Review: PIPELINE at Portland Playhouse

Several years ago, I was at an art exhibit where one of the installations was a series of videos of young black men talking about what it was like for them to move about the world. It was the first time I realized how different our daily experiences are. As a white woman, I can walk down the street without having people think I'm a threat or report me for suspicious behavior. If I see a police officer, I know I can trust them to protect me. If I get angry, the worst thing people are likely to think is that I'm having a bad day.

Several years ago, I was at an art exhibit where one of the installations was a series of videos of young black men talking about what it was like for them to move about the world. It was the first time I realized how different our daily experiences are. As a white woman, I can walk down the street without having people think I'm a threat or report me for suspicious behavior. If I see a police officer, I know I can trust them to protect me. If I get angry, the worst thing people are likely to think is that I'm having a bad day.

This was not the experience of the men in the videos. They described walking down the street and seeing fear in people's eyes, of having people cross the street to avoid them, of seeing a policeman and feeling scared rather than safe. They were made to feel like monsters simply because of the color of their skin.

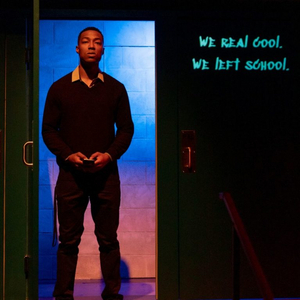

Dominique Morrisseau's PIPELINE, now running at Portland Playhouse in a co-production with Confrontation Theatre, examines the idea that our society doesn't give young black men space to move around in the world. Using Gwendolyn Brooks's poem "We Real Cool" as a framework, the play examines the consequences of treating people like monsters. The pipeline in the title refers to the school-to-prison pipeline that results from disciplinary policies that disproportionately affect black students.

The play opens with Nya, a high school teacher, calling her ex-husband about their son, Omari, who has had an incident at school. Omari doesn't attend Nya's school, which is in their neighborhood, but instead goes to a private school upstate. The incident happened in English class, during a discussion of Richard Wright's Native Son, where, as the only black student in the room, Omari was expected to have unique insight into why Bigger Thomas did what he did (if it's been awhile, here's the SparkNotes summary). A classroom exchange spiraled out of control, the incident was caught on cellphone cameras, and charges are being considered. Like Native Son, the play is not so much about the incident itself, but about why it happened -- Is Omari a monster? Or was he provoked into a monstrous action? What is the appropriate way for young black men to express rage? At the same time, it's a story of a mother trying to protect her son.

Directed by Damaris Webb, PIPELINE bursts onto the Portland Playhouse stage in a flash of light and sound, with music and videos playing as the characters walk out. The play demands attention. And it earns it. Anchored by Ramona Lisa Alexander as Nya and La' Tevin Alexander as Omari, this production is like a lightning bolt. At times, you might laugh, be shocked, be angry, or cry, but you'll have no choice but to be present, to see Omari for who he is -- not a monster, but a teenage kid with feelings he doesn't quite know what do to with.

The supporting cast is also fantastic, with especially powerful performances from Tyharra Cozier as Omari's girlfriend, Jasmine, and Alissa Jessup as Nya's colleague Laurie.

PIPELINE is a piercing, insightful play that gives voice and dimension to a demographic our society is too eager to write off. I recommend it very highly.

PIPELINE runs through March 15. More details and tickets here.

Reader Reviews

Videos