Review: SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY PREMIERES A NEW WORK BY BILLY CHILDS at Jacobs Music Center

Pianist Alexander Malofeev Excites with a Prokofiev Concerto

Alexander Malofeev was 13 when he won the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Competition for Young Musicians under 18. His technical prowess was exceptional, but his musicality at such a young age was what convincingly set him apart. Now 23, he has lived up to expectations, garnering rave reviews for performances with major orchestras around the world.

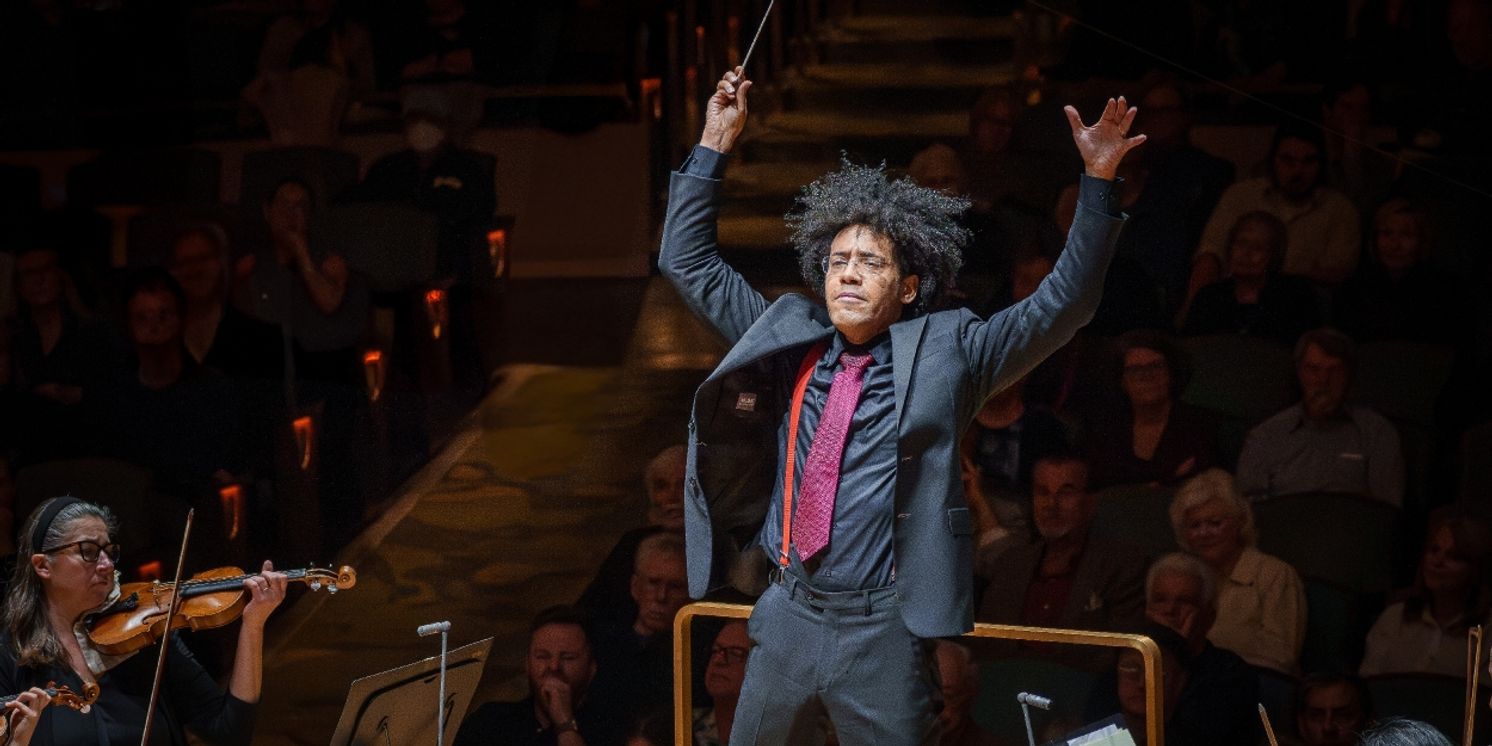

Nor did he disappoint on this evening with Prokofiev’s 3rd piano concerto, but I’ll start with the most familiar work on the program, Beethoven’s 3rd symphony, the “Eroica.” It was the only work after intermission, and conductor Rafael Payare led without a score.

Since the symphony is so often performed and recorded, it’s almost always a mistake for a conductor to try to reveal something new by exaggerating speeds, changing crescendos or lingering on the more beautiful passages. Payare let the music speak for itself, rather like an old friend you listen to and appreciate more each time you do.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Balances, tempos and dynamics were well-managed. It was a clean performance with precise entries, warm strings, flawless woodwind and brass solos, and timely percussion exclamation points.

Continuing the program in reverse order, before intermission Malofeev and the orchestra delivered a blazingly fast, exciting version of Prokofiev’s most popular piano concerto, his third. Like Malofeev, Prokofiev was himself a prodigy. In his case, as both pianist and composer, having written a short piece for piano at five and his first opera at nine. (It’s not expected to premiere at the Met anytime soon, but still.)

Prokofiev was the pianist when his 3rd concerto premiered in Chicago. Before the performance, he wrote to conductor Serge Koussevitzky, “My Third Concerto has turned out to be devilishly difficult. I’m nervous, and I’m practicing hard, three hours a day.”

He toured successfully with the piece for 10 years and recorded it as well. Malofeev hasn’t played it as often as the composer did, but it has become one of his specialties. Tempos made no concession to the work’s many technical difficulties that include long double-note arpeggios that even professionals debate how to finger.

It was a commanding performance, matching many of the best recordings, though not quite Martha Argerich’s deliriously whirling frenzy in the concluding crescendo. Try this on YouTube with Andre Previn conducting. Skip to the final two minutes of blurred finger work whenever you need a charge.

After three curtain calls, Malofeev played "Canzona Serenata" from Nikolai Medtner's Forgotten Melodies, Russian in its melody and a lovely romantic contrast with the concerto.

At last, I come to the first work on the program, the world premiere of Billy Child’s Concerto for Orchestra commissioned by San Diego Symphony.

In his informative preconcert lecture, Alex Greenbaum, cellist of the Hausmann Quartet, told the audience that the orchestra had first rehearsed Childs’ new piece three days before the first performance. I wouldn’t have guessed that.

Under Payare’s baton the piece came to life, and the musicians responded by playing with precision and tonal excellence, impressively so for a new work with diverse melodic and rhythmic demands.

Contemporary composers have gradually, at times it seems reluctantly, returned to music audiences more readily understand, enjoy and accept. Several, most notably John Williams, have first become known through their work in films. The highly successful Mason Bates continues to work as a DJ in electronic dance clubs.

Billy Childs, in addition to composing, performs and records as a pianist, typically leading his own small jazz group. He has accumulated seventeen Grammy nominations and won six times, twice for Best Instrumental Composition. In recent years, like trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, Childs has spent more time on his classical compositions and has received more than a dozen commissions for chamber and orchestral works.

San Diego Symphony was one of nine orchestras that commissioned his recent (2022) Diaspora: Concerto for Saxophone, and the Symphony commissioned his Concerto for Orchestra, which was premiered on this program.

When I said that composers have “gradually … returned to music audiences more readily understand,” this concerto for orchestra is an example of what I had in mind as more approachable than much of the new classical music of the late 20th and early 21st-Centuries.

In its two contrasting movements, it is colorful and largely tonal, but still, for many listeners, missing the appeal of the melodies, rhythms and structures that made the reputations of Beethoven and Prokofiev.

Childs is more concerned with textures and changing moods. Snatches of melody move through section ensembles and soloists. As is expected in a concerto for orchestra, the work is designed to show off the differing strengths of strings, brass, woodwinds and percussion.

Individual solos too were designed to take advantage of the unique strengths of their instruments. A clarinet opens the piece with soft liquid grace in the calmer first section, and a bold horn has the spotlight as the livelier second section approaches a rousing conclusion with full orchestra, brass at the top.

Have classical composers, partly under the influence of what satisfies movie goers, gamers and jazz and rock fans, found a way to significant growth in their audience? I’m not convinced but hesitate to judge.

Many early critics and audiences found both Beethoven’s “Eroica” and Prokofiev’s 3rd piano concerto incomprehensible, even unpleasantly savage uses of an orchestra. Will Childs, Bates, or Marsalis’s classical music influenced by other genres be remembered a century from now?

As a final note, Martha Gilmer announced that violinist Hernan Constantino was retiring after 30 years with the orchestra. That brought applause in his honor from the audience and, with much stomping of feet and firm tapping of bows on music stands, even greater enthusiasm and grins from his fellow musicians. I was reminded of the esprit de corps of a successful sports team.

The scene was repeated at concert’s end when Payare rushed to shake Constantino’s hand and deliver a colorful cluster of flowers to the smiling violinist. In addition to his work with the symphony, he has been a teacher and conductor, currently of one of the Mainly Mozart youth orchestras.

Photos by Gary Payne, compliments of San Diego Symphony.

For schedules of the remaining concerts in this season and planned for next, visit the San Diego Symphony website.

Reader Reviews

Videos