Review: Atlantis Theatrical Crafts A Polished Rendition of MILLENNIUM APPROACHES

Manila, Philippines--Acclaimed playwright Sarah Ruhl began her career as an avid consumer of other people's works. A church in Chicago was the unlikely venue of her first encounter with "Angels in America," where she gushed about Tony Kushner's work for its "seriousness, endurance, political engagement, and language."

Manila, Philippines--Acclaimed playwright Sarah Ruhl began her career as an avid consumer of other people's works. A church in Chicago was the unlikely venue of her first encounter with "Angels in America," where she gushed about Tony Kushner's work for its "seriousness, endurance, political engagement, and language."

Ruhl's epiphany was not uncommon. Critics far and wide hailed "Angels" as the most significant American drama of the 20th Century. Its Pulitzer Prize was sweet icing on the cake.

Classifying "Angels" as a genre is tricky. The realism is staunchly intimate (cozy enough for a church), but the scope is mythic as it dabbles in symbolic abstractions of the morality tradition. By turns exalted and profane, Kushner's language illustrates the chasm between national tragedy and social justice.

"Angels" draws its setting from the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Ronald Reagan's policies--an enormous boon to the neocons and the filthy rich--gave Kushner literary fuel to resist a harsh ideological current. To Kushner, Reagan's arrival fomented a class war and threatened to poison American politics for years to come. (He'd already written another play - "A Bright Room Called Day," a blistering polemic against Nazism in which a Brechtian narrator compares Adolf Hitler to Ronald Reagan.)

"Millennium Approaches" is the first title of a sprawling two-part series ("Perestroika" is the second part, which is not on this year's calendar). It opens the 20th-anniversary season of Atlantis Theatrical Entertainment Group, arguably the country's flagship producer of Broadway musicals.

Indeed we had grown enamored of the company's rousing musical productions, so it was fair to be skeptical about its effort to open the season with a straight drama. Be that as it may, Atlantis earns the ovation for ushering its milestone with no less than a robust discourse on the culture of illness and political outrage.

Director Bobby Garcia helmed the entire series over two decades ago. This time around, with "Millennium Approaches," he responds to a familiar sense of urgency: the AIDS epidemic in the Philippines hits a critical stage, as the cure gets more elusive in light of a blinkered public attitude.

Atlantis has piqued our interest by touting a who's who of veterans to execute Kushner's demanding roles. Because of that promise, we're right to expect nothing less than the same hard-hitting outcome that floored Ruhl many years ago.

On that account, Garcia has a chance to showcase a spellbinding revival. But he's up against the limitations of time and budget--a common business reality, is all. In the ideal world, Garcia could use a couple more weeks of preview performances to assess and tweak a production of this magnitude. (Smaller theater companies have the leisure of a more extensive rehearsal schedule.) His actors are undoubtedly solid, but they too could use the additional opportunity to sculpt a muscular dialogue needing shape and definition.

On that account, Garcia has a chance to showcase a spellbinding revival. But he's up against the limitations of time and budget--a common business reality, is all. In the ideal world, Garcia could use a couple more weeks of preview performances to assess and tweak a production of this magnitude. (Smaller theater companies have the leisure of a more extensive rehearsal schedule.) His actors are undoubtedly solid, but they too could use the additional opportunity to sculpt a muscular dialogue needing shape and definition.

In the playwright's world, the "threshold of revelation" requires that the shell of understanding be cracked open. Garcia's ensemble has merely begun to scratch the surface; hence, the characters are missing the highest stakes to justify their lowest conditions. (Strong individual performances don't necessarily translate into meaningful relationships.)

What's It All About, Kushner?

We'll get to the notable performance and production details, but a small piece of dramaturgy should clarify the landscape for first-time viewers.

Kushner exposes the dissolution of a modern relationship, exemplified by two young couples in crisis: Prior Walter and his lover, Louis Ironson; and Mormons Joe Pitt and his wife, Harper. Prior has contracted the AIDS virus, setting Louis into panic out of fear for his own life. Joe is a closeted homosexual, and Harper is agoraphobic and addicted to Valium. When Joe gets an offer for a dream job in Washington, Harper's anxiety exacerbates at the thought of relocating to a new city.

A twist of fate finds both couples crossing each other's paths. Joe meets Louis in the men's restroom of a courthouse where they both work, and Prior meets Harper in a bizarre, shared dream in which he reveals that Joe is a "homo." Joe denies it to Harper but hints at an "inner struggle." (In the eyes of God, he is doing his best to be a good man, so what does it matter how he truly feels?). Eventually, Louis leaves Prior to be with Joe, and Harper leaves Joe to find herself. Prior hits rock bottom before he encounters the angel.

A twist of fate finds both couples crossing each other's paths. Joe meets Louis in the men's restroom of a courthouse where they both work, and Prior meets Harper in a bizarre, shared dream in which he reveals that Joe is a "homo." Joe denies it to Harper but hints at an "inner struggle." (In the eyes of God, he is doing his best to be a good man, so what does it matter how he truly feels?). Eventually, Louis leaves Prior to be with Joe, and Harper leaves Joe to find herself. Prior hits rock bottom before he encounters the angel.

It's a good premise for a modern tragedy, but Kushner pursues an elaborate detour by trafficking in cosmology and trotting out sequences from altered states of consciousness. He sends ghosts of Jewish ancestors in the Dickensian mold and appropriates a hermaphrodite for a seraph with a flair for dramatic entrance (read: crashing through the roof of a sick man's apartment).

In a sly spin, fiction meets real-life villain Roy Cohn, a closeted troglodyte and right-wing bully who gets his savage retribution by dying of the same affliction he had callously branded as a homosexual disease. His passing would prove to be insufficient solace to a nation reeling from his political abominations. (Cohn once served as chief counsel for Senator Joe McCarthy, and later as a legal fixer and mentor to a young Donald Trump, no doubt leaving his mark on a "conservative" culture that has since transmogrified into the hideous version of America we know today).

Casting Call: The Great Work Begins

Prior Walter is the classic everyman with a spine-chilling grit that marks one of Kushner's central themes. The character requires strong physical stamina and mental acuity to sustain the illusion of incontinence and decay. Prior is a spiritual warrior with a keen sense of humor.

To that end, Topper Fabregas fits the bill: a vulnerable and intuitive actor attuned to the demands of Prior's deteriorating faculties. Fabregas has yet to fully embrace Prior's inquiry into an authentic spiritual awakening, as opposed to mere hallucinations resulting from his debilitating disease. The angel is terrifying, but she's also benevolent. Prior can afford to integrate their divine love affair earlier in his narrative.

To that end, Topper Fabregas fits the bill: a vulnerable and intuitive actor attuned to the demands of Prior's deteriorating faculties. Fabregas has yet to fully embrace Prior's inquiry into an authentic spiritual awakening, as opposed to mere hallucinations resulting from his debilitating disease. The angel is terrifying, but she's also benevolent. Prior can afford to integrate their divine love affair earlier in his narrative.

(Fabregas played another gay man who dies of AIDS in a production of "The Normal Heart" a few years back. Since then he has gained immeasurable acting maturity, as his Prior takes a deeper plunge into that horrific, sacred place where transformation occurs.)

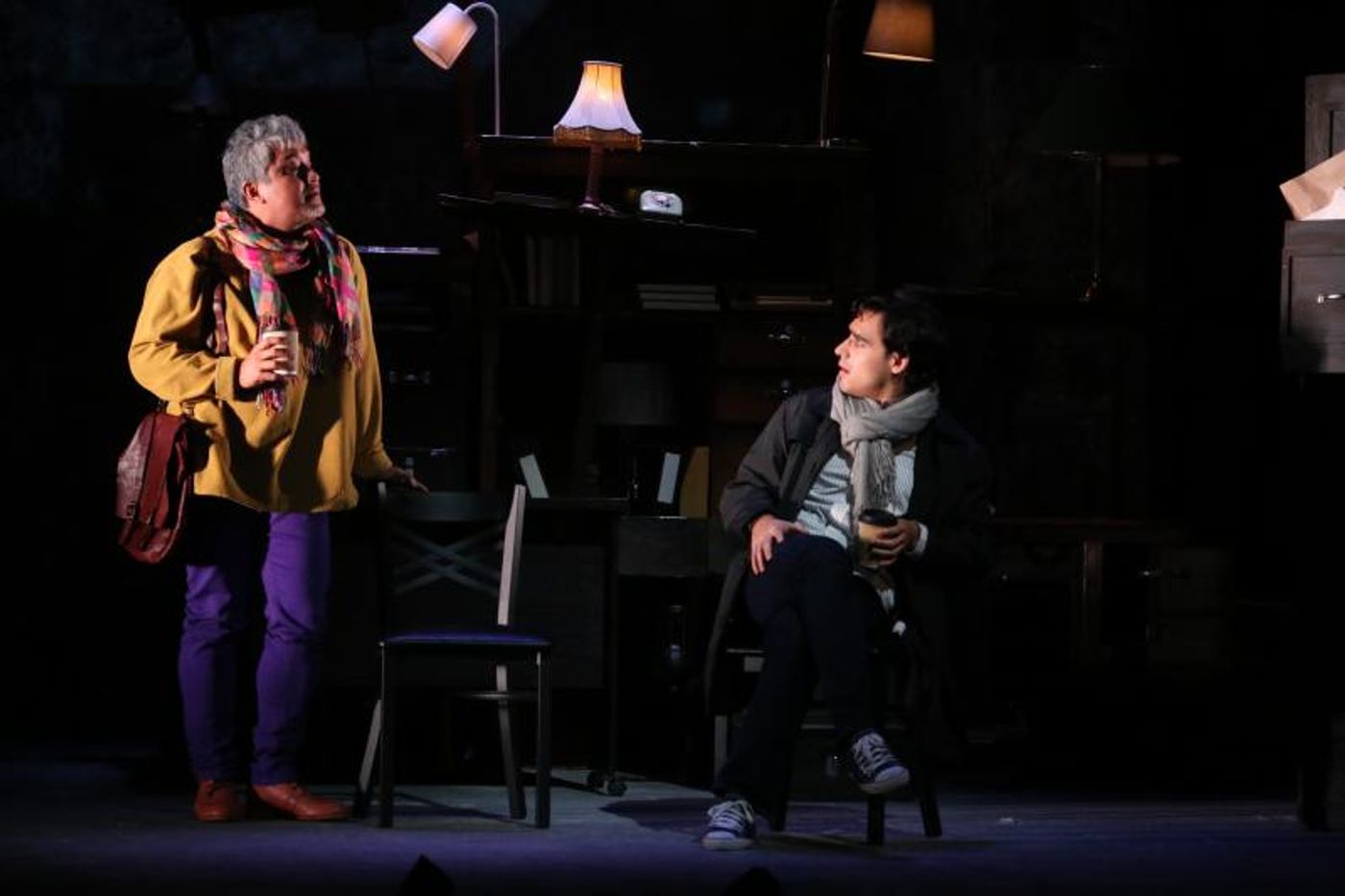

Nelsito Gomez is Louis Ironson, a verbose neurotic who is overcome by a rational fear of death. His love for prior is believable, and so is the self-loathing that results from his betrayal of Prior. (There's widespread agreement that Louis is Kushner's stand-in, his mouthpiece for breaking down the monolithic "angry white male.") That said, his fear isn't enough to elicit our sympathy. We await Gomez's utter emotional destruction borne of Louis' dangerous behavior.

Markki Stroem is a fabulous Joe Pitt, a devout Mormon lawyer caught in the painful struggle of sexual repression. His wife Harper is an amiable model of dependency who surprises us with a firm resolve to initiate the end of her marriage. Angeli Bayani essays a tender and stubborn Harper Pitt (her fierce confrontation with Joe's secrets is heartbreaking), but we expect to see a more precise distinction of her elevated, albeit drug-induced, moments of well-being.

Trained as a theater actor with a solid New York pedigree, Art Acuña returns to the stage after a hectic film and television schedule. His Roy Cohn is stoic, sleazy, and powerful. But we get the sense Acuña could turn Cohn's malevolence up a notch. He seems to hold back, presumably a by-product of his restrained refinement on the screen. But he's Roy Cohn, after all; he is bigger than life and he owns the damn stage. Case in point (and Garcia may have considerable input here), a pivotal scene in Act 2: Cohn delivers a ferocious ultimatum for Joe to take the job, but he stays glued to his seat like a dog to his bone, restricted behind an oversized table, undermining what is arguably his peak moment up to that point. (There's a lot of sitting going on throughout the play.) From our vantage point, a silent Joe wields more power in this scene than an impassioned Roy due to questionable actor placement and a composition lacking in tension.

Trained as a theater actor with a solid New York pedigree, Art Acuña returns to the stage after a hectic film and television schedule. His Roy Cohn is stoic, sleazy, and powerful. But we get the sense Acuña could turn Cohn's malevolence up a notch. He seems to hold back, presumably a by-product of his restrained refinement on the screen. But he's Roy Cohn, after all; he is bigger than life and he owns the damn stage. Case in point (and Garcia may have considerable input here), a pivotal scene in Act 2: Cohn delivers a ferocious ultimatum for Joe to take the job, but he stays glued to his seat like a dog to his bone, restricted behind an oversized table, undermining what is arguably his peak moment up to that point. (There's a lot of sitting going on throughout the play.) From our vantage point, a silent Joe wields more power in this scene than an impassioned Roy due to questionable actor placement and a composition lacking in tension.

By contrast, Cohn's rare show of humanity pierces through during his agonizing decline in Act 3, thanks to Acuña's massive range and intensity.

Pinky Amador, another dependable royalty in the business, plays the angel and doubles as Prior's nurse, along with two other supporting characters (Kushner's requirement of all his actors). Amador's Angel is gorgeous and imposing, but in Sunday's performance, Amador seemed uncomfortable in harness--or is it fear of heights? Stunning optics, but where's the magnificent wonder?

Andoy Ranay is a sensitive and grounded Belize, a former drag queen and Prior's best friend. He's no pushover and holds his own in protecting Prior from Louis' destructive energy. Ranay also plays the avuncular imaginary friend and tour guide in Harper's hallucinations.

Andoy Ranay is a sensitive and grounded Belize, a former drag queen and Prior's best friend. He's no pushover and holds his own in protecting Prior from Louis' destructive energy. Ranay also plays the avuncular imaginary friend and tour guide in Harper's hallucinations.

Last but certainly not least is Cherie Gil's versatile performance in multiple roles. She opens the show as an orthodox male rabbi officiating a funeral, plays an erudite doctor who diagnoses Roy's illness, transitions into Prior's conservative mother, Hannah Pitt, and returns from the dead as Ethel Rosenberg to gloat over a dying Roy. In each depiction, Gil exhibits an impressive range that includes a nifty command of vocal varieties. She turns in the most nuanced achievement.

Production Blues

Finally, I'd be remiss to ignore a cumbersome element that delineates the scenic composition of this production. If Faust Peneyra's multi-level set design is supposed to simplify our perception of Kushner's transient realities, the permanent wooden structure on either side of the stage fails to do so.

We get Kushner's preference for seamless movement between scenes, and we can see how Peneyra's design works to the specification as we shift our attention from, say, office space to one's bedroom. But here lies the problem: the dead weight is a pompous literal construction that signifies stasis and defeats Kushner's idea of  mobility. Man's addiction to movement is, in fact, the supposed singular defect that necessitates divine intervention. During scene changes, the motionless fixture doesn't serve anyone except perhaps to create additional masking for the actors upstage. Besides, that interior construction requires a vast stretch of the mind to imagine Louis' sex scene with a Central Park stranger--as it happens near a visible file cabinet with Harper's lampshade on it. (It isn't entirely Peneyra's call; that scene could have taken place elsewhere.)

mobility. Man's addiction to movement is, in fact, the supposed singular defect that necessitates divine intervention. During scene changes, the motionless fixture doesn't serve anyone except perhaps to create additional masking for the actors upstage. Besides, that interior construction requires a vast stretch of the mind to imagine Louis' sex scene with a Central Park stranger--as it happens near a visible file cabinet with Harper's lampshade on it. (It isn't entirely Peneyra's call; that scene could have taken place elsewhere.)

We have GA Fallarme to thank for his evocative projections to clarify locale. Jonjon Villareal's lighting is stark minimalism. It's affecting, but we could do without the repeated blackouts that do little to sustain momentum. For enhanced mood, the original music score and sound design inspire an effective otherworldly immersion. Those credits belong to Louise Ybañez-Javier and Glendfford Malimban, respectively.

In the end, Atlantis has crafted a polished and antiseptic rendition of "Millennium Approaches" where the unwashed squalor of human suffering might have done us in. Frankly, we are excited for "Perestroika," if only to allow the company's potent seeds the time and space to emerge and reach full bloom.

"Angels in America: Millennium Approaches" plays at Carlos P. Romulo Auditorium, RCBC Plaza, Makati City, now through April 7, 2019. Get tickets (P1,500-P3,500) at TicketWorld.com.ph.

Photos: Jaime Unson, Atlantis Theatrical Entertainment Group

Reader Reviews

Videos