Review: UC San Diego Honors The Music And Influence Of Chou Wen-chung at the Conrad Prebys Music Center

Composer Chou Wen-chung, who died recently at the age of 96, was honored at the most recent "red fish blue fish" percussion concert. Chou's works have been performed by major orchestras throughout the world, and he mentored many who have gone on to successful careers of their own. Tan Dun and Chen Yi are among his best known students. Tan once called him "the godfather of Chinese contemporary music."

Composer Chou Wen-chung, who died recently at the age of 96, was honored at the most recent "red fish blue fish" percussion concert. Chou's works have been performed by major orchestras throughout the world, and he mentored many who have gone on to successful careers of their own. Tan Dun and Chen Yi are among his best known students. Tan once called him "the godfather of Chinese contemporary music."

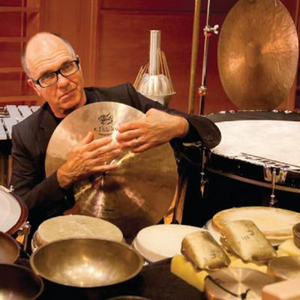

Steven Schick founded "red fish blue fish" and remains its artistic director and conductor. The group, made up of University of California, San Diego grad students, performs on the UCSD campus and travels for concerts across the United States and abroad. Schick is Distinguished Professor of Music at the university. An extraordinary percussionist, he has served as artistic director of the Swiss Centre International de Percussion de Genève, was the percussionist for New York's Bang on a Can All-Stars for a decade and is a Consulting Artist in Percussion at the Manhattan School of Music. He was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society's Hall of Fame in 2014.

Pulitzer-Prize composer Roger Reynolds began the evening with a heartfelt description of Chou Wen-Chung's influence on himself and other modern composers. That set the stage for the performance of Chou's Echoes from the Gorge, a piece for percussion quartet for which Schick was joined by James Beauton, Fiona Digney, and Garrett Mendelow. The quartet's array of percussion instruments included tiny bells, large gongs, bongos, a bass drum, an assortment of cymbals, wooden blocks, and more. At one point I counted 14 mallets, moving in such a blur I might have missed a few. As Schick tapped, stroked or hammered, subtle hand movements cued the other performers to ensure that complex cross-rhythms and often exotic coloring were executed cleanly. The percussion tour de force is divided into eleven brief segments with names such as "Drifting Clouds," and "Old Tree by the Cold Spring." Echoes from the Gorge was brought to a frenzied climax of light-speed mallets with "Falling Rocks and Flying Spray."

The program next turned to Chinary Ung and Lei Liang, UCSD professors who, like Tan

and Chen, had studied with Chou. Both have also won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award. Ung's composition Cinnabar Heart changed the mood from frantic to mellow. Rebecca Lloyd-Jones was her own accompanist in the piece for marimba and vocalist. Professor Ung, who happened to be sitting next to me, called her performance "elegant." I certainly agree and would add exquisitely beautiful.

Professor Liang composed Trans as a partly improvisatory solo for Steven Schick, with audience participation. This concert featured Liang's rearrangement for percussion quartet for which Schick was joined by Michael Jones, Rebecca Lloyd Jones and Matthew LeVeque. Audience participation remains part of the revised version. Upon entering the hall would-be performers were confronted with a box of stones out of which they could select two. As Schick raised his own two stones before beginning Trans, people realized their moment had come, and the sound of clacking stones filled the space. But the conductor, mildly impatient with the amateur stoneists, asked them to hold off while he explained their role. He then proceeded to show the stones could be played at different tempos, volumes, rhythms, timbres and pitches. That left out only harmony among the usually listed elements of music. I wouldn't be surprised if his next concert includes a concerto with the necessary four stones. But he might need a second skilled stoneist for triads.

Trans shows Chou's influence. It combines Western and Eastern musical traditions with an exciting variety of percussion instruments that produce a wide range of colors and moods. Chou often explicitly paints a musical description of nature. Liang sometimes does as well, but Trans leans more heavily to the abstract. He has suggested that the clacking audience is forming "sonic clouds." In any event, whether sounding like sonic clouds, crickets or just rocks, the audience enjoyed reacting to Schick's signals, and he has already given many performances of the work since he premiered it in New York in 2014.

Chou admired, was mentored by, and eventually collaborated with Edgard Varèse. Like Chou and Varèse, Michael Pisaro is fascinated by sounds and their ability to evoke emotions and memories. The second half of the concert began with Pisaro's ricefall, which was inspired by the haunting thoughts of author John M. Hull. In his memoir Touching the Rock Hull explains how oncoming blindness was changing the  way he listened. In one passage he describes the details he hears as he concentrates more than he ever had before on sounds and patterns as rain falls in a garden. By imitating those sounds in a concert hall, Pisaro hopes to attract similar intense concentration, and to see if he too could "hear" a landscape.

way he listened. In one passage he describes the details he hears as he concentrates more than he ever had before on sounds and patterns as rain falls in a garden. By imitating those sounds in a concert hall, Pisaro hopes to attract similar intense concentration, and to see if he too could "hear" a landscape.

The performance began with an intriguing scene--sixteen musicians sat on the stage in four rows, each with a ceramic bowl. Black on the outside and red within, the bowls were filled with rice. After a period of mysterious silence, the musicians raised fistfuls of rice they then let trickle down onto inverted pots, cardboard boxes, wood, and other surfaces. With my eyes closed, I could easily imagine I was listening to rain falling on shrubs, roads, and roofs. The performance was convincing. At 18 minutes the piece is too long, despite significant variations that range from drips to torrents. An expanded, ricefalI (2) adds three more 18-minute sections, sine tones and a few instruments. A recorded version includes a merger of 64 separate tracks of falling rice. It isn't on my Amazon wish list.

After Varèse's death, Chou and his wife moved into the famous composer's New York townhouse, and while the younger man continued to compose, he also completed several of Varese's unfinished works. Chou's close relationship with him demanded the program include one of Varèse's compositions. Since he is often called the father of electronic music, Poème Electronique was Schick's choice to complete the evening. Varèse's exploration of a zoo of electronically produced rings, growls, beeps, boops, and swoops was inventively outrageous in its time, but today seems at best whimsical.

Two musicians were at electronic panels and laptops to perform the piece. They, and each of the other concert's main performers showed why "red fish blue fish" has been a success, and why Schick can proudly state that all his percussion students have gone on to satisfying positions after graduation.

Photos compliments UCSD Music Department

This review is of a February 19th performance at the Conrad Prebys Music Center. For information about UCSD's extensive concert schedule visit the event calendar .

Reader Reviews

Videos