudden we lose why we really started doing Flamenco. So it's utterly important for me to find any way, any technique that I can conjure, to force them to have real communication onstage and not to repeat.

This next question I had intended to ask Soledad. I haven't yet had the pleasure of seeing her perform live, but watching videos of her I'm struck by how she seems as though she's just making up the movement as she feels the music in her body. Is that what's really going on? How much of the movement is strictly choreographed, and how much is improvised?

With Sole and the other artists, especially in a solo, we work first with musicians to find point A, point B, point C, point D, [etc.]. And they're very specific points that we have to hit.

And as an audience member, I'm not going to necessarily notice them, right?

Probably not. You might notice them - some of them are big stops, some are rhythmical changes, some are when the singer comes in. But then, if I can really, really define the structure in a very clear way musically, I bring the dancers and the singers in and say, "This is the structure. This is what you're gonna hit." And then we find different ways - the journey from A to B changes, but they have to get to B, they can't skip B, or C or D. They can't change that order, but the journey, the adventure, from A to B is not defined. They know where they're going; they don't know how they're going to get there. You know, it's like you have to go from Philly to Chicago to San Francisco. OK, but who am I going to sit next to and what's the conversation going to be?

Sole, if you see her solo which she's going to do in San Francisco, she's done it probably six or seven hundred times. The musicians and singers are always on edge because we're never sure when and where it's going to change. We always hit the structure - points A, B, C, D - we always hit them, but it always is changing. So the communal experience [occurs, which is] so important in the Flamenco. If a singer decides to sing two songs instead of one, back-to-back, and in rehearsal it's just [been] one song, then the guitarist and the dancer have to accompany that song, so they are making up things in the moment. There's this wonderful back and forth communication that they have to rely on each other. And what happens is they have more amplitude of expression, and are freer to express how they feel that night. They may be very happy, they may be very sad. Like Sole's [family member] may die and she has to do the solo, and if she feels that, she looks at the singer and she does a move saying "Sing another song because I want to lament about this." The singer will sing another song, the guitarists have to play it, she has to dance it, and we don't know the choreography. So, yes, there's all those delicious things about being able to pour your feelings in - which is a technique, a very tight technique - but that you can put your feelings into it, and then it stays alive; it's not repetitive. That's a long-winded answer, I'm sorry! [laughs]

(photo by Andres D'Elia)

I wanted to go back to the beginning of your partnership. How did the two of you first meet?

I was in Seville for two years then I went to Madrid, and I wanted to take a class with one professor, and I asked him if I could watch the class. And I saw this woman doing devolees on diagonal across the floor in the class and my mouth hit the floor. I was thunderstruck by this woman, Sole. She was in a relationship and I did something quite subversive - Arthur Schnitzler woulda loved it! [laughs ] - I did everything I could to become friends with her then boyfriend to guarantee me some kind of proximity to Sole. Her relationship to him lasted a few months, and I fell deeply in love with her. I was attracted to her from seeing her dance. She's so corporeally expressive, and so very deep and sincere about her movements that you just get super attracted to her. She has a tremendous amount of technique, but she's always looking for truth of movement. If she lifts an arm up, she really, really spends a long time discovering why the arm moves up, where it comes from and how it should move up. There's no artifice in her movement, and that's what really blew my mind. So I wooed her [for] about eight months - but I was successful and we fell very much in love.

Since we're doing this interview for BroadwayWorld, I have to ask you about performing on Broadway in Juan Darien at Lincoln Center. Any special memories from that experience?

Oh, god, yeah - many memories. It was wonderful to be directed by Julie Taymor. She's very specific about what she wants. I would come in with different things in choreography and - without knowing the Flamenco - she would say "That I don't want, that I want, that I don't want." It was a luxury because she was not in the Flamenco world, but she took the time to understand the vocabulary of the Flamenco, what specifically it expresses, and she chose and edited those expressions. It was a very rich way of working with somebody who wasn't a "choreographer" but was working on choreography - you know, editing. That was an eye-opener for me, another way to work.

And then I was in a gigantic, gigantic mask. That was a whole different trip - how to do mask work in Flamenco. I learned a good amount about mask work and how to express [emotion] - because the face is a big thing in the Flamenco, people look at your face constantly. This was a static mask, and she worked with me a lot because she's a master with mask technique. If you move your face an inch to the right, what occurs with the expression of this static mask? Oh, it expresses this, or it expresses that! So I learned a tremendous amount about mask work, which was fantastic for me.

That's so interesting. I've never really understood the complexities of mask work, but the way you just explained it makes a lot of sense. Like, I'll think "Wow, this performer has an expression they didn't have just two seconds ago, but their mask hasn't changed. How do they do that?"

Yeah, it's extraordinary and it's all about the technique. She knows it, she studied mask work from Indonesian masks, Indonesian puppets to Butoh to Noh. She's studied a tremendous amount about masks and movement, which is one of her fortes. So - I learned a lot from Julie Taymor.

And since your publication is a theatrical publication, I do want to say that in the last eight years I have realized that what we're doing is theater. I think I've been lucky to be obsessed by theater, especially by playwrights and stories. It's so much richer when dance is either telling a story or inspired by a story because then it becomes specific about what we're doing onstage. My love affair with La Ronde has helped me so much with dance, with music. It doesn't become flagrant, what I do, because I'm more and more adhering to a narrative to tell a story, at the very least an emotional story if not a specific narrative. I'm in love with theater as dramaturgical work, I'm absolutely bitten and in love with it. And Sole's just so damned extraordinary. She's an actor, she's a tremendous actor.

One final question I assume you get asked a lot: You and Sole are married to each other and work so closely together. How do you manage that without driving each other crazy?

[laughs uproariously] I don't get asked that a lot, but that's a great question! The way that we manage is that we live together and have a family and all that stuff, right? But then the artistic part is the relieving part. Because there we're not dad and mom, we're not husband and wife, we're not the couple living at home together. We're two artists trying to get to something together. We know each other well, which helps, and I have a very different role than she does. There's a quote, something about "I talk, she listens. She dances and I watch." Something like that. And it's so true because we really try to get at something together, but from very different roles. That's the relieving part, and that's why honestly, I love working with Sole. I think a big part of it is because if I didn't work with Sole, as an artist, as a director, choreographer, I think I would go nuts. I think we would drive each other absolutely crazy. You know, the typical thing about husband and wife. "I'm fed up with you!" and "I'm fed up with you!" and it becomes repetitive and dry and this and that. I think what saves us is the work, and our respective roles in the work.

Entre Tú y Yo runs from Thursday, October 31 through Saturday, November 16, 2019 at Z Space, 450 Florida Street, San Francisco. Tickets and information can be found at zspace.org or by phone at 415-626-0453.

Videos